In the summer of 2000, Julian Hoffman and his wife, Julia, read a book review in an RSPB magazine and it changed their lives. The book was Prespa, by the Greek biologist Giorgos Catsadorakis, a paean to a remote lake in the high borderlands of northern Greece, where pelicans and bee-eaters soar and wolves come down to drink at dusk. They ordered the book, read it aloud, drank wine, and by the end of the evening had decided to go there. Not for a visit, but for good. They packed up their London lives and set out for a part of the world they’d never seen.

That moment – improvised, improbable, sublime – sits at the heart of Lifelines. In some ways, this is a fairly traditional memoir, à la A Year in Provence, but it’s a lifetime, and there are bears. What elevates it, though, is the beauty of Hoffman’s prose. He is a first-rate writer, deftly navigating the difficult line between lyricism and schmaltz. Just as important is the book’s structure of connectedness, present in both its theme and its method: the sense that everything is related, and that this relatedness hums not only at the surface but in the deeper strata of the text.

Hoffman has always been a writer not just of ecosystems but of thresholds. His previous book, Irreplaceable, explored the disappearance of places and species; beneath that, it was about loss in a broader, more human register, an elegy for all that slips away, unnoticed, until too late. Lifelines extends and deepens that theme. Written in part during the pandemic, it opens with wrens – notoriously solitary birds – clustering together in an abandoned swallows’ nest outside the Hoffmans’ front door, seeking warmth in shared refuge. “Reimagining shelter,” he writes, “is key to forging a common path into the future.” The wrens are not metaphor. They are kin.

Hoffman is a first-rate writer, deftly navigating the line between lyricism and schmaltz

Hoffman is a first-rate writer, deftly navigating the line between lyricism and schmaltz

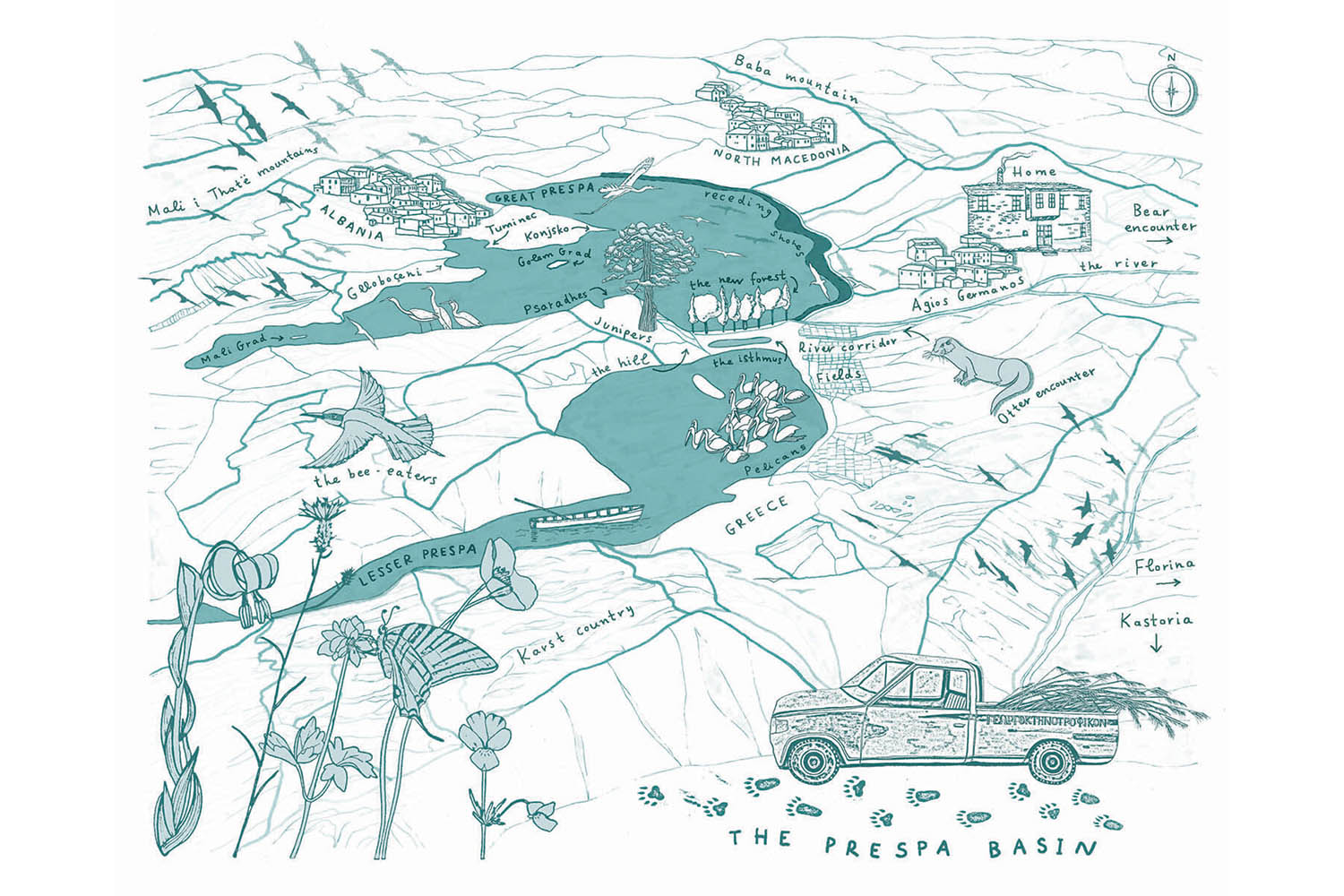

Prespa, the ancient lake system where the Hoffmans made their home, is a crucible of entanglement. Three countries meet there – Greece, North Macedonia and Albania – bringing with them multiple languages, alphabets, and centuries of war, migration and uneasy peace. The lake is ringed by mountains, dotted with ruined hermitages, and scorched in summer by fires that turn the skies grey with ash. Swallows arrive from Africa and nest under the eaves of the post office. Otters breed in the shallows. Bears break open ant nests for eggs. In a world of fences and surveillance, Prespa remains defiantly porous. Its borders exist on maps but not in water.

Hoffman does not trumpet these facts. He unfolds them – gently, patiently – through prose of remarkable clarity and grace. Consider his observation of pelicans over the lake: “the wondrous doubling of forms when skimming so low over the lake that you could barely slide a knife between the bird and its reflection”. Or his quiet fury at the decline of the regent honeyeater, an Australian bird now so rare that its young can no longer learn their own song, mimicking instead the calls of other species. This loss of voice is called the Allee effect, he writes, and it “can mean the collapse of culture as well as number”. In such lines, ornithology becomes moral philosophy.

Yet Lifelines is not simply a book about grief. It is, more essentially, a book about shelter and about being sheltered. Again and again, Hoffman returns to acts of welcome: the local man, Vasilis, who meets them on arrival and helps them find a house; the cuttings of lilac and evening primrose planted by Vasilis’s mother in their garden; the friends, and strangers, who come together to save their house when the chimney catches fire. These are not minor anecdotes. They are lifelines; gestures that bind strangers into a shared story, that make home not a possession but an act of reciprocity.

That, ultimately, is the great power of Lifelines. At a time when nature writing so often descends into therapeutic solipsism – a recovery narrative, a mindful walk, a deer glimpsed in a moment of middle-class despair – Hoffman offers something altogether more radical: an ethic. What we need, he suggests, is not catharsis but commitment. Not only to observe, but to serve. And above all, to leap: into risk, into uncertainty, into community.

That message is the book’s crescendo. Lifelines is not just beautiful, it is quite literally encouraging. It will make you brave. To those waiting for the right moment, the safe path, the clearly marked route, Hoffman offers a challenge: throw yourself towards the dangerous edge of things. You may land in ash. But you may also wake at dawn beside your own Julia, watching pelicans glide over your own Prespa.

Lifelines: Searching for Home in the Mountains of Greece by Julian Hoffman is published by Elliott & Thompson (£18.99). Order Lifelines at observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

Illustration from Lifelines by Matina Galati

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy