When Jennifer Dawson arrived to study history at Oxford at the start of the 1950s, she was in for “a great shock”. Dawson was raised in south London in a lower middle-class family of Fabian socialists: her mother was a journalist, her father employed by the Labour-backed Workers’ Travel Association. Dawson attended a state-funded grammar school in Camberwell that, to her, seemed prestigious and elite.

At Oxford, though, she found herself scruffy and strange, a misfit in “a superior kind of finishing school”, she later recalled. Her clothes were wrong. She had no money and, worse, did not know how to behave. “I was suddenly thrown among aristocratic men and women, people who knew how to treat a tutor on equal terms.” It was a place that followed a complex and rigid set of rules, only no one had told Dawson what they were. In her third year, she had a breakdown and was sent to the city’s Warneford hospital. The sex-segregated institution was within an imposing Victorian building at the centre of a wild meadow: in the previous century it was known as the Oxford Lunatic Asylum. She would stay there for six months.

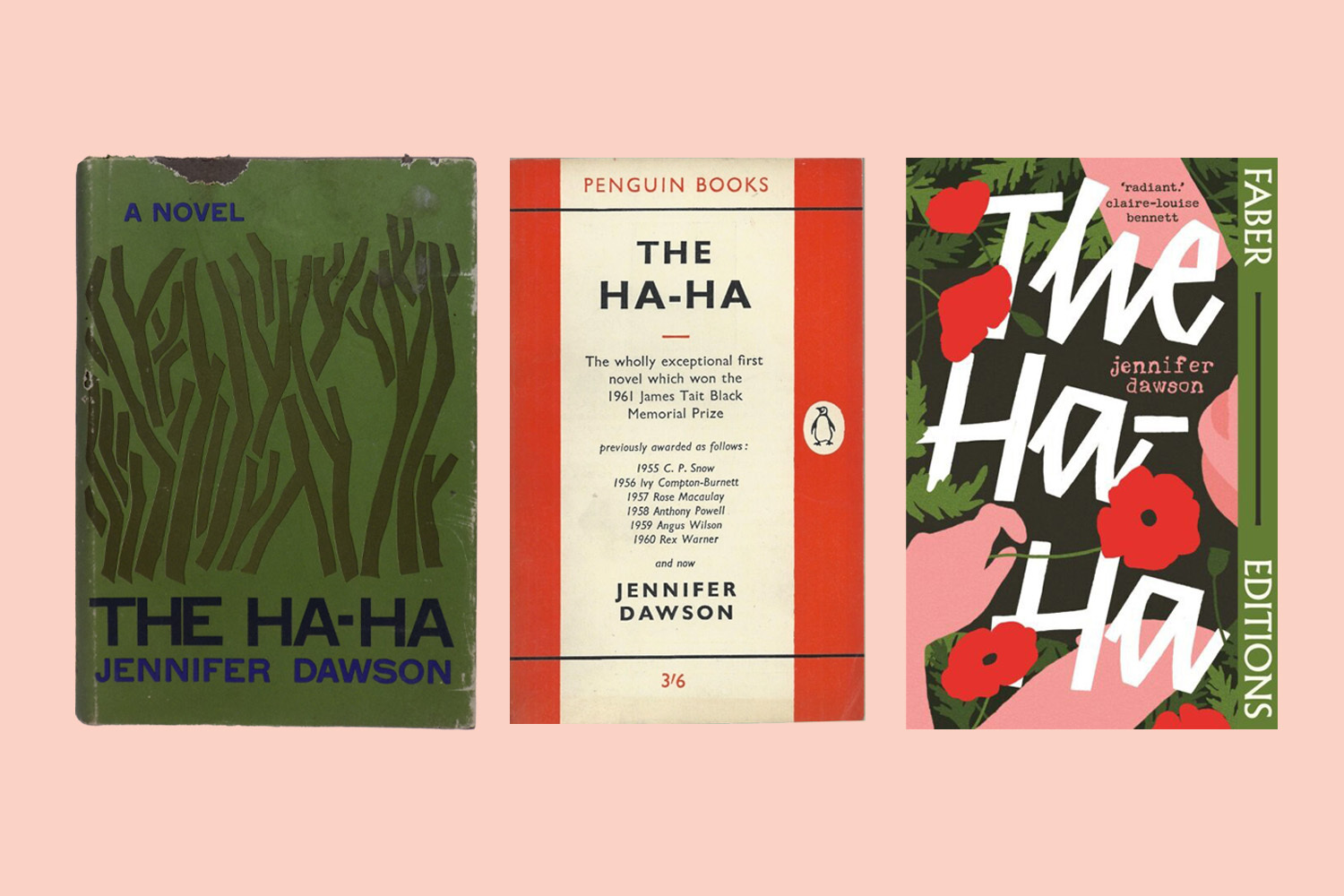

Dawson would return to these experiences of alienation and distress for The Ha-Ha, her short, startling debut novel, published in 1961. It was a critical success and awarded the James Tait Black memorial prize, but over time fell out of print. Now it is reissued in a sleek paperback from Faber Editions. It follows Josephine, an Oxford undergraduate who feels “a little flummoxed, a little behindhand; not quite up to the mark”; the other students are “like good riders who never came off their mounts”. At parties, she is subjected to absurd and disturbing visions of animals – “even-toed ungulates marching through the waste, and files of armadillos with scaly shells, and hosts of big black flies” – as well as bouts of inappropriate, hysterical laughter. It’s the laughter that isolates her from her peers (“I suppose they thought I was laughing at them, and I did not always have time to take them aside and explain”) and, after the death of her mother, leads to her hospitalisation. “The story was really about a girl who did not have the knack of existing,” Dawson wrote, “and the images in it reflected my own preoccupations.”

The novel documents Josephine’s time in a mental hospital – a gothic building surrounded by high grey walls – from summer to winter, and her attempts to reintegrate into society. When we meet her, she has been told she will be “regraded” and assessed for release.

Josephine is an observer – both awed and somewhat alien – and her close readings of her environment are captured in Dawson’s clean, distant style. Nick Hornby described the book’s voice as being “careful, if necessarily neurotic, Oxford prose”, but this belies its strangeness. Josephine’s perspective is distorted, like a Picasso painting. She wonders: “Suppose there were six leopards and six ladies, would you, ought you, to say, ‘12 legs human and 24 legs leopard’, or should one rather say, quite straight and simply, ‘36 legs and six tails’?” At a party, she thinks: “I could see eyes behind Isabel’s, heads moving and twisting, mouths opening and shutting and receiving liquid and savoury biscuit. No one seemed to think it was at all a surprising situation to be in.” Dawson had read Albert Camus’ The Outsider and longed to imitate his blank “white style”: “I would have given anything to catch this tone of voice and carry it through, but I could only steal what I could.”

We see Josephine looking out at the bewildering external world through doors, windows or more unexpected vantage points. At Oxford, she would “pass underneath the lighted windows of colleges and big houses” and glimpse “the talk, the arguments, the clink of glasses, the shadow of bare arms, and smooth sculptured heads”. From her hospital bed, she watches nurses hover in “the twilight of the dark green corridor” beyond; in her room, she sits at the windowsill, looking at the geraniums outside. When she is “placed”, working in the home library of the retired Colonel Maybury and his wife as a first step towards “rehabilitation”, she stares at the busy redbrick street below, a cluttered mix of colour and pattern. Her few positive interactions with others happen at a remove: through a doorway, or the window of a car.

People ask how she is feeling about “the big impersonal world outside”. Josephine prefers it from a safe distance. The party of an old classmate immerses her in a world of horrors: “The music blared and stopped. Faces popped on and off like lamps. Mouths clapped up and down; words shot in and out, but the room full of people seemed to have escaped me … each time my turn came to lay a contribution I found myself catapulted into this empty space in the middle of nothing.” Dawson is attentive to the way such experiences exist on a spectrum between ordinary human distress – who among us has not felt this sort of terrible, unsettling alienation and insecurity amid a party of strangers? – and a more fundamentally destabilising internal fracture, and how easily one can give way to the other.

Josephine spends her days at the Mayburys’ and her evenings hiding out at the edge of the hospital, lying in the ha-ha – a grassy ditch – along its boundary walls, watching birds wheel against the sunset. When a patient, Alasdair, jumps down to sit with her, she notes: “I’ve lost my view.” Here, Josephine is invisible, while all is visible to her. It’s a place where, in the space between sanity and insanity, she can be completely overlooked, as if she has slipped through a crack and disappeared.

Dawson was writing in 1960, a year after the 1959 Mental Health Act was passed and amid a shifting conversation around mental illness in Britain: the institutionalisation of those with mental health issues seemed increasingly inhumane. Dawson had not yet read RD Laing’s 1960 work The Divided Self, which posited that madness might be a response to external pressures, when she started The Ha-Ha. It was written, she later reflected, in the “loophole between this Act of Parliament and the libertarian mental health movement of the mid-60s and early 70s where voices grew louder as they suggested that physical treatment, the pads and cooling-off rooms, locked doors, and even drugs and informal, voluntary confinement of the mentally ill were sociopolitical violence against the real, nonconforming voices of our under-societies.”

Her scepticism of such liberal positions here is palpable. Yet Dawson’s novel prefigures many of these ideas, laying bare the brutality of institutionalisation; the mental hospital’s role in tidying away inconveniently disruptive individuals; the cruelty of forced electroconvulsive therapy and lobotomies; the expectation on female patients to be acquiescent and unquestioning to earn their release. (“‘Play the game, Josephine,’ fellow patients insist. ‘Keep the rules and you’ll get well!’”). Alasdair mocks the “rehabilitation” practice of dances in the recreation room: “‘It’s like watching the Titanic,’ he chuckled, ‘with the band playing as the jolly old ship goes down.’” He can’t understand why Josephine isn’t angrier. “‘All those deteriorated men and women,’ he went on, ‘being pushed about to satisfy the sadistic instincts of the male nurses and social therapist, shouted at and wheeled about like children … Do you never want to rage at the whole bag?’”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Even contemporary mental health cliches are present. A nurse repeatedly reassures Josephine not to feel ashamed, in the language of today: “If you had come here because of some injury to your leg or arm you would not be made miserable.” To Josephine, these “condoling, cajoling” words are hollow. “She would … remind me that mental illness is just like bodily illness, forgetting that the mind is not at all like the body, but the very opposite.”

In the late 50s, after her own recovery, Dawson worked in a mental hospital. The pressure patients felt to act “sane” was clear to her and her colleagues, who saw how male doctors “felt the test of psychiatric cure was whether the patient was fitted back neatly into his (usually her) unquestioned slot in an uncriticised semi-detached society”. Dawson read The Fear of Freedom by Erich Fromm, which considered conformity a deadening defence mechanism. Fromm later argued in The Sane Society that “a whole society can be sick”; that those who seem insane are people “of greater integrity and sensitivity … incapable of accepting the cultural opiate”. Dawson remained cynical of this theory: her own experience of mental distress could not allow her to idealise it. She would later insist she “was lucky to have written The Ha-Ha before being influenced by the ideas of the mid-60s. The high and prophetic status of insanity, neurosis and cold misery will continue to be questioned by those who have actually experienced it, nursed it, or seen people they love succumb.”

It is possibly the last book Sylvia Plath ever read, on the weekend she died

It is possibly the last book Sylvia Plath ever read, on the weekend she died

Dawson was introduced to philosophy at Oxford in her tutorials with the novelist Iris Murdoch. (Dawson remembered Murdoch as “marvellously eclectic”; others recalled she would stand on her head while teaching to “liven things up”.) When Dawson wrote The Ha-Ha, she had left her job at the hospital to study philosophy in London, and the 60s were just beginning. (“The shock of Rachmanism … Lady Chatterley’s Lover found to be suitable reading for women … Samuel Beckett not yet trendy,” she wrote.) One night, she attended a party at a flat overlooking Regent’s Park and heard the sounds of the animals at London Zoo mixing disconcertingly with the noise of the room. Though Dawson had resolved not to write more fiction after a previous novel had been roundly rejected, The Ha-Ha “leaked out after a couple of terms at London, like faulty plumbing”.

If that word “leaked” suggests something uncontainable and confessional, it’s perhaps not surprising the novel is often compared to Janet Frame’s Faces in the Water (1961) and Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar (1963). It certainly shares those books’ detachment and irony; their clever, observant narrators undergoing escalating mental health crises and hospitalisation; their awareness of societal and institutional injustices. In fact, The Ha-Ha was possibly the last book Plath ever read. According to her biographer Heather Clark, she was reading it the weekend she died, in February 1963, weeks after The Bell Jar had been published – to a more lukewarm reception than The Ha-Ha. Clark writes that Plath “likely suspected there was only so much room” for novels like this and that “hers, it seemed, was a year too late”. Today, Plath’s novel is the more famous, more influential one. But decades later, both books still burn with a cool flame.

Dawson went on to write several more books, but, 25 years since her death in 2000, The Ha-Ha remains her most significant and timely work. Towards the end of the novel, Josephine watches a doctor force a woman to receive shock therapy after she accuses him of denying her discharge. After months of being unable to feel anger, Josephine is suddenly indignant:

I crept out into the gardens for the first time outraged … It was cold outside, and when I stood under the beech trees and heard the sounds of music coming from the recreation room I remembered that it was the Titanic going down. There they all were, old ladies in print pinafores and pink hair-ribbons, old men in carpet slippers slunk back against the walls, while the social workers shuffled them about, dragging them to their feet to do the ‘Conga’ … as I heard the social workers’ shouts and the obedient shuffling of many feet, and thought of coming to terms with my existence, it seemed that something was coming out of that room to destroy me. There was before me the Mayburys, and then some other place, safe and quiet, not making too many ‘emotional demands’ or bringing me into contact with anything that might remind me that I was alive. It was death. I was being smothered to death.

But Josephine refuses to die. Beneath the beech trees, she turns towards one trunk, and bites it. “I stuck my teeth into the dusty, smooth bark of the tree. I ran my mouth up and down it searchingly, and cried and cried: ‘I am alive, aren’t I? Aren’t I, even if I don’t know the rules?’”

The Ha-Ha by Jennifer Dawson is published by Faber Editions on 31 July (£9.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £8.99. Delivery charges may apply

Photograph portrait by Cynthia Bradford