By the time I came to Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking, I was both desperate to quit vaping and convinced I never would. I had picked up the habit two years earlier, despite never having smoked. As a health-conscious millennial, I would have sooner bought a gun than a pack of cigarettes – but sampling my gen Z friends’ pastel cubes and sleek pens seemed more like staying culturally current than flirting with addiction.

By late 2023, I was buying my own disposables and vaping at home throughout the day. It seemed the perfect little treat: a zero-calorie sweet hit, the same price as a takeaway coffee but longer-lasting. I knew vaping probably wasn’t harmless, but in the absence of conclusive evidence, there was a childish glee to acting so out of character, doing something “bad”.

With time, however, the illicit pleasure waned. I didn’t like feeling distracted while out with friends and panicky when my vape wasn’t within reach. The contradiction between my gym-going and chain-vaping seemed less whimsical and more plainly idiotic. The cost, too, stood out as obscene in my otherwise careful budgeting. I quit multiple times, for up to a month, but always caved after a few drinks, a stressful day, or because of the false belief I could have “just one”.

By last October, I was lying to my friends about still vaping, convinced I’d be an addict for ever. Then a taxi driver told me about Allen Carr. I’d commented on the beautiful morning, a reprieve from the recent “horrible” weather.

“It’s been raining,” he corrected me, firmly. “If you change your thoughts, you can change your experience.” He’d learned that from Carr’s book, he said. It revealed to him that he didn’t actually want or need a cigarette – he’d merely been buying into an illusion. After that, his desire fell away. Would it work for vaping, I wondered, gripping the Lost Mary in my pocket. “I don’t see why not,” he said, adding gnomically as I got out of the cab: “You can always do whatever you want.”

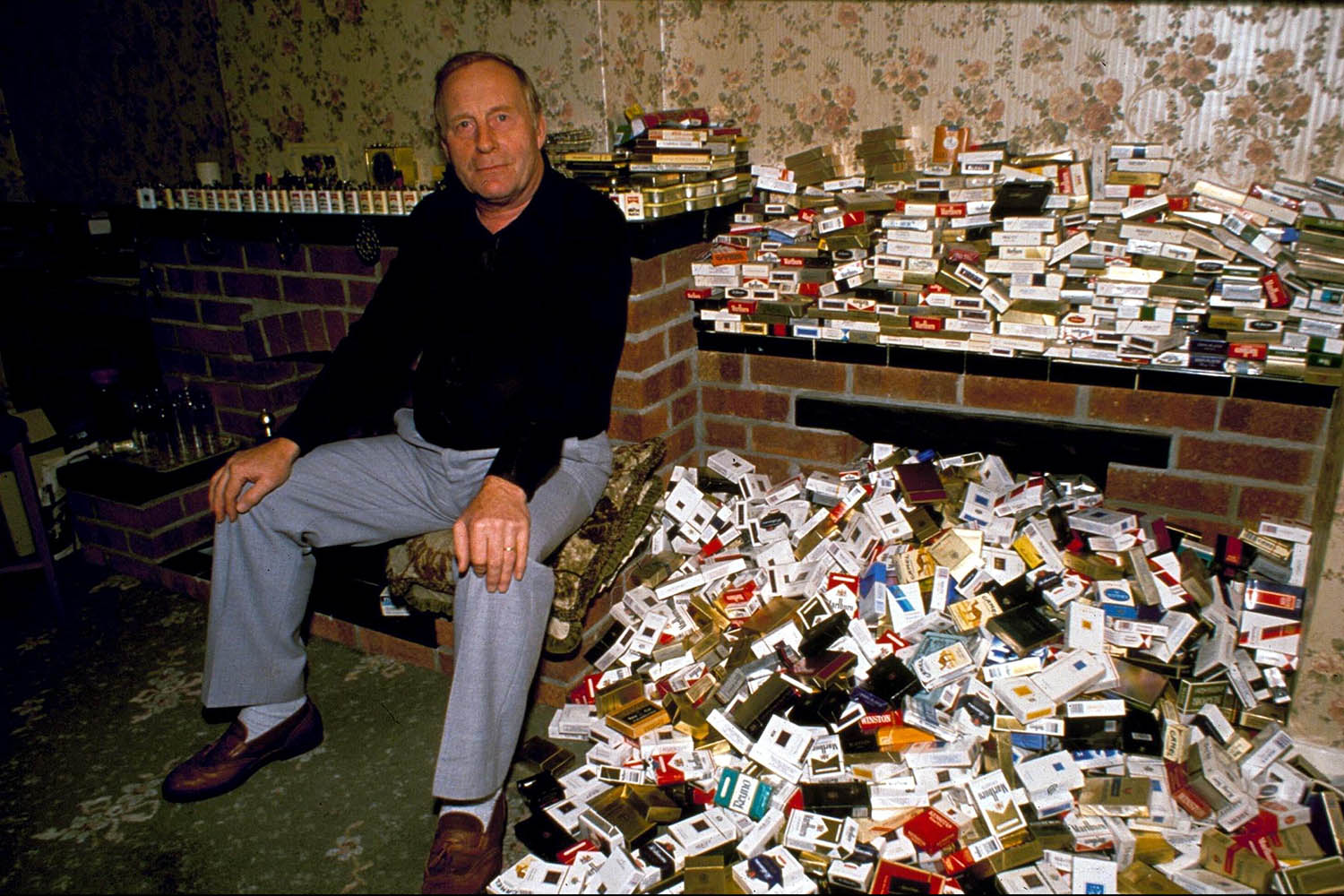

I borrowed the book from the library, vaping as I read, as instructed. Carr, a former accountant from south-west London, wrote it in the early 1980s, having unexpectedly cured himself of his own 33-year, 100-a-day smoking habit, then repeated his success with private clients. The global Allen Carr’s Easyway phenomenon followed, encompassing clinics, group seminars and dozens more books as he applied his method to virtually every vice and addiction.

Though the live seminars are the company’s gold-standard offering, the Easy Way to Stop Smoking book has sold more than 15m copies, and amassed a 4.27 star ranking on the Goodreads website. (By comparison, Anna Karenina has 4.10.)

It’s not for the fine prose. At first, I found the book dated and grating in its 80s bravado. Carr wasn’t interested in science, but he loved caps-lock exaltations, exclamation points and visual metaphors.

Related articles:

Nicotine was a “little monster” inside me, I learned, that demanded feeding. Smoking was like wearing tight shoes all day, just for the relief of taking them off. Or applying expensive ointment to a cold sore, even after learning the ointment was making it worse.

I read in bed, rolling my eyes. But after a few nights, I noticed I wasn’t pouncing on my vape upon waking. On night four, I finished the book – and, I felt, my last-ever Lost Mary. Quitting this time felt different – more settled, like the subject was no longer up for debate. In town later that day, passing the many vape shops, the sight of the boxes made me feel queasy. I even dreamed about buying a vape – and throwing it away, unopened. I woke up feeling giddy, free and a little perturbed.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

A week before, quitting vaping had seemed like an impossible task, my essential failing, my fate; reading a short, simple book had made it more or less effortless. It made me question my assumptions of what was possible with the written word.

My younger sister and a friend then listened to Carr’s audiobook. Four months later, we’re all still vape-free. What was this seemingly magic “method”? Who was this former accountant? And were there other seemingly insurmountable blocks in my life I could be tackling the Easyway?

Carr stumbled upon his method in 1983, after many anguished attempts to quit the “hard way”. An appointment with a hypnotherapist failed to cure him of his desire to smoke, but usefully framed it as “just a nicotine addiction”. When Carr’s son John gave him a medical textbook that explained withdrawal created an “empty, insecure feeling”, the idea clicked.

Carr likened his method to a “magic eye” image, snapping into focus to reveal “the situation of the smoker as it really is… We had all been victims of an ingenious confidence trick, perpetrated on a gigantic scale.”

Carr considered himself instantly cured. His wife, Joyce, now 96 and a never-smoker, was sceptical. “He’d tried so many times,” she tells me by phone from Spain’s Costa del Sol, her longtime home.

After five months smoke-free, Carr started giving private sessions from their home in Raynes Park, south-west London, advertising in the local newspaper. Joyce had misgivings about his money-back guarantee, but Carr told her that smokers would be so grateful to be cured, they would pay more than the £30 they were asked. “And he was quite right,” she says. Joyce recalls late-night calls from across Britain, and clients arriving from Italy, the US and South Africa. “It really did take over our lives.”

Carr self-published his book in 1983, to reach more smokers than he could treat in person; Joyce’s daughter Madeleine typed up his handwritten draft. At the back was a page reading: “Yippee! I’m a non-smoker!” Readers were invited to tear it out and post it to Carr. “We got loads of those back – thousands,” remembers Madeleine, now 73 and an Easyway company director. “We thought: ‘There must be something in this.’”

Penguin published Carr’s book in 1985, after broadcaster Derek Jameson claimed it “forced” him to quit smoking on BBC Radio 2. More celebrity endorsements followed, including from Richard Branson, Ruby Wax, Anthony Hopkins, Anjelica Huston, Ellen DeGeneres, Nikki Glaser and Victoria Coren Mitchell.

In January, Mel Gibson credited Carr’s “silly” book with ending his 45-year smoking habit on Joe Rogan’s podcast: “It worked like crazy.” Online, many people liken it to magic, or a miracle; rationalists say hypnosis. In fact, it’s more like cognitive behavioural therapy (the Easyway company prefers “cognitive restructuring”).

Carr died in November 2006 of lung cancer, aged 72. His widow links it to years of leading sessions in smoke-filled rooms. Spreading the method “became kind of a religion for Allen”, says Joyce; he told her it “was going to cure the world”. Even now, she says, “knowing Allen as I know him… he would have felt that it could get even bigger”.

Despite presences in more than 45 countries, Easyway still has its headquarters in Raynes Park, just a mile from the Carrs’ former home. The three-storey building is an active clinic, holding group seminars, and is a shrine to Carr’s vision. His framed portrait hangs by the front desk, across from a stand of books bearing his name (most published posthumously), promising freedom from not just nicotine but alcohol, sugar, cannabis, cocaine, insomnia, gambling and even debt.

The latest title is The Easy Way to Enjoy Exercise, co-written by Robin Hayley, Carr’s friend and former protege, now the company’s global chair. Hayley pursued Carr for a job after successfully quitting smoking at one of his seminars in 1989. “I just left that room and I had no desire to smoke – it was extraordinary,” says Hayley, still boyishly awed. “I did think: ‘Is this guy some sort of magician?’”

After impressing Carr with his persistence, Hayley was brought on to help open Easyway’s second clinic, in Birmingham, and trained to lead seminars. Even today, all Easyway therapists are required to have successfully quit using the method themselves.

“I thought: ‘Everybody needs to know about this,’” says Emma, who leads the stop smoking seminar I sit in on Zoom. She kicked not only nicotine but also alcohol and sugar using Carr’s method. “It’s lovely to be able to share it.”

Hayley was motivated to join Easyway by the commercial potential as much as by spreading the word. Having kicked an addiction to heroin (not by using the Easyway method), he was influential in convincing Carr that the method could be more widely applied. The key – he says, warming to his theme – is to remove the conflict of will, and with it the need for willpower. By stripping away the social conditioning, “you realise that the drug, whatever it is, does absolutely nothing for you… so when you quit, you don’t feel deprived”. For example, Hayley’s new book counters the “brainwashing” that exercise is necessarily challenging, unpleasant, a punishment or a chore: “In reality, it’s great fun.”

Since the first spin-off title in 1997, The Easyweigh to Lose Weight, Easyway’s bibliography has grown to resemble a laundry list of modern ills: vaping, social media and tech addiction, emotional eating, emotional drinking, “good” and “bad” sugars – even fear of flying.The next book in the pipeline, due later this year, addresses anxiety, while a new gambling title is planned for 2027 to reflect modern temptations and formats. Future topics being considered (but not confirmed) target ultra-processed foods and porn.

“We try to look at where we think the biggest need is,” says Paul Baker, Easyway’s global chief executive designate. The company often receives suggestions, or requests: “A lot of people are writing in about sex addiction – male and female.” But, Baker explains, the company has to balance the need to stay current with fidelity to Carr’s original method, which emphasises quitting nicotine cold turkey. Subsequent titles tackling different addictions “obviously do have safeguards around that” to reflect the risks – such as with alcohol – of stopping abruptly. But some substances, including opioids, have been deemed too difficult to take on. “There are some you do need to taper off… It’s changing the method, and we don’t want people to get confused.”

I just left that room and I had no desire to smoke – it was extraordinary

I just left that room and I had no desire to smoke – it was extraordinary

Hayley is less circumspect. Now more than ever, he says, he believes that Carr’s method can be applied “to any problem which is essentially psychological” – with one exception. “It’s a highly rational method… so I don’t think we’ll manage to apply it to insanity.”

Mental health is not an issue for me – but procrastination is. So is stopping eating after just one or two biscuits. After my effortless success with The Easy Way to Stop Smoking, I wanted to believe that all my problems could be similarly dissolved. But I’m sceptical that Carr’s method for nicotine can be applied so broadly – at least, not with the same results. You can’t easily isolate and banish food or tech from your life the way you can nicotine, marijuana or alcohol. And though relying on willpower alone is unsustainable and generally counterproductive for weight loss, demonising food groups isn’t helpful either.

Easyway claims its success rates are uniformly high, but only the stop-smoking seminar has received much scientific scrutiny. The most robust research has in fact been funded by the company – but conducted independently – with the goal of cementing its credibility.

In 2020, a randomised controlled trial carried out by researchers at London South Bank University concluded that the Easyway seminar was just as effective as the gold-standard stop smoking service offered by the NHS, which combines behavioural and pharmacological support such as nicotine patches and gum.

In 2022, the Easyway seminar was recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) for use on the NHS as a cost-effective, drug-free option for smokers wanting to quit. English councils may now elect to offer residents funded spots on the stop smoking seminars, which usually cost £379. For Hayley, it was a hard-won milestone. “When you think that none of us had any medical or scientific training whatsoever, it’s quite extraordinary,” he says. “We’re sort of inside the tent now – but it took a long time.” As yet, however, the effect is limited. Of a total 317 local authorities in England, so far just 28 have signed up, though the company is in talks to secure more. Quit vaping seminars are also outside the scope of their funding, ringfenced for smoking.

It highlights a growing tension between Easyway and these times. The cornerstone of Carr’s method is that it’s nicotine-free: any attempt to “taper off” with gum, patches or vapes grows the little monster, and prolongs the addition. Health services, however, still promote vaping as a healthier alternative to smoking – even as non-smokers such as myself are increasingly taking up the habit.

To Hayley, it is manifestly preposterous – like nicotine patches and gum, a misguided attempt at “damage limitation”, and proof of tobacco and pharmaceutical companies’ powers to adapt. “It’s not replacing nicotine – it’s maintaining nicotine,” he says. Even if vaping is better than smoking, Hayley adds, “do you really want to remain an addict for the rest of your life?”

Easyway is presently lobbying the government to amend the tobacco and vapes bill 2024 to reflect Nice’s recommendation and require all publicly funded stop smoking services to offer its seminars as a drug-free option. But some experts and campaigners are uncomfortable with Easyway’s hardline objection to nicotine-replacement therapies, particularly now that it is being offered alongside them on the NHS.

Hazel Cheeseman, chief executive of Action on Smoking and Health, said that she wanted to see further evaluation of the Easyway seminars, particularly along equity lines. “Do they work for all groups of smokers, including the most disadvantaged? Do they inhibit people who do not manage to quit with them from using nicotine as a quit aid in future?”

It does follow that, if you fail to kick the habit the “easy way”, you may be less inclined to try the “hard way”. In reporting for this piece, I read and heard dozens of testimonials for Carr’s method. For every overnight transformation such as mine, there were more saying it took at least one attempt for the message to stick, or that it never did. One friend warmly recalled Carr’s metaphors, but admitted she was still indulging the “little nicotine monster”. Gibson said the book spent many years languishing on his shelf before it changed his life. Even Easyway’s former chief executive John Dicey has admitted that the method only sank in after he attended a live group seminar, which he chalked up to his dyslexia: “I could have read the book a thousand times without achieving the tiniest nugget of success,” he says.

But I was most struck by the prevailing tone of gratitude, with people willing to credit Carr’s method even where it didn’t work as billed. I get it: he was someone who wanted to help. Quitting smoking is supposed to be hard. Changing yourself for the better can mean giving up something you love. It is a relief to be told that it doesn’t have to be arduous – that there might even be an easy way.

Photograph by Today/Shutterstock