My connection with Albania is both marginal and singular. I’ve never visited, but in 1985, unbeknownst to me, my second novel, An Ice-Cream War, was pirated and translated into Albanian. I only know about this because a friend and fellow novelist, Brian Aldiss, who was travelling in Albania at the time, spotted a copy in a bookshop in Tirana. He bought a copy for me as a souvenir but inadvertently left it behind in his hotel. Tantalisingly, the book clearly existed but I’ve never seen it and I’ve never been able to track down a copy. It’s almost like a phantasm. The Albanian version of An Ice-Cream War remains the rarest edition of anything I’ve ever written.

This anecdote chimes perfectly with the bizarre and shifting world described in Lea Ypi’s remarkable account of the life of her grandmother, Leman Ypi, in Albania in the mid-20th century. Leman was born in 1918 in Salonica (AKA Thessaloniki), Greece. Her family were part of the Francophone bourgeois Albanian diaspora, and Leman would return to their homeland in 1936, after she had turned 18. The self-appointed monarch, King Zog I, was on the throne and, in this interwar period, Albania enjoyed a strange kind of Ruritanian independence, although economically it was heavily dependent on Mussolini’s Italy. A largely rural community with vast estates controlled by all-powerful local “Beys”, the country possessed an intelligentsia, there was a free press, and the middle classes had aspirations to participate in what one might term the Europeanisation of the Balkans.

This is the Albania where the young Leman found herself. But then history took over. Italy invaded in 1939, declared the country a protectorate, and King Zog was deposed. He fled into exile, to a suite in the Ritz in London, taking a large chunk of the country’s gold reserves with him. After the trauma of the second world war and the Nazi occupation, Enver Hoxha turned the country into a hardline Stalinist regime, and Leman’s relatively comfortable existence as a wife, mother and state employee abruptly changed. She was perceived as a security risk (she was believed to be working for the Greek intelligence services) and persistently harassed and surveilled; her husband, a senior government official, was imprisoned. Everything began to fall apart.

Lea Ypi, a distinguished academic and professor of political theory at the London School of Economics and the author of Free: Coming of Age at the End of History, attempts to track the course of her grandmother’s life through the upheavals of the 1930s, 40s and 50s in Indignity: A Life Reimagined. The prologue opens with the author visiting the contemporary Albanian archive in Tirana (with the wonderful appellation of the Authority for Information Concerning Documentation of the Former State Security Service) to see what authenticated traces might remain of her grandmother’s years in Albania.

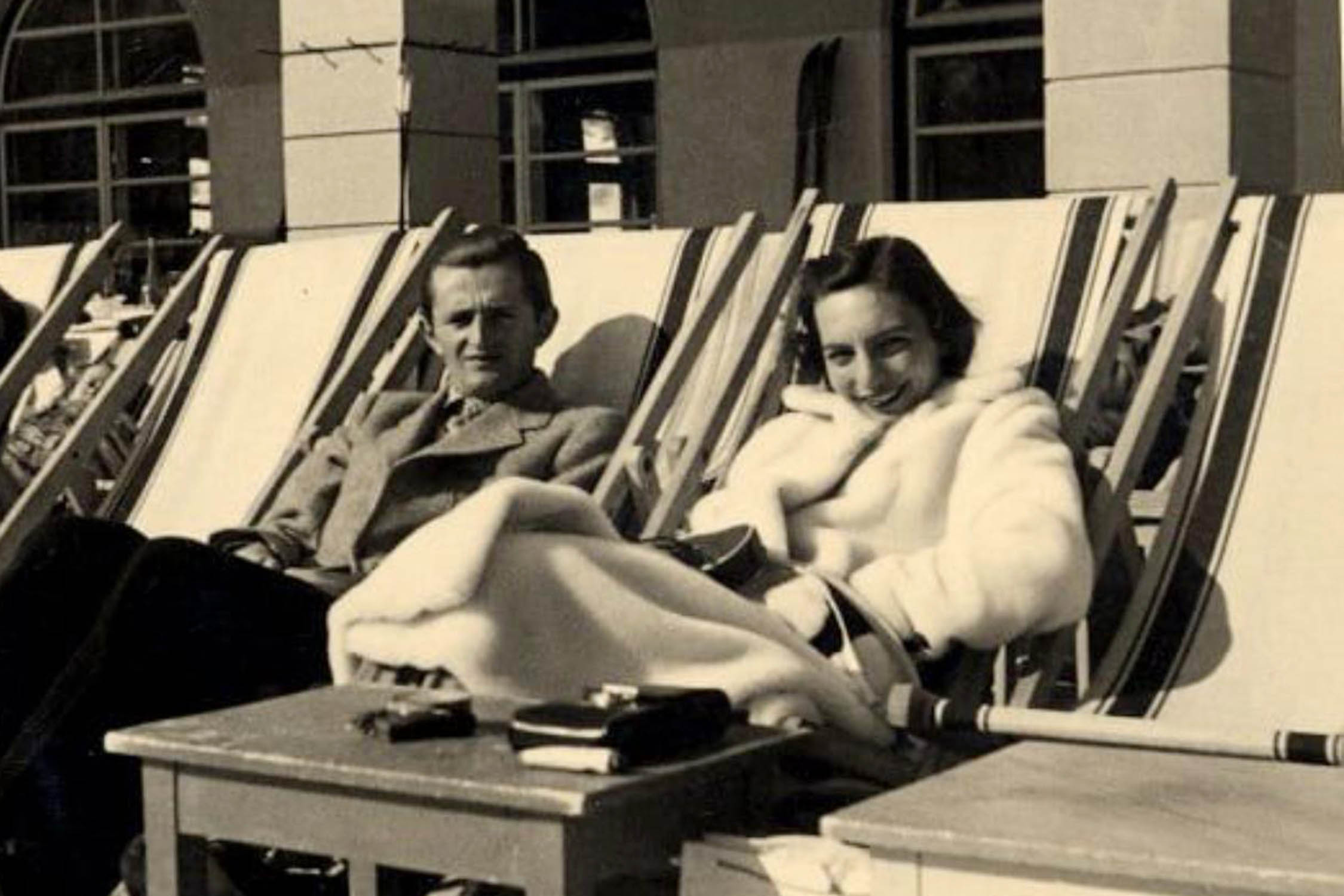

She was prompted in this endeavour by the chance sighting of a photograph she had never seen before on a stranger’s social media page, showing her grandmother Leman and grandfather Asllan on their honeymoon in Cortina, Italy, in 1941. Staring at the photograph – contemplating the young, glamorous couple – she tries to imagine what they must have been feeling and experiencing while all around them the second world war was taking place in all its malign dimensions. “Imagine” is the key word here – also signalled in the book’s subtitle – and is the motive that prompts Ypi to depart from orthodox historical reportage and biography. With only scant physical evidence, and her own memories and intuition, Ypi “novelises” her grandmother’s life and marriage. These sections of the book are freely recreated with reported dialogue and all the subjective interiority that a novelist has at her or his disposal.

Initially, I thought this might be a misstep. There’s a lot of exposition to deal with – historical, familial and personal – and putting it into dialogue or inner thoughts can sometimes seem very stiff and unnatural, not to say baffling:

Eleftherios had made a catastrophic mistake in accepting the Turkish government’s argument that Greek properties in Asia Minor were worth far less than Muslim properties in Greece. Now everyone was paying the price, and everyone was angry.

However, Ypi’s distinctive methodology begins to win the reader over. She flashes forward to her continued and frustrating research in various archives and museums, before returning us to the novelised past. The text is interspersed with so-called intermezzos – selected extracts from official documents (set in a different typeface) – that cast a light on the developing narrative. The book emerges as a clever hybrid, happily exploiting all the many possibilities of telling a life story. In the process, not only is the life of an individual described and plotted with great success, but also, at the same time, a form of oblique history of 20th-century Albania is offered, illuminating all its perversities, absurdities and ruthlessness: Hoxha emulated Stalin in his paranoia and his purges.

Leman survived, but her husband spent almost 15 years in prison, and the couple managed to live on in Albania – in difficult circumstances – until Asllan’s death in 1980. Their son, Zafo, would eventually father Lea. She came to know her grandmother well – and this closeness stimulated the urge to discover the details of her story.

‘Imagine’ is the key word here, as Ypi departs from orthodox historical reportage and biography

‘Imagine’ is the key word here, as Ypi departs from orthodox historical reportage and biography

But there was a final twist waiting at the conclusion, almost Kafkaesque in its eeriness. Lea came across an official death certificate asserting that her grandmother had died in 1972. A physical impossibility. It turned out – quite extraordinarily – that, contemporaneously, there had been another woman in Albania called Leman Ypi whose life had uncanny parallels to those of Lea’s grandmother. However:

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Unlike my grandmother, this stranger, this other Leman Ypi, has no granddaughter who can record that life, nobody who can reflect on the meaning of her dignity. And yet, that life surely deserves to be recorded somehow.

The measure of this regret explains the title of this beguiling and moving book. Ypi has tried in her complex, fractured narrative to restore a sense of dignity to her grandmother’s rackety, alternately cursed and fortunate, history-buffeted life. At the end of the book, the author speculates that “Perhaps this is the ultimate meaning of being human: remembering the dead in the right way.” In this regard, she has triumphantly achieved her objective.

Indignity: A Life Reimagined by Lea Ypi is published by Allen Lane (£22). Order a from The Observer Shop for £19.80. Delivery charges may apply

William Boyd’s new novel, The Predicament, is published on 4 September by Viking

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photograph of Leman and Asllan Ypi, on their honeymoon in Italy in 1941, courtesy of the author/Mihaela Noroc