“As we move further into science and further into AI,” says Stephen Schwarzman, “there are still going to be human beings around” – which will come as a relief to all concerned. “I thought I should do something to reaffirm the importance of the human being,” he adds. That something was a donation of £185m to Oxford University, the largest in its history, to fund the biggest single building that it has ever erected in one go: the 25,300 sq metre (272,000 sq ft) Stephen A Schwarzman Centre for the Humanities.

This building, whose cost is undisclosed, houses nine faculties and institutes that range from the ancient subjects of philosophy and music, as well as English, history and languages, to the new Institute for Ethics in AI. It additionally includes, at the donor’s insistence, performance venues and galleries where a public cultural programme linked to the work of the faculties can be put on show.

Schwarzman – who is the chair, chief executive and co-founder of the US private equity group Blackstone, and is said to be worth about $50bn – is speaking to camera in a digital briefing on the just completed endeavour. He stresses its ancient and modern theme: “It’s very satisfying to play a part in the future and to be part of the elegance and beauty of the past.” A portion of the brief for the project was that it should be a contemporary version of a traditional Oxford building, and so its highly engineered fabric is wrapped in an exterior of Clipsham stone, the material from which much of the city was built. Its style is also an updated and abstracted version of classical architecture.

The facade of the Stephen A Schwarzman Centre, wrapped in traditional Clipsham stone

The building is designed by Hopkins Architects – a practice with a knack for being tech and trad at the same time – whose founders Patty and the late Michael Hopkins made their name in the 1970s with a radical but refined house for their own use in Hampstead, north London, in skinny metal and glass. Later, with the Mound Stand at Lord’s cricket ground and the rebuilding of Glyndebourne opera house, they found ways to combine modern materials and techniques with stone, brick and timber. With Portcullis House, the office building for MPs next to the Houses of Parliament, Hopkins invented a millennial Tudor style out of bronze, stone and air ducts.

The new centre for the humanities stands in the four hectare (10-acre) Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, a campus created on the site of a former hospital that now includes the Mathematical Institute and the Blavatnik School of Government, respectively designed by the late Rafael Viñoly (of Walkie-Talkie skyscraper fame) and Herzog & de Meuron (Beijing Olympic stadium, Tate Modern). Student accommodation for Somerville College by the Stirling prize winner Niall McLaughlin stands to one side. The place is a stamping ground for big donors and famous architects that is not yet more than the sum of its parts, with big statements in curved glass and gridded concrete shouting at each other across some rather shapeless open spaces.

The idea is to create the opposite of the introspection of Oxford buildings and the inviolate college quads

The idea is to create the opposite of the introspection of Oxford buildings and the inviolate college quads

In this context, the Hopkins building is a peacemaker that, despite its size, presents a relatively modest facade to the open space, with some softening planting by the landscape architects Gillespies and a small-scale south-facing loggia, where you may want to sit and linger. From here you can enter the building unimpeded – public access being something that both the university and Schwarzman wanted – and pass along a broad route to its other side.

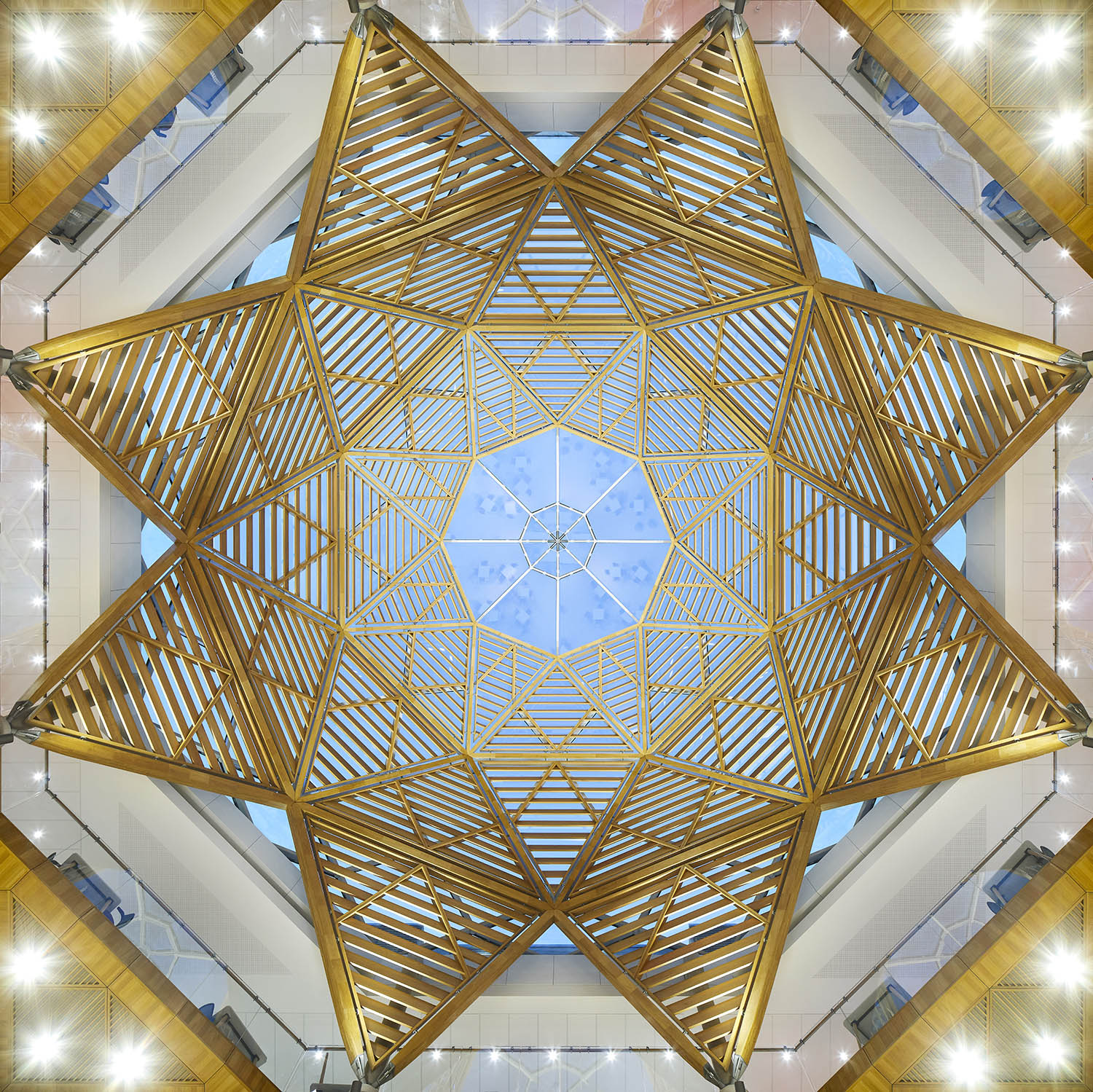

In the middle, you find its architectural tour de force: an atrium that rises to a glass dome, surrounded with galleries that give access to the faculties and libraries. This space is made of slender concrete columns and slightly arched beams, with oak balustrades in between, rising to a filigree octagonal structure overhead, whose timber slats break up the sunlight from above into patterns of brightness and shade.

‘A tour de force’: the atrium rises to a filigree octagonal glass dome surrounded by galleries

The idea is to create the opposite of the introspection and exclusion of many Oxford buildings: it is meant to be the antithesis of the inviolate squares of grass that occupy the centres of college quads. To judge by the busy but peaceful hum of large numbers of people passing through and spending time in the building, it has succeeded.

Related articles:

You can, alternatively, descend a central staircase to a re-carpeted double-height foyer from which you reach an underworld – unsuspected on the outside – of performance spaces. There is a 100-seat cinema, a 250-seat theatre, and a highly wired “black box performance lab” that, with multiple screens and speakers, can create almost any audiovisual experience you may want. There is also the 500-seat Sohmen concert hall, whose poised and largely timber interior strives with subtle curves and slight angles to create a perfect acoustic.

All is realised, as is the Hopkins way – and in collaboration with the contractors Laing O’Rourke and many specialist fabricators and consultants – with impeccable attention to such things as the precise tone and finish of the concrete and the connections between different elements.

The 500-seat Sohmen concert hall

The centre is built to Passivhaus international energy performance standards, which means high levels of efficiency, and is the largest such building so far in the UK. Despite the traditional look of its masonry, much of the centre was prefabricated in factories, which makes for faster construction and better quality, with storey-high stone walls being transported on lorries to site and craned into place.

So it’s a building that is about doing things well. You could argue that, the filigree octagon apart, some drama is lost to its oaky evenness: you could imagine another version of this project that has some fun with the contrasts and surprises of its extraordinarily rich brief. There could be more excitement, in particular, about the descent into a multivenue cultural centre underground. What it does do is to create a civilised and welcoming environment in a dignified building.

This, given that there are plenty of buildings – even well-funded ones – that do none of these things, is no small achievement.

Photographs by Hufton+Crow/David Levene

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy