Seeing Each Other: Portraits of Artists

Pallant House Gallery, Chichester; until 2 November

Lucian Freud’s 1952 portrait of his fellow painter John Minton is breathtakingly acute. It shows Minton’s long face in closeup, gaunt and dejected, mouth half-open as if he might have been about to speak but has nothing to say. The skin is grey in the cold northern light, and complex reflections of both kinds, you feel, play in the huge downcast eyes. It is a tremendous painting – and it’s prophetic. Not many years later, severely depressed, Minton took his own life.

Freud was barely 30, and Minton only 34 when he commissioned this portrait. It is as if he wanted Freud to see into him, painter to painter. And it is this exceptional degree of intimacy – born out of a shared profession, as well as many different kinds of friendship – that characterises the works in this riveting show.

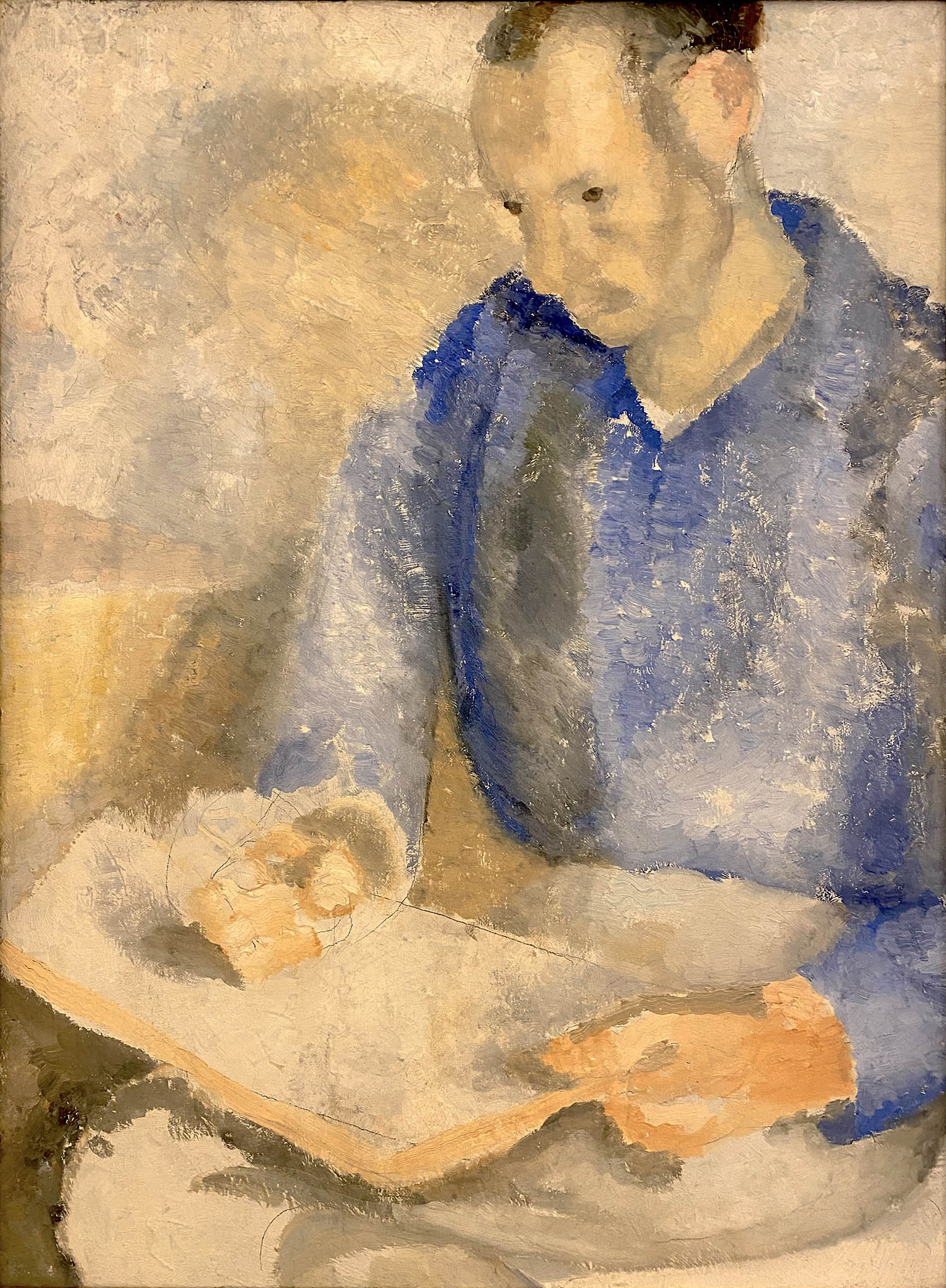

Here is Winifred Nicholson painting her husband, Ben, in 1926, his eyes fixed on something just out of the picture frame, which he is intently drawing. She knows that look of absorption from the inside, the way the eyes transmit their knowledge via the brain to the hand, obedient to every message. Winifred is doing it herself right now, as she portrays Ben: both of them oblivious to everything else, eyes sharpened by the sight of their subject.

David Bomberg paints Lilian Holt, hard at it in 1929, turning towards him from the easel at the exact moment that she is portraying him. Holt’s image of Bomberg is unforgettably vulnerable yet vital. They breathe the same air, share the same space; in fact Holt has recently divorced her husband to live with Bomberg.

Freud paints his lover Celia Paul in a striped nightshirt, the pose uncomfortably prone, sorrow one of so many nuances in her face. She returns the compliment, so to speak, 40 years later. Her Freud is also prone, but he is allowed to fall asleep. Only his head is visible in the bed, like a strange beaked bird.

Lovers fall apart; friends become rivals. William Orpen’s oil painting of his exact contemporary Augustus John, eyes narrowed, seated low in glowering darkness, is in so many ways sharper than John’s own self-portraits, subtly exposing his ego. Eric Ravilious’s startling portrait of his friend Edward Bawden at the easel is comic and yet also subversive.

Bawden is working up a somewhat rococo painting from a large sketch, his aesthetic faithfully depicted in the picture within the picture. But a cat is rudely performing its toilette on the floor behind him and a mannequin on a shelf appears to be sending up the royal bust on the mantelpiece. Rolls of drawing paper stacked against the wall resemble organ pipes, an image almost as disquieting as the guardsman’s jacket discarded on the floor. One painter’s vision is contained in that of the other.

Seeing Each Other is beautifully choreographed so that, for instance, you see Roger Fry’s (surprisingly strong) portrait of Nina Hamnett, then her portrait of Walter Sickert, then his of her, and so on, in compelling circles. Arranged chronologically, it also moves through art colleges, communities and groups, from Camden to Bloomsbury to St Ives, from the British Black Arts Movement to the YBAs, from the French House to the Colony Rooms.

Michael Andrews’s painting of the Colony Room in 1962 features the instantly recognisable shape of Francis Bacon’s head, from behind, in a teeming crowd of painter-drinkers. Freud’s amazingly suave line drawing shows him with his chest bared, trousers almost undone, posing like a Degas dancer. John Deakin shows him holding up a pair of flayed carcasses.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

John Bratby portrays his wife cornered behind a table, brutally naked. She paints him in a neat pullover and specs

John Bratby portrays his wife cornered behind a table, brutally naked. She paints him in a neat pullover and specs

The many portraits of Bacon reflect his dominance in the British art scene. Snowdon’s photographs of the young artists Bridget Riley and David Hockney, elegantly smoking in their studios, also helped to seal their image, along with a shot of Damien Hirst naked in one of his own tanks. And Johnnie Shand Kydd’s famous photographs of the YBAS drinking, dancing, snogging, laughing their heads off, depicted them as the collective embodiment of Cool Britannia.

Bridget Riley reappears as a sheaf of her own stripes in one of Lubaina Himid’s cutout figures, along with Claudette Johnson, Frida Kahlo and the late Scottish-Ghanaian artist Maud Sulter. Himid then appears in one of Sulter’s marvellous lifesize photographs. The sense of constantly evolving relationships, in relay, is evergreen through this show. The artists Chantal Joffe and Ishbel Myerscough, painting each other together over many years of friendship, have produced a startling denouement for this show, in which Myerscough depicts them both painting each others’ faces at the same time in a coruscating double portrait.

Colin Wiggins’s amazingly deft and agile etchings of some of the painters he worked with when he led the National Gallery’s Associate Artists programme show each in the act of creating his portrait. Peter Blake sits beside a half-finished canvas of the smiling Wiggins; Frank Auerbach stands beside a complex multilayered painting; Maggi Hambling is smoking and drawing on the wall. At first it seems as if Wiggins has ingeniously pastiched each artist but it turns out that he leaves a space for them to add their portrait of him. There is palpable love in these “mutual portraits”.

Levity, insight, admiration, sometimes its opposite: perhaps the most shocking portraits here depict the violent art-and-life marriage of the painters John Bratby and Jean Cooke. He portrays her with all the fierce and aggressive realism that won him critical praise as founder of the kitchen sink school. Cornered behind a table jammed with groceries, as if that were her place, she is brutally naked.

Her portrait of him, by contrast, is much more subtle. He is shown before a tidy table, in a neat pullover and specs, a placid dog at his feet. She exposes him in turn as a pillar of respectability.

This is an enthralling show, vivid with life stories as well as their expression in art. If there are rather too many photographs, it is perhaps because they are so usefully biographical. But many overlooked figures are returned to the public eye, and many artists are surprisingly connected through each other’s eyes and works. From one painting to the next, and from one relationship to another, this is a necklace of strung gems.

Images by Royal College of Art; University of Leeds Art Collection; Trustees of Winifred Nicholson; Lubaina Himid; Ishbel Myerscough, Flowers Gallery