The Land of Sweet Forever is a collection of short stories – though really that is too dignified a term for them – from Harper Lee, who died in 2016. You hardly need to be told that Lee’s only novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, was an instant success when it was published in 1960 and has loomed large over 20th-century American literature since. The year before her death, and in somewhat mysterious circumstances, Go Set a Watchman was published. It was described as a “sequel” to Mockingbird, but was written before and is in essence a first draft of her famous, singular book, as her publishers’ records show. Yet it did cast a fascinating and important light on Mockingbird – significantly giving a far fuller picture of Atticus Finch as a man of his time, the kind who would say things like: “Do you want Negroes by the carload in our schools and churches and theatres? Do you want them in our world?” A legion of gen X-ers who named their kids Atticus swooned in horror. Never mind the poor Attici themselves.

The stories in this book, Lee’s biographer Casey Cep notes in her introduction, were found in the New York apartment where Lee lived before moving back to Alabama at the end of her life. Lee was born in 1926 in Monroeville, Alabama; she dropped out of the University of Alabama before graduation and headed for New York: her single acquaintance in that foreign city was Truman Capote, her childhood friend – memorialised as Dill in Mockingbird. She eventually found a job as an airline reservation clerk, squeezing her writing in on the side. Her journey towards To Kill a Mockingbird was given an astonishing boost when two friends gave her a monetary gift equating to a year’s salary, freeing her to pursue her vocation: you can find that story in one of the essays included at the end of this volume, although it’s a tale that’s been told before.

A rejection letter from the New Yorker was discovered among Lee’s manuscripts. I’m not surprised. Reading these fragmentary pieces of juvenile fiction is a little like hearing a young pianist play scales: ask yourself if that is a pastime you’d enjoy. A couple of them arrest our attention with an attempt at the verve she would deploy in the striking opening of Mockingbird: “My friend Sarah Mitchell is having a hard time living with herself these days, and I shouldn’t wonder, after what she did.” (A Roomful of Kibble); “The only reason I did it was because Gerald Gray and his wife are my best friends and I told him I would do it, but I shall never do it again.” (This Is Show Business?) But ultimately these hooks feel forced, overdone.

This is stuff for the archives, not print. It’s not a question of censorship, but quality

This is stuff for the archives, not print. It’s not a question of censorship, but quality

What follows are sketches: a few set in Alabama that hint (with the names used, the kind of scenes depicted) at what was to come; some, set in New York, that strive for the studied 50s nonchalance typified by the likes of JD Salinger. In The Binoculars, an Alabama girl learns to read before her teacher approves the process, a theme that would return in Mockingbird; in A Roomful of Kibble, the narrator (who has made her way from Alabama to New York) recounts an unpleasant friendship to not much effect.

The narrative voice in the latter is unstable; in striving for a comic wryness, the young Lee hits something bitter. This has a more troubling effect in a story like The Cat’s Meow, which attempts to address the racial politics of the day in a way that cannot but make the 21st-century reader squirm. It centres around a man called Arthur, who is working for the narrator’s sister Doe as a gardener. Doe tells the narrator – on a visit back to her native Alabama – that Arthur is a “Yankee Negro … He’s not like any Negro you ever knew before.” The narrative rejoinder seems to wish to express enlightenment: “I refrained from reminding Doe that for the past seven years I had lived in New York City, where among other things more than eight million people enjoy the benefits of democracy.”

Supposed open-mindedness comes across as superciliousness; Arthur’s lack of agency in the tale is awkward, to say the least. The attitudes of the past must not be suppressed or hidden from us, but this is simply not very good writing: stuff for the archives, not for print. It’s not a question of censorship, but quality. Had Lee wished to see these stories published in her lifetime, she no doubt could have published them. But, hey, now she’s gone, there’s money to be made. This is an old story. In the last years of his life, Gabriel García Márquez, who died in 2014, was writing a novel as he struggled with dementia: he told his sons to destroy the manuscript. Instead, it appeared in print as Until August. Some months ago, a book by the late Joan Didion appeared: Notes to John, an intimate journal of conversations she had with a psychiatrist. Clare Reihill – formerly her editor, and who now manages the estate of TS Eliot – expressed her certainty that Didion would never have wanted this material published.

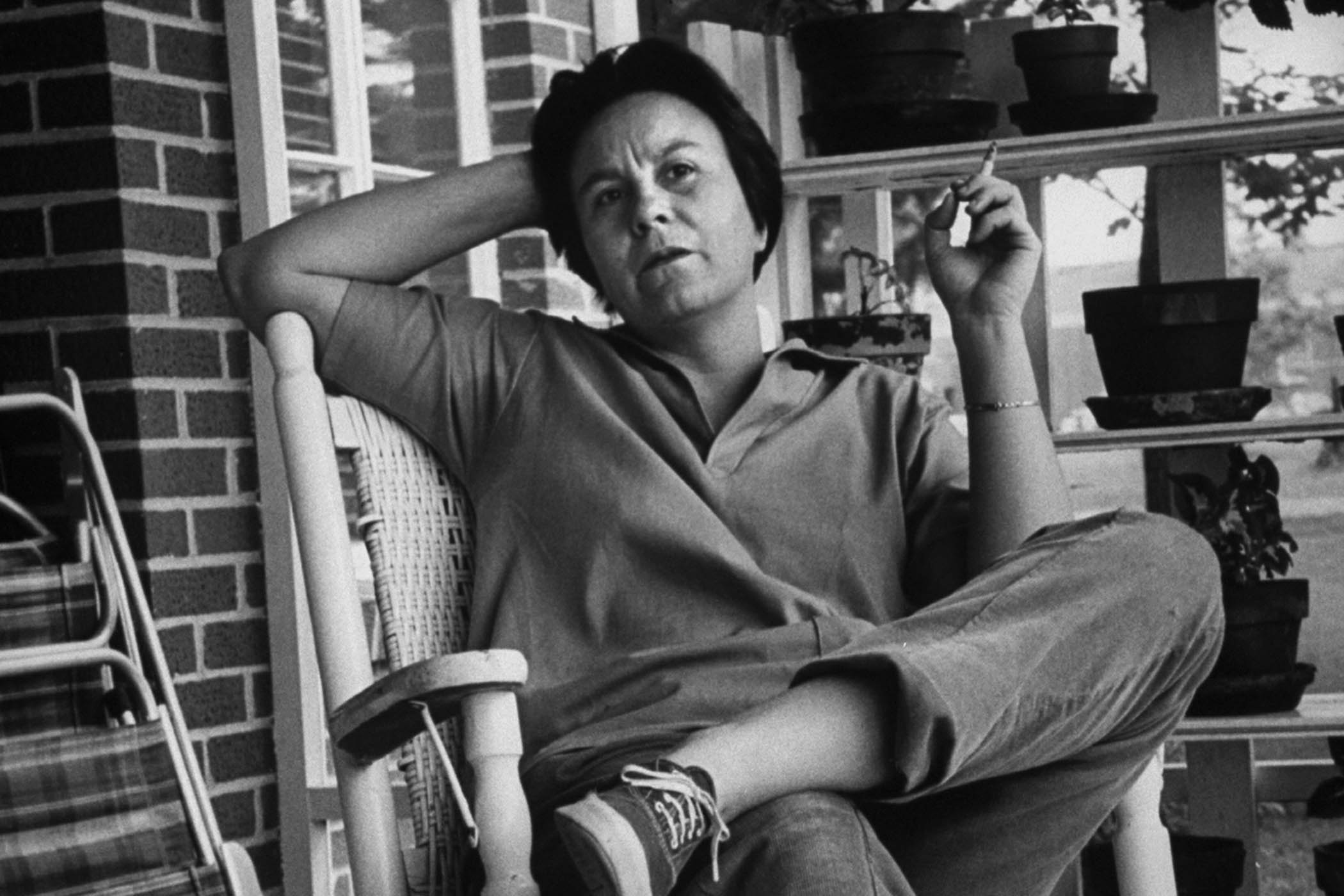

Above: Harper Lee photographed in her New York apartment, July 1960; main pic: Lee visiting her home town of Monroeville, Alabama, the following year.

Lee, I am sure, would be embarrassed by the publication of this book. The only story that works on its own merits is the opening one, The Water Tank, about Abbie, a poor and otherwise disadvantaged teenager who fears she is pregnant: it is an acute and creepy depiction of body horror, of repressive patriarchy, as the girl reacts with terror at her first period and then at what she fears has befallen her. She had an encounter with a boy called Ed, who she describes “with his pants unbuttoned, hugging her”; given Abbie’s ignorance of biology, it was pretty clear to this reader what had occurred, or certainly could have occurred. Yet Cep, in her introduction, dismisses poor Abbie just as everyone around her also has: “The narrator of The Water Tank spends the whole story worrying that she’s about to have a baby, because shortly after getting her first period, she hugged a boy whose pants were down.” This seems to me a shockingly lazy misreading.

The collection ends with a few slight pieces of journalism that, again, hardly deserve the name. The book is padded out by big type, airy leading and slight, vacuous tributes to the likes of Gregory Peck and Truman Capote produced for organs like the American Film Institute or the Book of the Month club. You will not learn anything substantial, or even very interesting, about these folks – or indeed about Lee – from reading it.

Related articles:

Harper Lee was not slight, was not vacuous. To Kill a Mockingbird is an artefact of its time – a white saviour story, as we call it now, and rightly so – but it had its place in moving the arc of history and still does. Lee understood her own significance; it does her a disservice to release this work.

The Land of Sweet Forever by Harper Lee is published by Hutchinson Heinemann (£22). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £18.70. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Getty Images