Now 81 years old, Paz Errázuriz was working as a schoolteacher when General Pinochet orchestrated the US-backed military coup that overthrew Chile’s elected leftwing president, Salvador Allende, in 1973. Soon after, she was fired from her teaching job for belonging to a union and her house was raided by armed soldiers. In a way, she was one of the lucky ones, given that, in the dark years that followed, thousands of Chileans were imprisoned, tortured, executed or “disappeared”.

Photography became a medium for her activism when Errázuriz was 29; a semi-clandestine pursuit that, she later said, “let me participate in my own way in the resistance waged by those who remained in Chile. It was our means of showing that we were there and fighting back.”

As this intriguing retrospective makes clear, the phrase “activist photographer” only hints at the breadth and depth of her work. The exhibition’s title, Dare to Look, refers both to the often transgressive nature of her subject matter as well as the risks she took as a witness, but it is its subtitle, Hidden Realities of Chile, that perhaps best describes her mission to record that which otherwise might have gone undocumented.

Errázuriz’s democratic but often unflinching gaze places her work somewhere between portraiture and social documentary, often evoking the ways in which marginalised people find hope and strength through community and covert self-expression during times of relentless repression. Her subjects include not just the politically dispossessed, but trans communities, sex workers, itinerant performers, indigenous groups and the elderly. She describes herself as an investigator, and it is Chile – a country traumatised by terror, anxious and fearful under Pinochet’s 17-year clampdown – that emerges as the subject of her scrutiny.

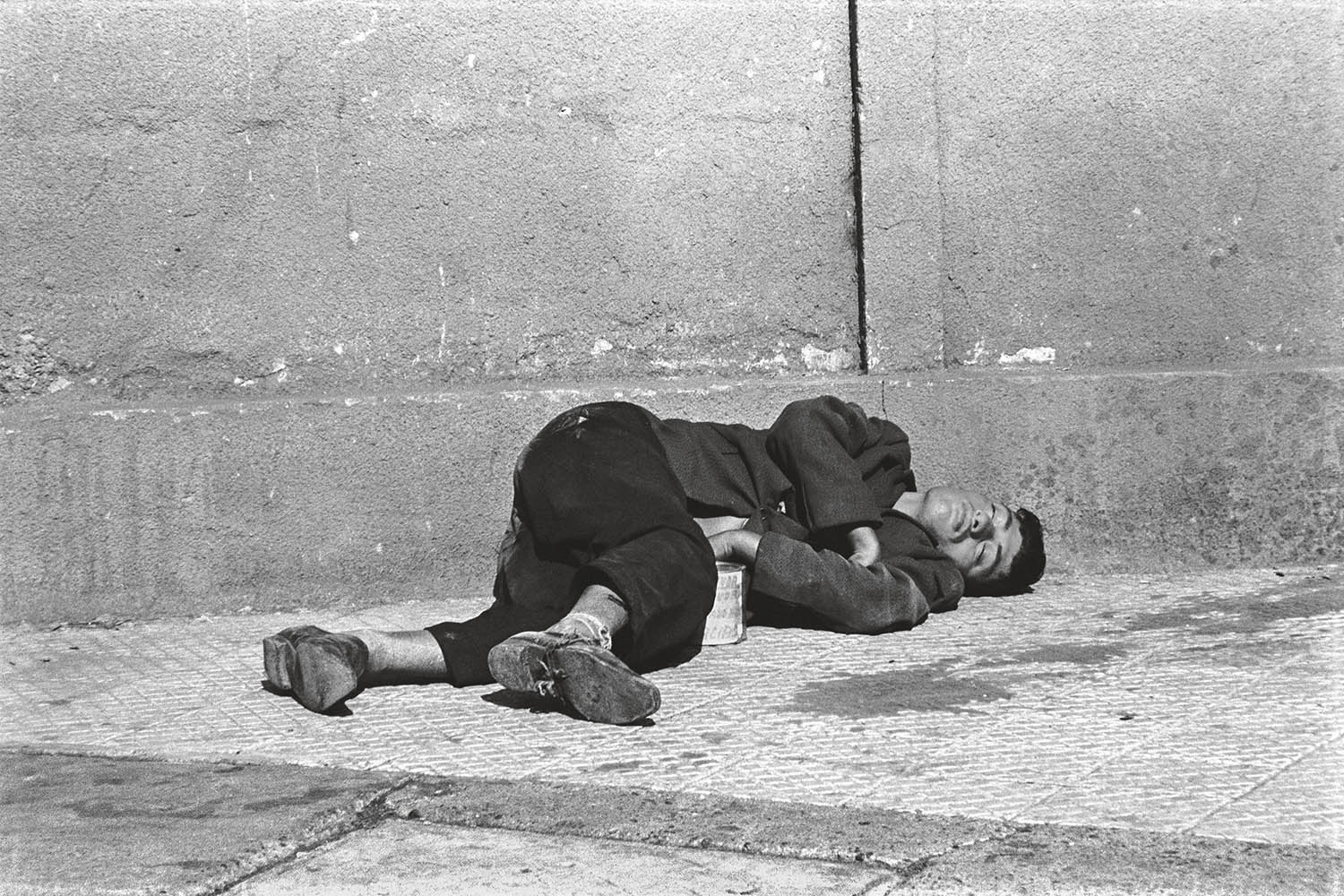

Her deceptively understated series from 1979, Los Dormidos (The Sleeping), which was made during the most despotic period of his rule, is a metaphorical portrait of her homeland at that time. It depicts people sleeping in public spaces – parks, squares, streets – as though tranquillised. An accompanying wall text elaborates on her motivation: “I sensed the silence and immense anxiety that reigned over [Santiago], but also the horror and the sorrows of the missing persons, and the violence of the dictatorship that lied and brutalised. But the street was also asleep, and didn’t rebel until the late 1980s.”

‘A haunting portrait of a kind of collective exhaustion’: Dormidos V, from the series Los dormidos (The Sleeping), 1979-1980

If Los Dormidos is a haunting portrait of a kind of collective exhaustion, her 80s series Protestas (Protest) depicts the country’s belated awakening. One grid of six monochrome pictures, all shot from elevated viewpoints, comprises images of urban insurgence that nevertheless possess a deft formal poetry. In one, a circle of people dance joyfully on a city street; in another, an armoured military vehicle directs powerful jets of water in long arcs at demonstrators huddled in a doorway. Smoke rising over the hills around Santiago is visually echoed in clouds of teargas partially obscuring a street in the Chilean capital.

Elsewhere, she captures the faces of the protagonists up close: a helmeted member of the feared fuerzas armadas (special forces), his eyes peering out from beneath a protective visor; the direct and defiant expression of a young woman holding a makeshift silhouette of one of the disappeared during a demonstration by Mujeres por la Vida (Women for Life), an organisation of which Errázuriz was an active member.

Photography, she said, was a ‘means of showing we were there and fighting back’

Photography, she said, was a ‘means of showing we were there and fighting back’

Her style shifts towards a more intimate and immersive gaze with La Manzana de Adán (Adam’s Apple), which was shot in colour and black and white between 1982 and 1987, and remains her best known series. Made in collaboration with the trans community and sex workers in Santiago and Talca, it is a masterclass in quiet observation, her subjects depicted preparing for work and relaxing in each other’s company.

Many of the portraits were made in a brothel called La Palmera, where one of her main subjects, Evelyn (also known as Eve, Leo or Leonardo) worked. Both Errázuriz and the writer Claudia Donoso lived in the brothel for a time, the latter describing the constant violence visited on the trans and queer community by the local police. In the wake of the Aids crisis, the series assumed a valedictory aspect: only one of the subjects, Coral, is still alive.

La Manzana de Adán was published in book form in 1990, nine years before homosexuality was decriminalised in Chile. At the launch in a bookshop in Santiago, it sold a single copy but it is now heralded as a landmark depiction of queer and trans communities during a dark and dangerous time.

Errázuriz is often described as a photographer of the marginalised, and, as such, her work moves sometimes uneasily between the intimate and the visceral. The contrast is starkest in the final section of this exhibition, featuring two bodies of work made in psychiatric hospitals: El infarto del alma (Heart Attack of the Soul), from 1992, and Antesala de un desnudo (Antechamber of a Nude) from 1999.

A masterclass in quiet observation’: Talca, from the series La Manzana de Adán, 1985, made in collaboration with the trans community and sex workers

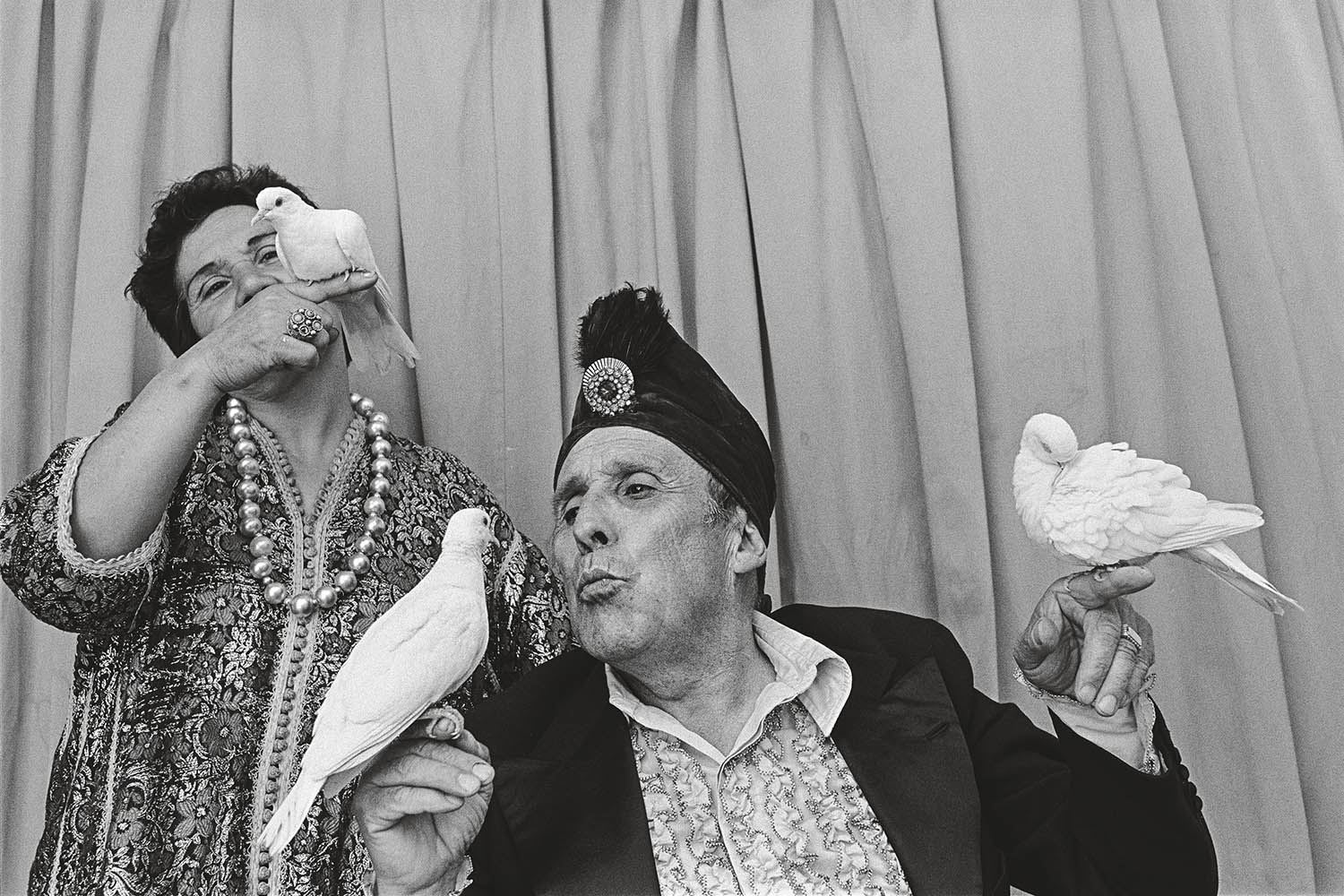

‘Itinerant performers’ are captured in El Circo (The Circus), 1988

The former is a study of deep affection, despite the dreadful conditions that patients endured in the Santiago psychiatric hospital. Couples pose for these formal portraits, which evince the emotional bonds they have formed with each other. The series is profoundly moving, a world away from other, more problematic depictions of psychological otherness by the likes of Diane Arbus or Roger Ballen.

Antesala de un desnudo, though – which features images of naked, mostly elderly, female patients in the grimy communal shower block of Philippe Pinel psychiatric hospital – is altogether more dissonant, not least because it raises thorny questions around agency and voyeurism. The critic Juan Vicente Aliaga acknowledges this photographic dilemma in the accompanying text: “What appropriate method, if any, can be used to communicate a disturbing reality? Would it be better to simply ignore it?”

Errázuriz was granted permission by the hospital authorities and, when the work was exhibited in 2004, the administration implemented improvements in patient care as a result. Nevertheless, in contrast to her other nude portraits of willing elderly subjects, these images remain troubling in their blurring of the boundary between intimacy and intrusion. “I spent a lot of time in those hospitals,” she explains, “and I was terrified by those scenes, like concentration camps. I had to photograph it.”

That compulsion to bear witness underpins this career-spanning exhibition, which is, unbelievably, Errázuriz’s first UK solo show. It is a powerful testament to her dedication, her bravery and what she calls her “anthropological approach” to depicting “the infinite possibilities that exist for survival”.

Paz Errázuriz: Dare to Look runs at the MK Gallery, Milton Keynes until 5 October

Photographs by Paz Errázuriz, from Colecciones Fundación MAPFRE

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy