Something has happened in the world of migration and asylum that is epochal and quite possibly irreversible. In the 1970s, there were wars across Asia and Africa – Vietnam, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Nigeria, Israel, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Sudan – to name just a few. Many millions died and scores of millions were displaced.

Yet the migration routes that run today through Turkey and Libya were scarcely used, except by European hippies going in the opposite direction. Of course, refugees did arrive in the UK – 28,000 Ugandan Asians expelled by Idi Amin arrived in 1972-3, their status already established.

In a globalised world, the situation is radically different. Very few western travellers now risk cross-border travel by road in Asia and Africa, but the migration of those fleeing wars (arguably not as prevalent as the 1970s), political repression and from poverty (ditto) is an enormous illicit business that ends, as far as the UK is concerned, with small boats crossing the Channel.

It’s an arduous and often perilous journey, but more than 150,000 people have made it since 2018, when the small boat crossings began in earnest – one of the effects of Brexit that its proponents have quietly disowned.

Whether you see this movement as one of illegal migration or humane asylum, it is a highly emotive political issue that has helped galvanise support for the Reform party. In his new book, We Came By Sea, the memoirist and travel writer Horatio Clare sets out to challenge the popular narrative of “fear”.

The book’s title is misleading because the “we” suggests its focus are those who make the crossing. In fact they seldom enter the story directly, remaining mostly idealised projections – noble, courageous but essentially other. His real interest is in all those who help secure their safety in the UK – from charity workers in Calais to RNLI rescuers on the coast to Citizens Advice volunteers around the country.

In some ways, the agencies seeking to help have been co-opted into this nefarious trade

In some ways, the agencies seeking to help have been co-opted into this nefarious trade

They are all part of what Clare argues is a glorious rescue mission to rival Dunkirk, and one that has been neglected by the media in favour of scaremongering. There’s something to that, and a moral correction is a worthy endeavour. But this is an impressionistic polemic written in a highly romantic style, full of righteous anger and adjectival flourishes, that skirts the knottiest political realities.

If Britain was simply divided between decent compassionate people who want to welcome and help migrants and asylum seekers, and nasty racists who prefer to spread hate and misinformation, then the debate would be satisfyingly straightforward. Alas, the issue has been ill-served by such false dichotomies.

Related articles:

Indeed, it has become such a polarising subject that it’s now a kind of provocation to state that the people within the boats are fleeing from… France. A large, ruthless and highly profitable criminal enterprise is in operation to convey mostly young men from one democratic nation with a legal obligation to accept refugees to another. And, like it or not, in some perverse way all the agencies seeking to help have been co-opted into this nefarious trade in people.

What’s the answer? Clare and the volunteers he interviews call for safe and legal routes for those with strong asylum claims. This, in tandem with border enforcement, according to a Refugee Council report, could work. But there’s no reason to believe that the people with the strongest asylum claims are those who congregate on the French coast waiting for smugglers to ferry them into the hands of rescuers. A scheme to resettle Afghans failed to stop those not accepted from taking to the boats. And what would effective border enforcement look like, when all such current measures Clare subjects to harsh criticism?

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Because demand far exceeds supply in asylum resettlement, any lowering of obstacles will inevitably increase numbers. The current system is hugely expensive and rewards those with money to pay the smugglers, as well as the private companies that guard and house them, but any alternative must address what motivating effect it has on all those wishing to secure asylum in the UK.

Clare seems to argue that anyone who expresses a strong affinity for Britain should be admitted, though he thinks those people are ignorant of the hardships of the asylum process, the bad weather and poor food – as if none have a mobile phone and have never spoken to successful claimants.

In any case, he stresses, legal migration is far greater, so why the fuss about the small fraction of so-called illegal migrants? One difference is that those who gain asylum must be housed by local authorities that are already struggling under enormous housing demands.

As Clare notes: “15,000 people are waiting for affordable homes across Liverpool. Placing asylum seekers in the poorest communities, which is routine because it’s cheaper, guarantees hostility.”

Is the solution to place them in wealthier communities, in better, more expensive housing? He doesn’t say, but as with so much concerning this issue, there are certainly no easy answers.

We Came By Sea by Horatio Clare is published by Little Toller Books (£20). Order a copy from observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer (ends 11 June). Delivery charges may apply

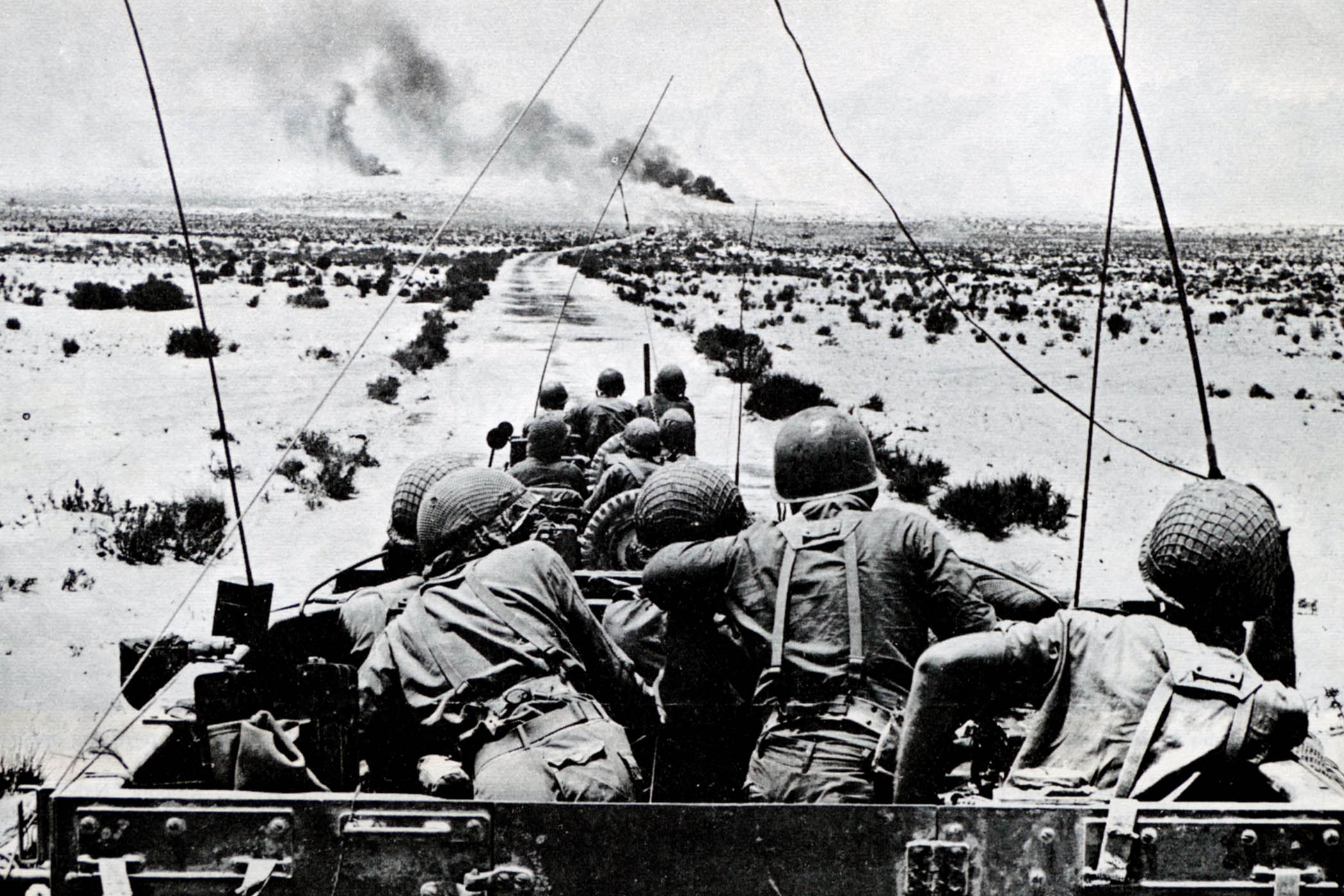

Photograph by In Pictures/Getty