A man in a desert looks into a well. What does he see – if anything – at the bottom? A key on a rope suggests the well is kept locked, but there may be nothing left to protect and this man is kneeling, as if in prayer. Moroccan artist M’hammed Kilito’s superb photograph is ominously titled Before It’s Gone.

Everyone alive has experienced thirst. To be thirsty, even for a moment, is to be connected to humanity, but how to make the condition visible? This enthralling show, Thirst: In Search of Freshwater, with its tinder-dry thatching, baked terracotta walls and parched white captions, comes at it in many different ways.

Here is the arrival of rain in a West Bank wadi, everyone plunging in for pure joy in Adam Rouhana’s lifesize photograph; and its absence in a stark Raqs Media Collective installation that recreates an ancient Indian stepwell beneath pitiless dry skies on a never-ending video loop. Here is a stunning Iranian ewer incorporating an ingenious inner tank for ice, providing cold drinks in an 18th-century desert. And an eerie photograph of the spot where the notorious pump on Broadwick Street poisoned Soho with cholera in 1854: water you could not drink.

Water is life. Confirmation of this is everywhere here, from a lead pipe to a dead camel, its hump drained

Water is life. Confirmation of this is everywhere here, from a lead pipe to a dead camel, its hump drained

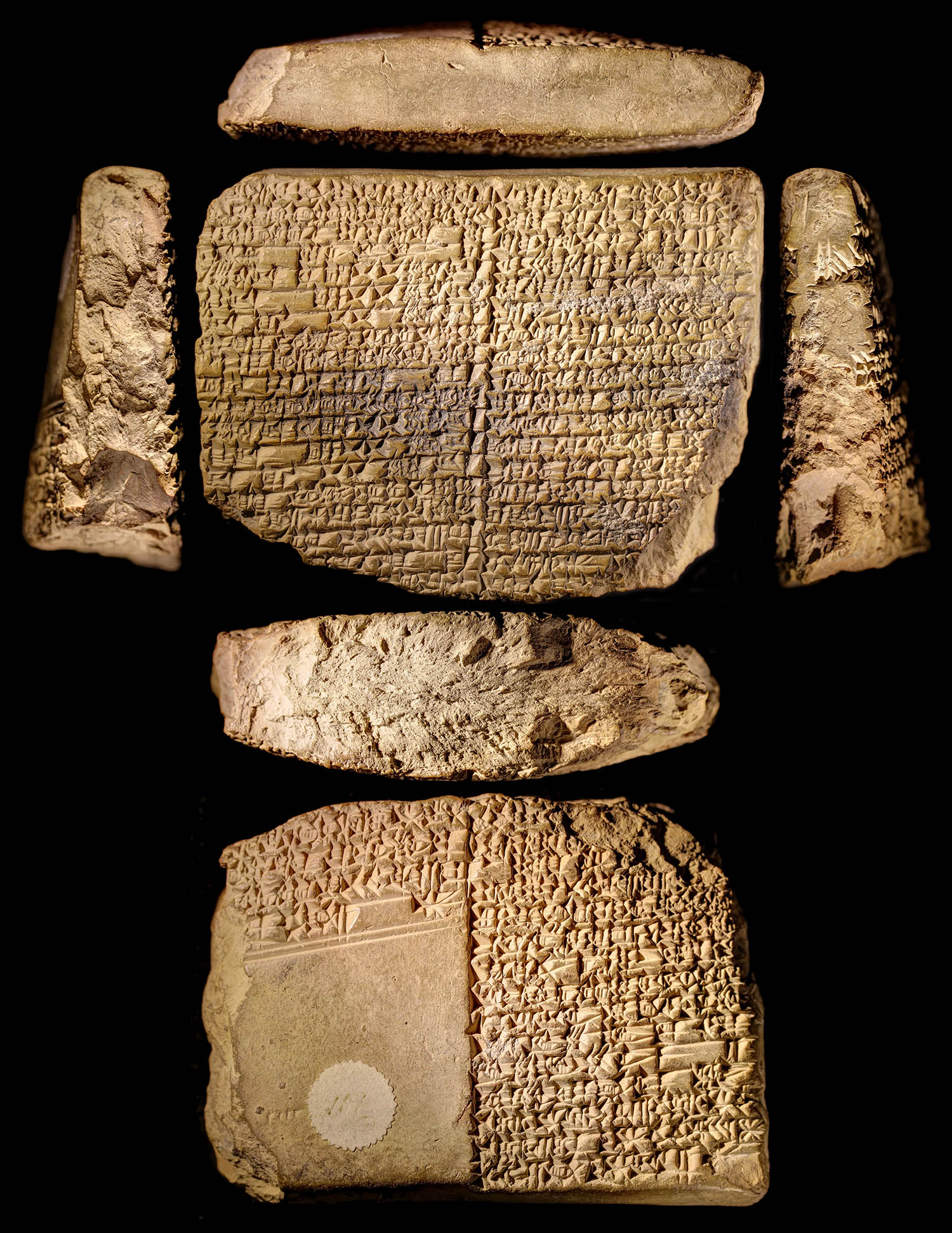

The show opens with a staggering sight: a third-century clay tablet not much bigger than your palm, so densely carved with cuneiform script it’s like microscopic embroidery. What it tells is the Epic of Gilgamesh, composed about 2100BC, in which King Aga threatens to cut off King Gilgamesh’s water supply from the Euphrates if he does not hand over his subjects to dig wells for Aga’s kingdom.

This is the earliest account of a war over water. Later, the poem relates the story of a universal deluge sent by the gods to destroy humanity; for the deluge, read Noah’s flood.

About 40% of our planet is arid. To be thirsty is to understand the condition of Earth. Europe had its worst drought in half a millennium in 2022 and still we have to learn from other civilisations. One section of this show is devoted to the qanat, an underground water transport network originating in Iran about 3,000 years ago. It conducts water from mountain foothills across immense deserts, relying solely on gravity. An exquisite Persian miniature shows gardens flourishing in parched earth, irrigated entirely by diversions of the qanat.

‘A staggering sight’: the third-century Gilgamesh and Aga tablet

Where does water come from? Partly, it arrives as the gentle rain from heaven. A graphic section runs all the way from the unexpected downpours that fell upon Sinai during Covid, restoring dead trees to life, to George du Maurier’s mordant 1869 cartoon of a depressed Englishman going to the country to be healed, only to find himself surrounded by heavy black rods.

But almost two-thirds of the planet’s freshwater is frozen up in glaciers. Thirst does not always go with heat. A booth at the centre of the show presents Susan Schuppli’s Ice Records, in which the artist’s recordings of glaciers melting from Canada to Scandinavia and the Himalayas can be heard alongside her words and images. Bubbles trapped in ice for thousands of years – records, you might say, of the atmosphere at that time – are gradually released with the melting of the glaciers, causing a captivating variety of melodic drops and crackling pops. Alas, if we can hear them at all, it is because these “ice records” are disappearing.

Water is life. Robert Macfarlane, in the marvellous catalogue – which also features writings by Elif Shafak, Rebecca Solnit and Ocean Vuong, among many others – proposes that the term “Anthropocene” is scarcely sufficient to describe our epoch (or any other). “Hydrocene” is his word. Confirmation is everywhere in this exhibition, from the lead pipe that carried water round the house of Empress Messalina 2,000 years ago to the poor camel, dead in the Sahara for lack of water today, its hump entirely drained, no longer the ship of the desert.

Animals thirst; rivers thirst. Morocco, in drought since 2018, has empty gullies everywhere. Beirut River – justly given its own section – is constantly abused, forced through concrete basins, choked with sewage, dying for a drink of fresh water. Indeed, anyone expecting the human thirst of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner, marooned on his ship with nothing but undrinkable seas all around him, will find that this show is more about the planet’s supplies of water: their terrible lack or their ruinous abundance in the form of floods.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The most brilliant work here, in terms of visual power, is by the South African artist Gideon Mendel. Nothing could more perfectly describe the aftermath of flooding than his five-screen installation Deluge.

People canoe, paddle and row down the streets of their towns, now transformed into rivers, all over the world. The movement of pole and oar ripples from one screen into the next, connecting human experience everywhere. Now the water rises and they canoe through their own tower blocks. Now it rises again, up to their very shoulders.

Swimming against the current, crops ruined, the only sound the sinister lapping of the flood itself, survivors hold carrier bags – and bottled drinks – aloft. For flood can be as fatal as drought. Water, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink.

Thirst: In Search of Freshwater is showing at the Wellcome Collection, London NW1, until 1 February 2026

Photographs provided by M’hammed Kilito and the John Rylands Institute and Library