Pete Townshend stares at the world in spellbinding closeup on screen. He appears hauntingly solitary and sad, although he is only 27. Something about his long face, streaming hair and suffering eyes reminds you of somebody else. He looks like Christ as the Man of Sorrows.

A track by the Who wells up in the distance. Townshend blinks, slowly, as if trying to hold on to consciousness. His gaze slides sideways as the music comes and goes, surfacing or submerged, building like thunder. At one point, a tremor runs through his whole face, lips trembling as if something is dawning. Then his head turns away into unreachable thought.

The inwardness is hypnotic, extreme. The American artist Arthur Jafa, a sound-and-vision genius, brings you so deep into Townshend’s face that it seems as if the music is being invented right here in his head. Whereupon the desperate lyrics of Behind Blue Eyes – “no one knows what it’s like to be the bad man, to be the sad man” – start to unfurl as if they were recounting Townshend’s own experience, in his past or somewhere in his future.

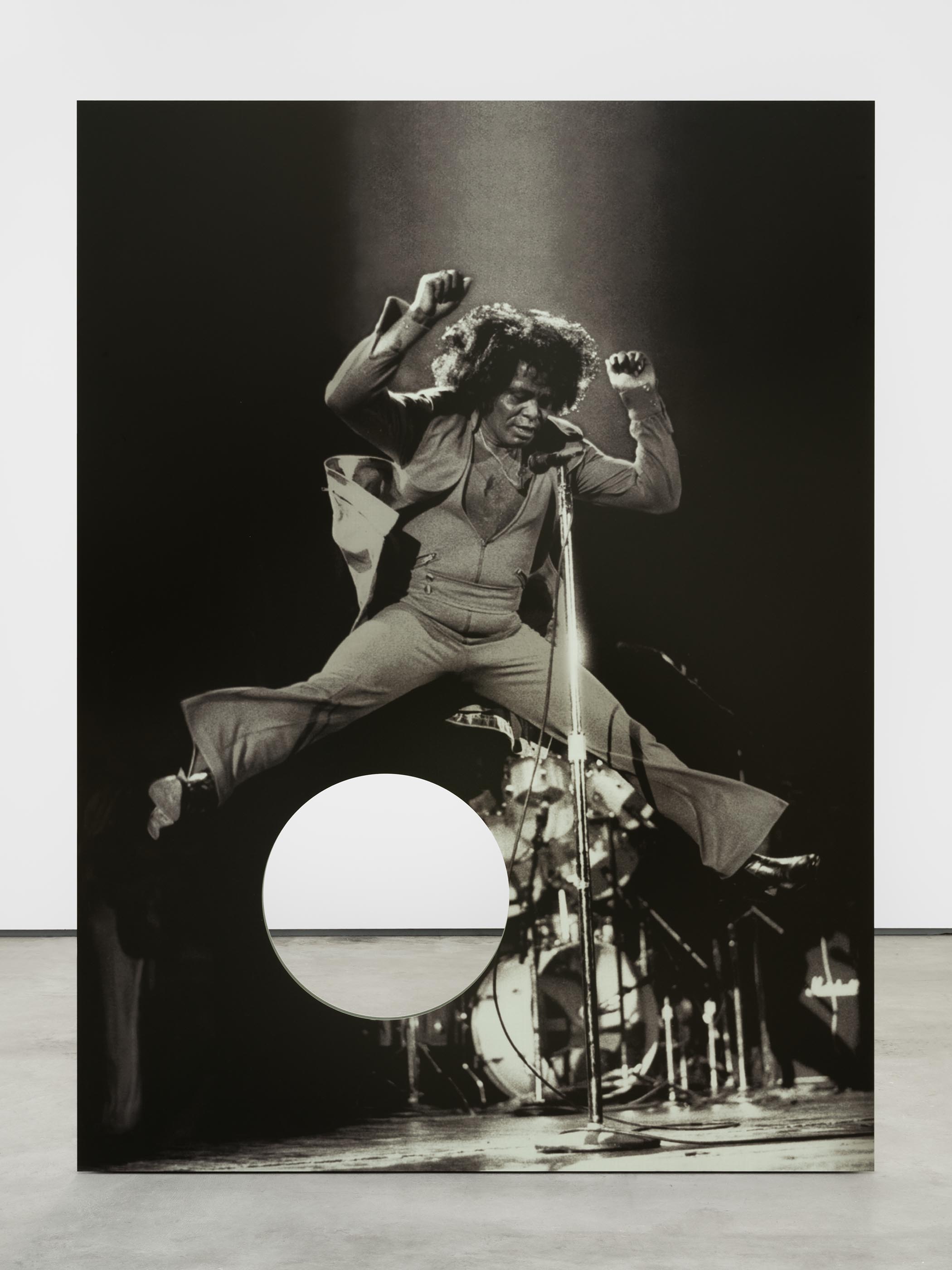

Arthur Jafa’s portrait of a spreadeagled James Brown

Jafa’s great and captivating film runs for more than 30 minutes at the Glas Negus Supreme exhibition, yet you watch incessantly to see how he cuts sound to image. Townshend himself is animated from black-and-white photographs taken just before a 1972 concert. His pupils look dilated, as if he were tripping. Time shifts back and forth. In one extraordinarily abrupt moment, the film cuts to Townshend’s trademark leap, legs scissoring as he thrashes the guitar. Volume surges into shattering colour for barely two seconds. It seems as if his dreaming head, back in the monochrome present, is about to explode.

Anyone who ever saw Jafa’s magnificent Love is the Message, The Message is Death (2016), montaging clips of black America to Kanye West’s Ultralight Beam, will know his gift for ecstatic ode. This show, a coup for Sadie Coles HQ, presents new forms of homage. A huge painting of superstar DJ Larry Levan, dead at 38, has a tiny black panther printed into its surface. Black brush strokes lead your eye into the recessive depths of a room where Kurt Cobain lies, his suicide implied only by a shadowy foot.

Wild images are screen-printed, Warhol-style, on aluminium panels: James Brown spreadeagled mid-air above a punctured void, as if spanning the globe. Iggy Pop and Patti Smith each arched in prodigious backbends. Miles Davis is there but beyond grasp, introspective yet driven in a pair of elusive prints. A counterpart to Jafa’s Townshend film is screening on the other side of the wall: back to back, and black to white, as it were. This is Jafa’s electrifying paeon to Prince.

If the Townshend portrait seems to spool through the musician’s head like a faraway concert, this film shows Prince live in Detroit in the summer of 1986. He is in the middle of performing Mutiny. Leaving the piano, which he has been playing with passionate emotion, he dances across the stage to the song’s funk-rock rhythm and what you see is almost impossible to believe.

Arms and legs making fluid triangular motions, Prince spins through space in his silk suit. His limbs appear to move, or to describe their own movements, in sequential shifts. He seems far slower than the beat, and yet somehow meets it every time. His wrists and hands, fanning upwards in a swirling climax, are so in tune with the music as to be somehow the very source of the sound. The parallel with Townshend’s expression is right there.

Prince brims and he brims, and the film takes it to the brink over and again, without ever breaking the meniscus. When you’ve watched it about a dozen times, trying to see how the performer can move his limbs in this counterintuitive way, how he hits the beat at the last millisecond, you realise Jafa’s beautiful tribute lies not just in his powers of noticing or of looping the scene, but in reorchestrating the music so that it glides onwards without any sense of repetition. The whole film lasts barely 13 minutes, but I could have watched it all day.

Cowboy, 2022, by Karimah Ashadu is a ‘gentle meditation’ on what it means to be a man

Jafa took the Golden Lion for best artist at the Venice biennale in 2019. The British-born Nigerian artist Karimah Ashadu recently won the Silver Lion for most promising newcomer. In Tendered, her pensive film studies of Nigerian men are absorbing in a quite different way.

At a slaughterhouse, where men and boys hack at cattle, her camera revolves like the beam of a lighthouse, occasionally shifting through a red filter (made from a beer keg). It is as if we are watching from inside a secret mechanism. Some of the workers seem entirely unaware of her – Ashadu has an exceptional talent for getting up close while being apparently invisible – but as their sawing, grinding, sharpening and shouting reaches a strange rhythmic score, the screen turns blood red once more.

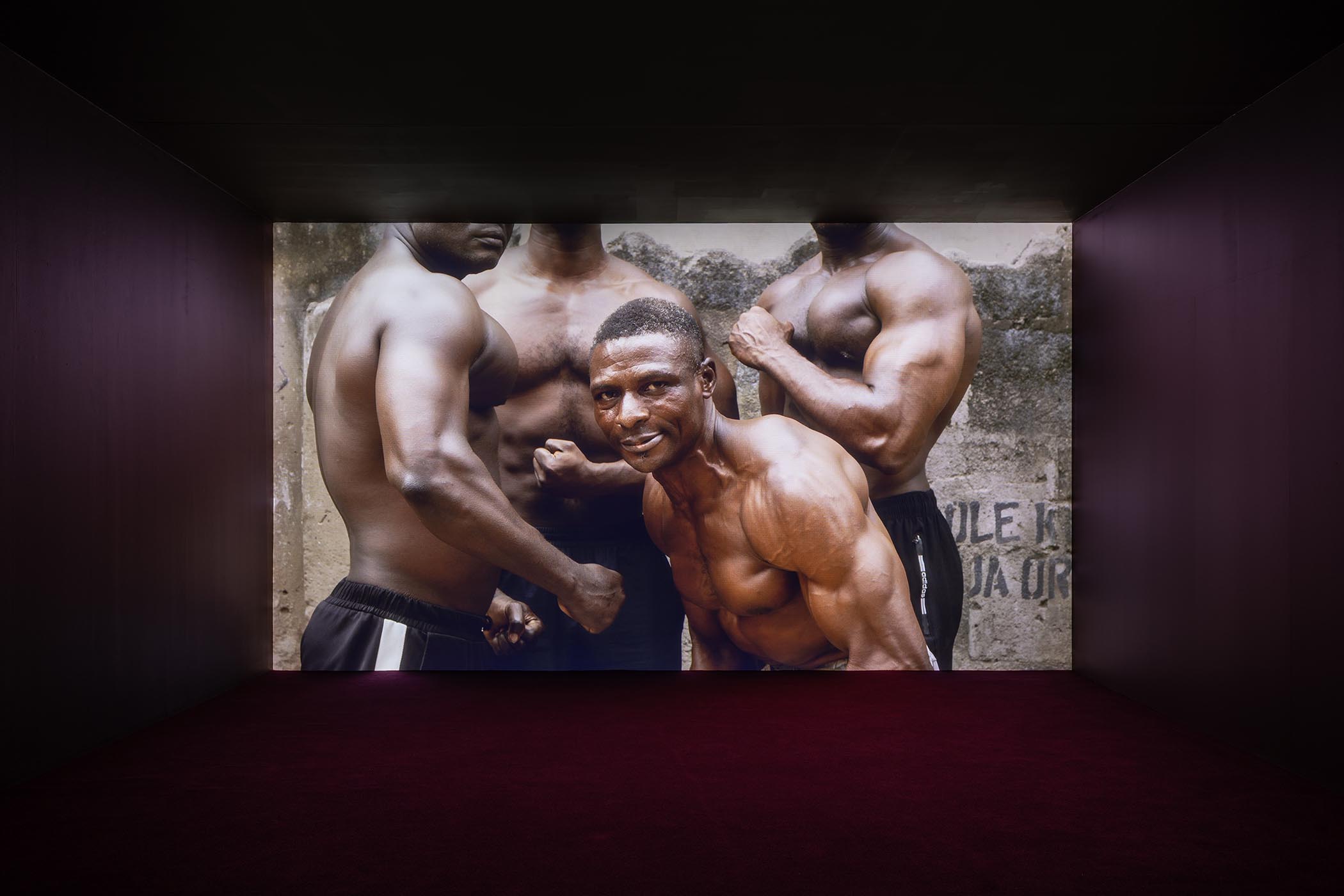

“Pain is what makes a man,” puffs one man: Ashadu’s Muscle (2025)

Bodybuilders pump iron, their muscles clenching and unclenching like mouths emitting the groans on the soundtrack. “Pain is what makes a man,” puffs one; another says this is just self-protection in Lagos. Ashadu films from above, from below, from the sweat-dripping chest to the stressed ankle. Rage echoes through the corrugated hut.

What makes a man, is it the same as what makes a Nigerian? The most exquisite film here is titled Cowboy, invoking the Wild West but set on the Lagos shore. A man and his horse are together for ever, as everywhere, as always. He speaks of this fine creature as if it were mightier by far than he. It carries them both through scrubland to the sea, where the waves rush and roar. But the horse stands firm, entirely equal to the tide. “I have learned everything from horses,” reflects the Nigerian in this gentle meditation – a timeless 21st-century portrait.

Arthur Jafa: Glas Negus Supreme is at Sadie Coles HQ, London, until 20 December. Karimah Ashadu: Tendered is at Camden Art centre, London, until 22 March 2026

Photographs courtesy of Arthur Jafa/Sadie Coles HQ/Rob Harris

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy