Related articles:

William Shakespeare knew the value of a good book. Prospero, in The Tempest, prized his private library “above my dukedom”.

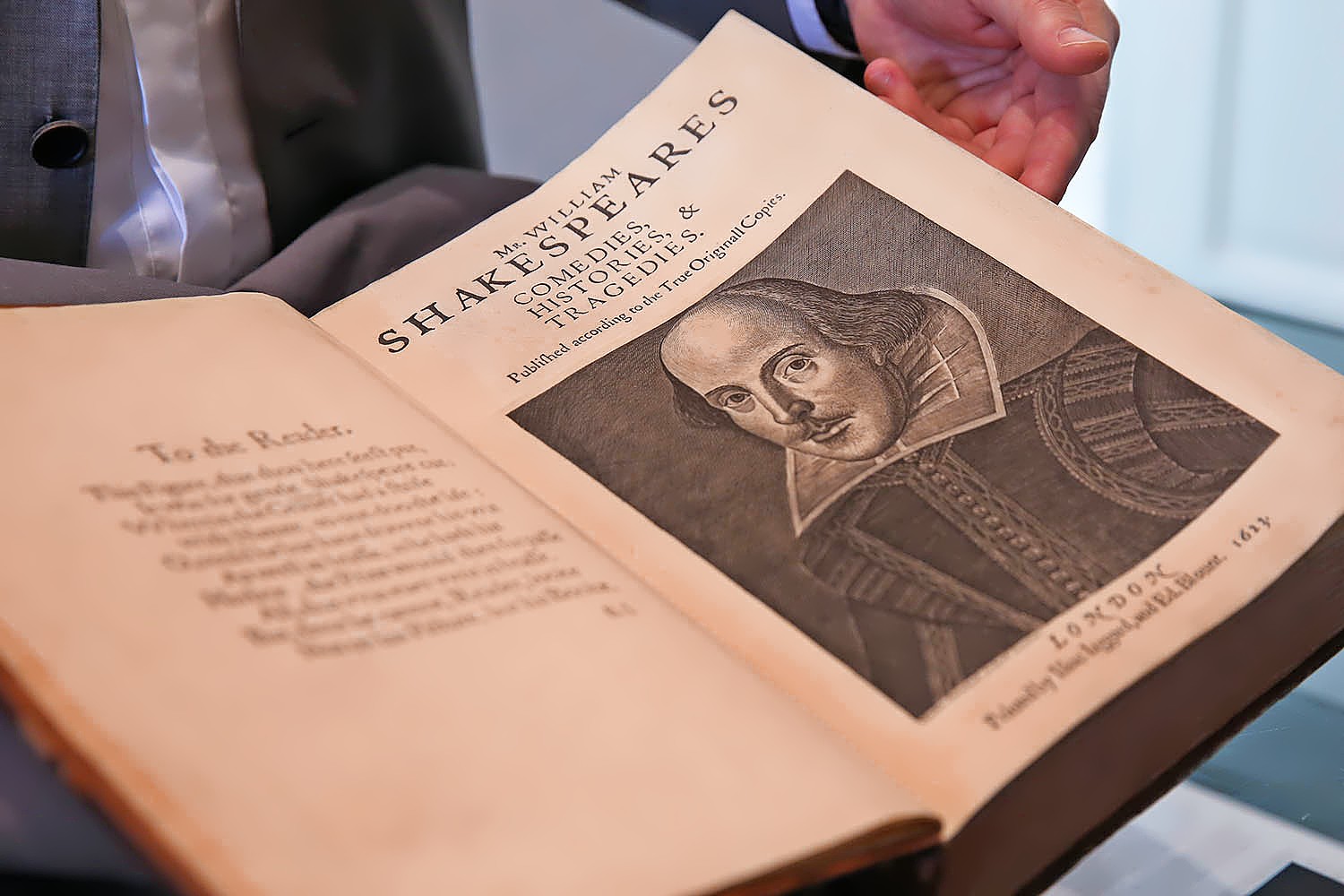

Ever since the first anthology collection of Shakespeare’s plays, known as the First Folio, was published in 1623, collectors have been queuing up to purchase a little of Prospero’s magic. The First Folio ensured the survival of several Shakespeare plays that had never been published individually, The Tempest and Macbeth among them. Of the 750 copies printed, we only know for sure of 235 remaining.

Excitement soared when Sotheby’s announced the upcoming sale of “a set of all four of Shakespeare’s Folios”: a First Folio, alongside updated editions published in 1632, 1664 and 1685. Sotheby’s advertised these as a “complete set”, last offered as a single auction lot in 1989.

Yet a funny thing happened when I rang Sotheby’s and started asking questions on behalf of The Observer. The auction, I was suddenly told, had been cancelled. The listing was scrubbed from the website; the “set” had been privately sold.

This may be cockup rather than conspiracy: two antiquarian sources suggested to me that the private sale had been in the works for some time, and that “the sale should never have been announced” publicly. At last week’s London’s Rare Books Fair, where Stephen Fry and Graham Brady were among the men in suits queuing outside the Saatchi Gallery, the gossip was of furious collectors outmanoeuvred by a megabid.

There were some sneers, too, at Sotheby’s describing these folios as “a complete set”: each anthology was published separately at a different moment in book history. They have been sold together in the recent past, if not “in a single lot” – the promised Sotheby’s twist.

When I speak to Donovan Rees, books and early manuscripts specialist at the bookseller Bernard Quaritch, he concurs: “There’s not really any such thing as a set of Shakespeare folios, because there’s not going to be any single buyer who would have acquired them between 1623 and 1685.”

The global excitement over the sale, however, still speaks to our fetish for tangible Shakespeare relics. It has also offered an accidental window on the dark side of antiquarian bookselling: the regular disappearance of important volumes into the private collections of the wealthy.

Related articles:

This isn’t a new phenomenon. The folio has always been a luxury item, especially compared with the cheap “quarto” editions of individual plays published in Shakespeare’s lifetime. Some of the first purchasers of the 1623 folio, seven years after Shakespeare’s death, bought it to pad out showcase libraries of high-status texts, as Oxford’s Prof Emma Smith demonstrates in her landmark study Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book. It is not a portable book.

When I do speak to Sotheby’s in-house expert, the erudite Dr Gabriel Heaton, he points out that Shakespeare’s folios have a long history of readership in private hands. Some collectors relish scholarly engagement: the American lawer and banker Robert S Pirie cherrypicked academics to view his luxuriously displayed New York collection. But when he died, in 2015, his $15m library was auctioned off by Sotheby’s rather than donated to worthy institutions.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Smith emphasises that “scarcity” isn’t a driving factor in price. First Folios do become available regularly. By contrast, of the 21 surviving complete copies of the Gutenberg Bible, none have come to market since 1978. Elsewhere, Smith has argued that “to collect may always be to sacralise”. At London’s Rare Book Fair, you could purchase nine pages of the Third Folio for $19,500, as much for the luxury “morocco” binding as any novelty in the contents.

There is still danger in selling off history. When I speak to Prof Henry Woudhuysen, former rector of Lincoln College, Oxford, he observes that there’s still plenty we don’t know about the folios, which may now be lost to research.

“I’m not sure this copy of the First Folio is known about or has been described in the last 20 years or so, so it’s disappointing if that copy of the folio may not be seen again for another 20.”

The third and fourth were published much later but still have plenty to tell us about book history, Woudhuysen tells me – except that “no one has done that work yet”, and with every private sale a little more access to the record is lost.

How distressed should we be? I’m persuaded by Smith’s case that the physical books we fetishise teach us more about shared political values than love of literature. (I demur at her suggestion, in her recent book Portable Magic, that we should be less bothered by political book-burnings.) When folios carry the marks of their readers, they become special: my hardened scepticism about the dodgy “Second” folio melted when I was treated to a viewing of Charles I’s copy, complete with annotations made by a king facing death.

But there are plenty of these folios around. If a millionaire wants to hoard a private copy, good luck to them. The rest of us still have Shakespeare’s words. They are his living legacy.

Photograph by Dinendra Haria/Getty