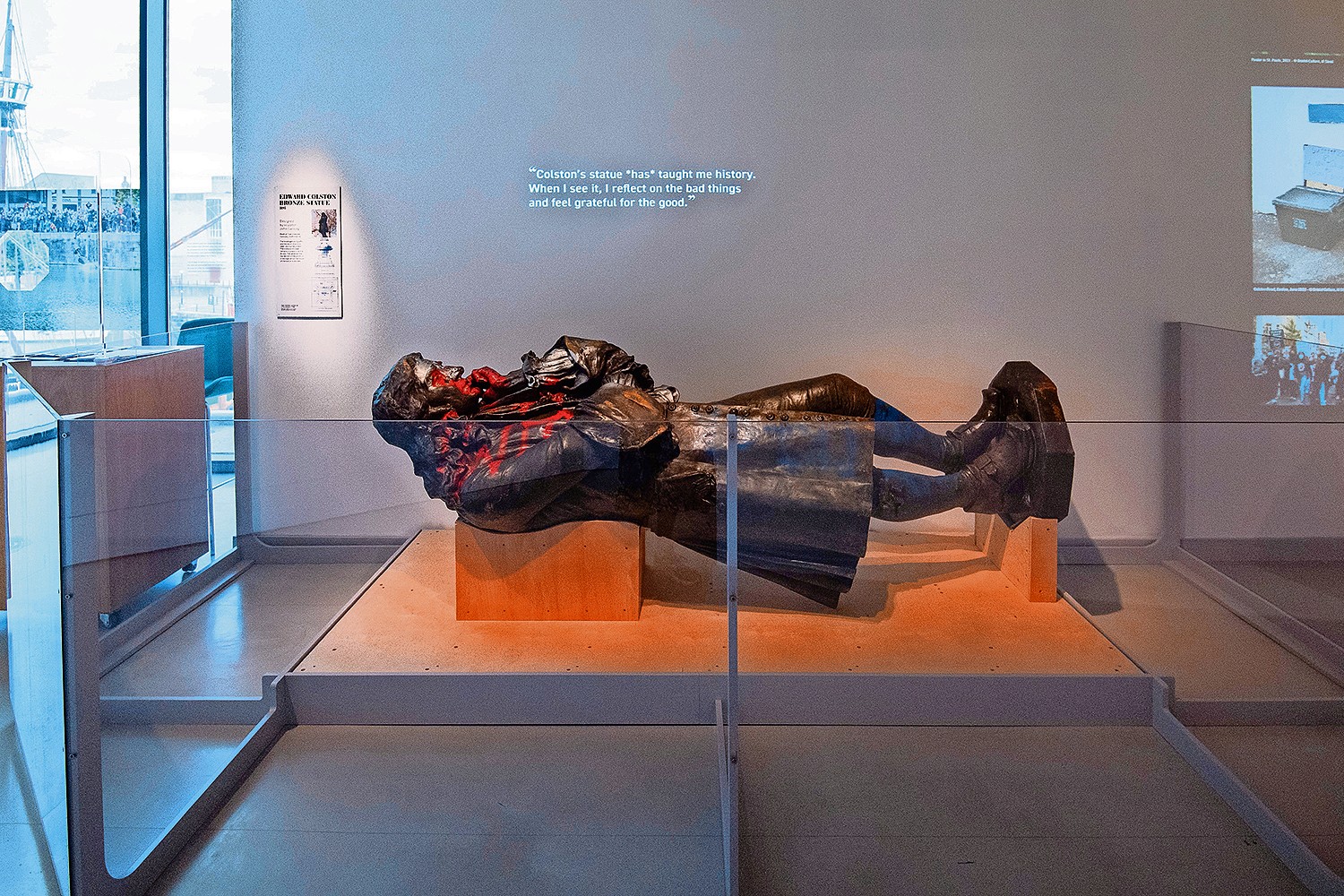

Every Monument Will Fall: A Story of Remembering and Forgetting

Dan Hicks

Hutchinson, £25, pp592

“You can’t,” goes the fatuous and flimsy argument, “rewrite history.” We’ve heard it often enough over the past few years of culture wars, to explain why this or that colonial butcher cannot be removed from a pedestal.

But, as Dan Hicks argues in Every Monument Will Fall, history can and should be rewritten, like science, when new evidence comes to light – the more so when it was previously written by unreliable narrators, motivated by the desire to launder atrocity into enlightenment and suppress the memories of its victims.

This latter is the kind of history with which most people in Britain have grown up, the one that implies that ours is almost exclusively a land of decency, tolerance, democracy, civilisation and ingenuity – and downplays vicious colonial wars, human-made famines and industrial-scale slavery.

It is not to hate your country or to denigrate its genuine achievements to point out its dark sides; it’s just honest. But it still comes as a shock, one with which Britain is only beginning to come to terms, to face just how dark it could be. To quote Mitchell and Webb: “Are we the baddies?” Yes, often.

A silver-trimmed human skull is inscribed with the name of Fox’s pro-Nazi grandson

A silver-trimmed human skull is inscribed with the name of Fox’s pro-Nazi grandson

Every Monument Will Fall sets out to tell this less comfortable history. Hicks is professor of contemporary archaeology at the University of Oxford and curator at the Pitt Rivers Museum, and his previous book, The Brutish Museums, described how many of the treasures of venerable institutions were violently looted.

Now he focuses on the place where he works and on the roles of its founder, Lt Gen Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers, an heir to colossal slave-based wealth, archaeologist, ethnologist, weapons expert and collector of the many thousands of objects that were the basis of the museum’s collection.

He tells stories formed around the life of Fox (to use the merciful abbreviation Hicks chooses of his subject’s name), interwoven with both larger narratives of Victorian and modern history and his own personal ruminations and conversations with friends.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He wants to show the many ways in which the museum’s exhibits, presented as innocent and scholarly, are connected to violence.

He sees connections between Fox’s work on developing Enfield rifles and his later innovations in archaeological techniques. Almost everything in Hicks’s purview seems to be a form of warfare.

Hicks describes the museum’s “Treatment of Dead Enemies” display, removed in 2020, an array of shrunken heads and scalps from multiple locations – intended to show the barbarism of Indigenous South Americans – and compares it with the actions of Lord Kitchener after the Battle of Omdurman in 1898.

In Hicks’s telling, Kitchener had the remains of Britain’s old enemy Muhammad Ahmad dug up and thrown into the Nile, having first had the head removed and sent to Queen Victoria in a kerosene can. Who is the savage here?

Hicks returns repeatedly to a cup made out of a human skull, silver-trimmed and inscribed with the name of Fox’s pro-Nazi grandson, out of which until well into this century members of Worcester College, Oxford, would on special occasions drink. The original owner of the skull is found, with the help of carbon dating, to have been a woman who died around 1788, but unlike the later owners of her cranial fragment she has no recorded name. As Hicks points out, the people who extracted artefacts from their places of origin tend to be identified in museum displays, less so those from whom they were taken.

The book is not a conventional history, nor a straightforward polemic. It’s more ambitious and tangled than that. Hicks is given to flights of metaphor and imagery, to making speculative connections, to atmospherics. One riff links the smile of the Cheshire cat with a “northern hemispheric arc” involving Cecil Rhodes, Berlin and New York. The wide circle of the author’s ire takes in the neo-Victorian beards worn by hipsters.

All this, in relation to the deadly seriousness of the subject, feels self-indulgent. Hicks lives and works at the heart of what might be called postcolonial privilege, which, while not disqualifying him from writing on imperial oppression, surely requires some modesty. Yet he recites the names of Oxford pubs and streets as if everyone should know them, seemingly as sure that the city is at the centre of universe as any old high-table bore. Somehow, those anonymous victims get pushed to the margins again.

What gets missed as a result is the opportunity to address hard and complex issues, and to fully take on some of the counter-arguments to Hicks’s positions. How, really, will all looted objects be returned to their origins, as he proposes? Would it be good to send Afghan Buddhist objects to the tender care of the Taliban, or Muslim Indian treasures to Modi’s Hindu nationalist regime?

Other questions go begging: how, for example, has Hicks managed to work for 18 years at a museum he calls a “psycho-killer hoard”? And is the museum so tainted by the cruelties in its past that it is incapable of being a force for good?

If you want clear conclusions, this is not the book for you. You have to take it on its own terms. It is still a thought-provoking, informative and vigorous read, but it could have benefited from less main-character energy.

Order Every Monument Will Fall at observershop.co.uk to receive a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph by Polly Thomas/Getty Images