This year marks 20 years since the publication of Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go, inspired, as he commented in a recent essay, by the ethically controversial cloning case of Dolly the Sheep. (Dolly was later euthanised, which has sombre overtones for the work under review.)

Catherine Chidgey is a prodigiously talented New Zealand author, whose latest novels range in topic from Buchenwald concentration camp (Remote Sympathy) to a problematic, charismatic teacher at a 1980s primary school (Pet) to The Axeman’s Carnival, narrated by a talking magpie. “Each book is such a different creature,” Chidgey has said, but what her fiction has in common is the theme of outsiders and the insidious dangers of othering.

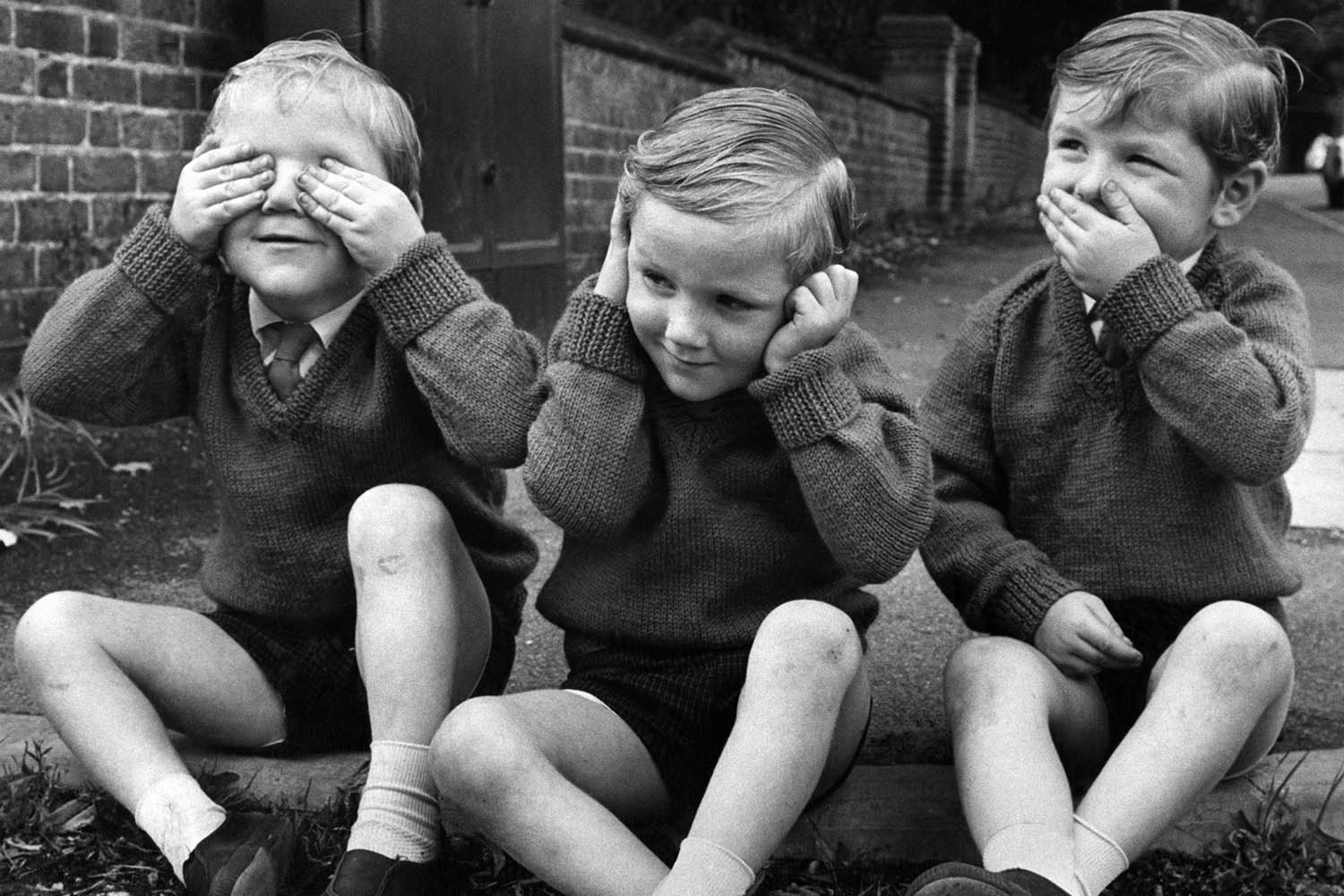

Like the Ishiguro novel, The Book of Guilt is set in a dilapidated children’s home, with its isolated inhabitants deliberately cut off from the outside world, approaching adolescence and beginning to doubt all they have been told of their lives so far. Identical triplets William, Lawrence and Vincent (the novel’s principal narrator) are the sole remaining residents of Captain Scott’s, a large “bone-white” mansion on the edge of the New Forest. They are cared for in shifts by three “mothers” – Mother Morning, Mother Noon and Mother Night. Every day their dreams are recorded in The Book of Dreams, their mishaps and peccadilloes as crimes in The Book of Guilt. To differentiate, each is assigned their own clothing colour: red for troublesome William, green for sensitive Lawrence, yellow for pragmatic Vincent. They are taught from The Book of Knowledge, dusty volumes of children’s encyclopedias, from which they recite, parrot-fashion, in a manner that is oddly charming and yet uncomfortably prescient: “When we burn coal, we’re burning the sunshine of long ago.”

The children are fed a daily cocktail of pills and injections to ward off a so-called ‘Bug’

The children are fed a daily cocktail of pills and injections to ward off a so-called ‘Bug’

Some of the encyclopedia’s pages, however, have been torn out. The children are fed a daily cocktail of pills and injections to ward off a so-called “Bug”. The medicine gives them strange rashes and fevers. During their few outings to the local village they are shunned.

It is 1979; the first female prime minister is in power. Under her government their particular set-up – part of the postwar Sycamore Homes scheme – is to be dismantled. While the familiar icons of a 1970s childhood such as spirographs and Stickle Bricks are much in evidence, in this alternative history the war ended in 1943 with the Gothenburg Treaty. Other children from the Sycamore scheme have already gone as a special “treat” to the faded seaside town of Margate and never been heard from again. The triplets themselves are to be “rehomed” into the community, their availability advertised in shiny brochures, a plan presided over by a Minister for Loneliness – a poignant and lovely touch from Chidgey.

In their joint dreams appears a girl, running through a forest, uncannily similar to the main character in the novel’s parallel narrative, that of Nancy, also 13, living with her parents in a bungalow in Devon. Nancy is cosseted and adored. She is also never allowed out of the house, or to mix and play with other children.

Chidgey’s luxurious, unhurried prose stokes tension in a compulsive thriller with macabre hints at historical cases of scandalous cover-ups, unprincipled drug trials, eugenics and ethnic cleansing, genetic experimentation. (Nancy’s desperate letter to Jimmy Savile’s wildly popular Jim’ll Fix It TV show at a crucial point in the story is an indicator of how children are taught to automatically trust adults – whether in personal or public life – and how adults can wield terrible power over children.)

This instance, along with numerous others, carries sordid memories of some of the UK’s most notorious serial killers and abusers. Yet there are saviours too – a politician who refuses to play the game and pays for it with their career; a carer who rebels to warn Vincent about the consequences of “Margate”.

The revelations exposed in The Book of Guilt are collective and shaming. Above all the novel is a powerful recreation of an off-kilter Britain at the end of the 1970s – looking back at the horrors of the second world war with the talons of the worst aspects of Thatcherism about to be unsheathed. It feels scarily momentous.

The Book of Guilt by Catherine Chidgey is published by John Murray Press (£20). Order it at observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photograph by Mirrorpix/Alamy