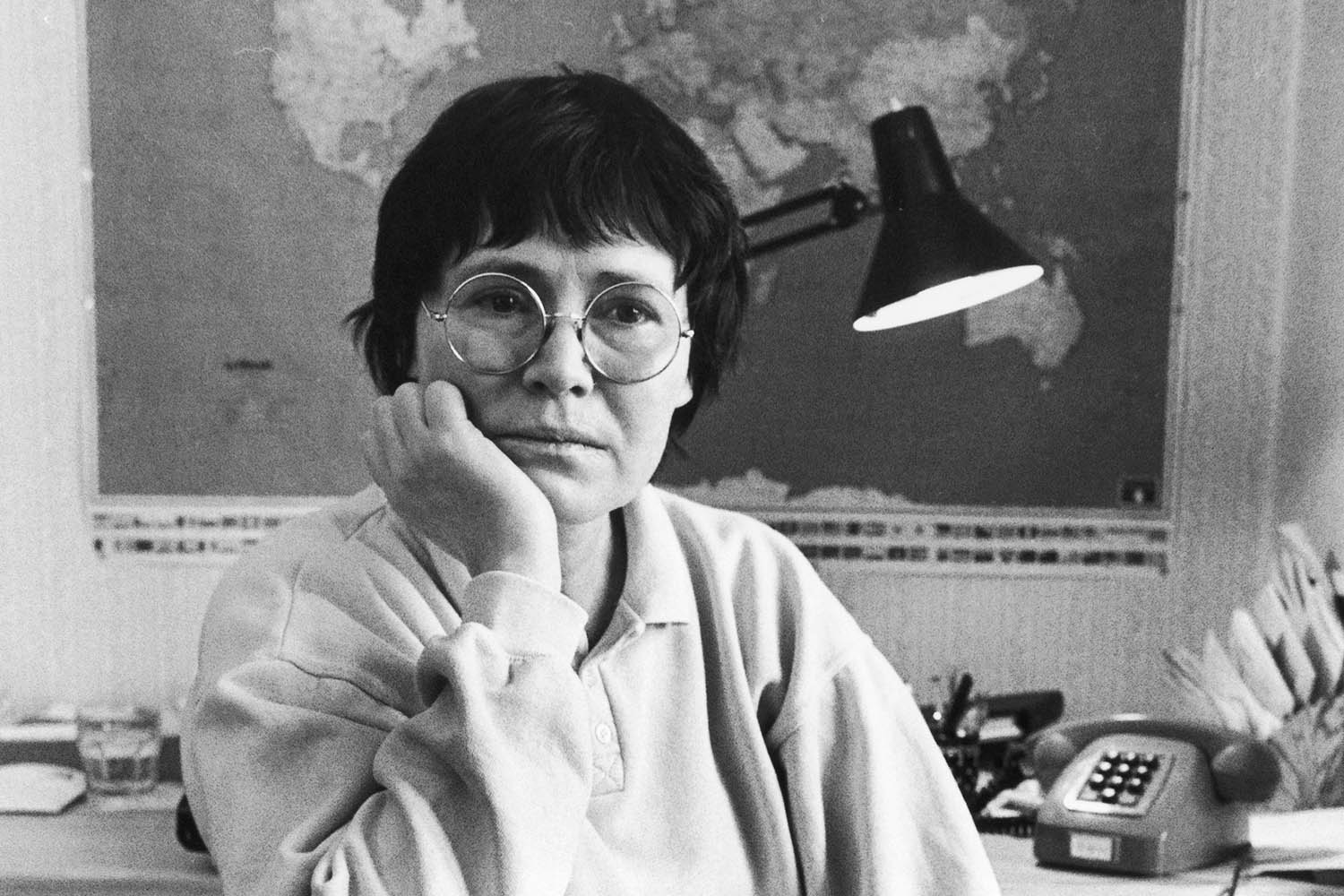

In her slender, eviscerating memoir, The Illiterate, Ágota Kristóf (1935-2011) charted her escape from Hungary following the Soviet Union’s savage put-down of the 1956 uprising, and her life as a refugee. Although her arrival in Switzerland – with her husband and baby daughter – ensured her physical safety, it meant she had lost her homeland, her history, her mother tongue and, from the moment she stepped across the border, seemingly all possibility of becoming a published author. Instead, for the next five years, she laboured mutely in a factory, slowly and painstakingly acquiring enough French for the writer within to establish herself.

The internal mechanics of the exophonic writer – one who writes in a language other than their own – have long exerted a pull over the literary imagination. By the early 20th century, the native Polish speaker Joseph Conrad had decisively swept away all notions of its impossibility in English. Vladimir Nabokov, who wrote in English from the 1940s after fleeing Russia, later covered the process with an internationalist glamour, and Samuel Beckett’s conscious decision to eschew Hiberno-English for French – out of “a need to be ill-equipped” – validated its importance to mid-century modernism. Despite this, and the generations of exophonic writers before and since – from Sholem Aleichem to Anaïs Nin, Chinua Achebe to Jhumpa Lahiri – the inevitable question lingers over whether or not something of the soul is lost in the gap between intrinsic and extrinsic language.

Choice is a vital factor and it’s clear that, although the acquisition of a second language released Kristóf from silence, she felt she was only placed into a looser muzzle and the prose that resulted was in some way injured. She would eventually hew the acclaimed Notebook trilogy from her never-fluent and self-declared “enemy language”, French, but the wound created by the loss of her linguistic homeland never healed and the experience of exile, both internal and external, was something from which she could never free herself.

It is everywhere in evidence in I Don’t Care, a newly released collection of her short stories translated by Chris Andrews, who demonstrates a fine ear for preserving the different registers of mourning produced by Kristóf’s cast of wandering characters as they are thwarted by their inability to either fully escape the past, or step back into the rivers of homeland twice. While frustration and apathy are rife throughout, Kristóf never shies from the deeper darknesses of human nature – the gross amorality of The Notebook’s twin boy protagonists, clawing survival from the bodies of everyone around them during an unnamed European war, is the template from which she does not deviate here. Such brutality is often presented to readers in an unforgiving manner: if she does not pity her own characters, why should she take pity on us? However, as with that other famous escapee into French from behind the iron curtain, Milan Kundera, Kristóf’s characters’ defeats and confusions are rarely rendered through pathos alone but served up with a richly entertaining disdain for sentimentality.

In The Writer, Kristóf takes on the pomposity of those who, having never had to struggle to create a means of expression for themselves – and from that fortunate position still have not managed to write a line – remain, nevertheless, convinced of their dormant literary genius. “I sense, I feel that I am a great writer, but no subject seems good enough, big enough, interesting enough for my talent.” As personally infuriating as such complacency must have seemed to her, Kristóf allows the distinctly Joycean “Solitude, silence and the void – that horrible trio” to press down upon the would-be writer until the pressure causes the roof to blow off, connecting them up directly with infinity and opening their mind to all the possibilities of literature. It’s transformative and leaves the budding genius with, if not yet a worthy subject, at least a voice. But, with typical detachment, Kristóf then abandons them to the nightmare from which no good writer can awake: the infernal and inexorable transmission from within that is the voice of doubt.

By contrast – though sharing a few bones with Kundera’s The Unbearable Lightness of Being – The House is about the weight of exile and how even the act of returning is unable to lift it. When a small boy moves house, not due to any political upheaval, simply because his parents want a prettier, bigger one, he is cleaved in two and set on a lifelong course of yearning for his lost first home. Initially, he makes regular return visits to it. But, on finding another person living there, he feels shattered by the house’s betrayal, so crosses the sea to get away. Now an adult living in the city, he boasts to his old home about how far he has travelled – only to then commission an architect to faithfully recreate the house, paying special attention to the beloved veranda. His longing, however, cannot be fooled, and the reproduction fails to replicate the feel of the original. Eventually, now an old man, he returns to the house to find a young boy playing on the veranda. He approaches and asks why the boy is looking at the moon. When the child responds that he is not looking at the moon but at the future, the old man confesses this is where he himself is from and that all it consists of are “dead, muddy fields”. Suddenly recognising his future self, the child starts to cry and, as comfort, the old man suggests perhaps the future is only dead, muddy fields because he left the house in the first place. Reassured, the child declares he will never leave, and the old man sits on his veranda smiling, dying, and looking at the sky.

Frustration and apathy are rife throughout, but Kristóf never shies from the deeper darknesses of human nature

Frustration and apathy are rife throughout, but Kristóf never shies from the deeper darknesses of human nature

Similarly, in The Streets, a character spends his childhood walking the streets of his home town, only leaving in order to pursue his music studies. His great love for where he comes from works its way into his performance, and he is ridiculed by the other students for his sentimentality. Despite his talent, he gives up a promising career to return to his first love – his home – to become a music teacher. Such is the price exacted by love and home that, even after his death, his ghost is “obliged to return year after year – for eternity – and haunt the streets he feared he had not loved enough”. The city has a natural indifference to this love: when the ghost worries he may become a frightening presence on his beloved streets, the narrator points out that, for the children of the city, “it made no difference at all whether he was alive or dead”.

The collection is studded with similarly delightful, and hurtful, gems. The subjects that pass under Kristóf’s sharp eye, and sharper scalpel, range from female domestic servitude imposed by a self-congratulatory male feminist-type in The Invitation, to the impossibility of overcoming the failure of one’s innate nature in Wrong Numbers. There is also exile from reality – as well as homeland – in A Northbound Train, and the unwinnable war against the life-altering disinterest of progress in The Countryside, as a man who moves there for a cleaner, healthier life winds up with a motorway and incinerator being built on his doorstep while, back in the city, a low traffic neighbourhood is established. But binding them all together is the belief – according to the murderous narrator of The Big Wheel – that “the only thing that can scare you and hurt you is life, and you know life already”.

I Don’t Care by Ágota Kristóf and translated by Chris Andrews is published by Penguin Classics (£10.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £9.89. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photography by Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images