Related articles:

While the butterfly effect has taken flight in popular culture, which is replete with cinematic takes on chaos theory, Simon Armitage’s New Cemetery dwells in the dust of the moth effect. In his first full-length poetry collection since The Unaccompanied in 2017, the poet laureate and former probation officer makes a marvellous if macabre return (think pickled cadavers and putrid intestines) with a celebration of mothy chaos – “funeral confetti”, as he christens the flutter of fibrous wings that cloud graveside tealights and choke the throat like grief.

As Armitage explains in a detailed preface, even moths that “dress in the extravagant ball gowns and smoking jackets of their showbiz counterparts the butterflies” trail “drab and duller” in their cousins’ shadow. Yet when a series of cow fields are converted into a cemetery near the poet’s home in Huddersfield (the locals are “not charmed”, but he likes the quiet), coupled with the sudden death of his father in 2021 (prompting him to make his “peace with the dead”), this supposedly humdrum insect undergoes, for Armitage, a drastic transformation, from understudy to unlikely hero.

Armitage, who used his laureate’s honorarium to create the Laurel prize for environmentally themed poetry, run by the Poetry School, reminds us that moths are vital “indicator species” that warn about “the health of the insect population particularly and the wellbeing of the natural environment in general”. Their “scarcity is ominous” and signals “death within nature” itself.

It takes the sensibility of an exceptionally skilled poet to parse the “hypnotic intricacy” of a moth’s patterns as “codified alphabets or pictograms [...] flagging messages of alarm”, or as “folded pages / of veiled script” bringing “word / from the dead”. Yet the wing-beat of his words, powerful and precise (lines such as “Time – what else – / propped in a corner / like a cricket bat” hit you with an unexpected force) carry the echo of Armitage’s newfound role as environmental ambassador.

Each poem, named after a species of moth, has its title boxed into the coffin of square brackets, and Armitage teasingly prompts us to imagine each three-line stanza as “two wings and a body part”. The whole collection is embalmed in the poet’s familiar wry humour. In [Small Waved Umber], the darkness of evening drops in like “a turd / through a letter box”, while [Brown-line Bright-eye] questions the appropriateness of Müller Fruit Corners as “graveside fodder”. In [Clouded Brindle], past “a candy-stripe helix / of incident tape, / chain and padlock”, a gravedigger is spotted, wearing a hazmat suit and those horribly squelching overshoes, with the absurd appearance of an earth-locked “astronaut”.

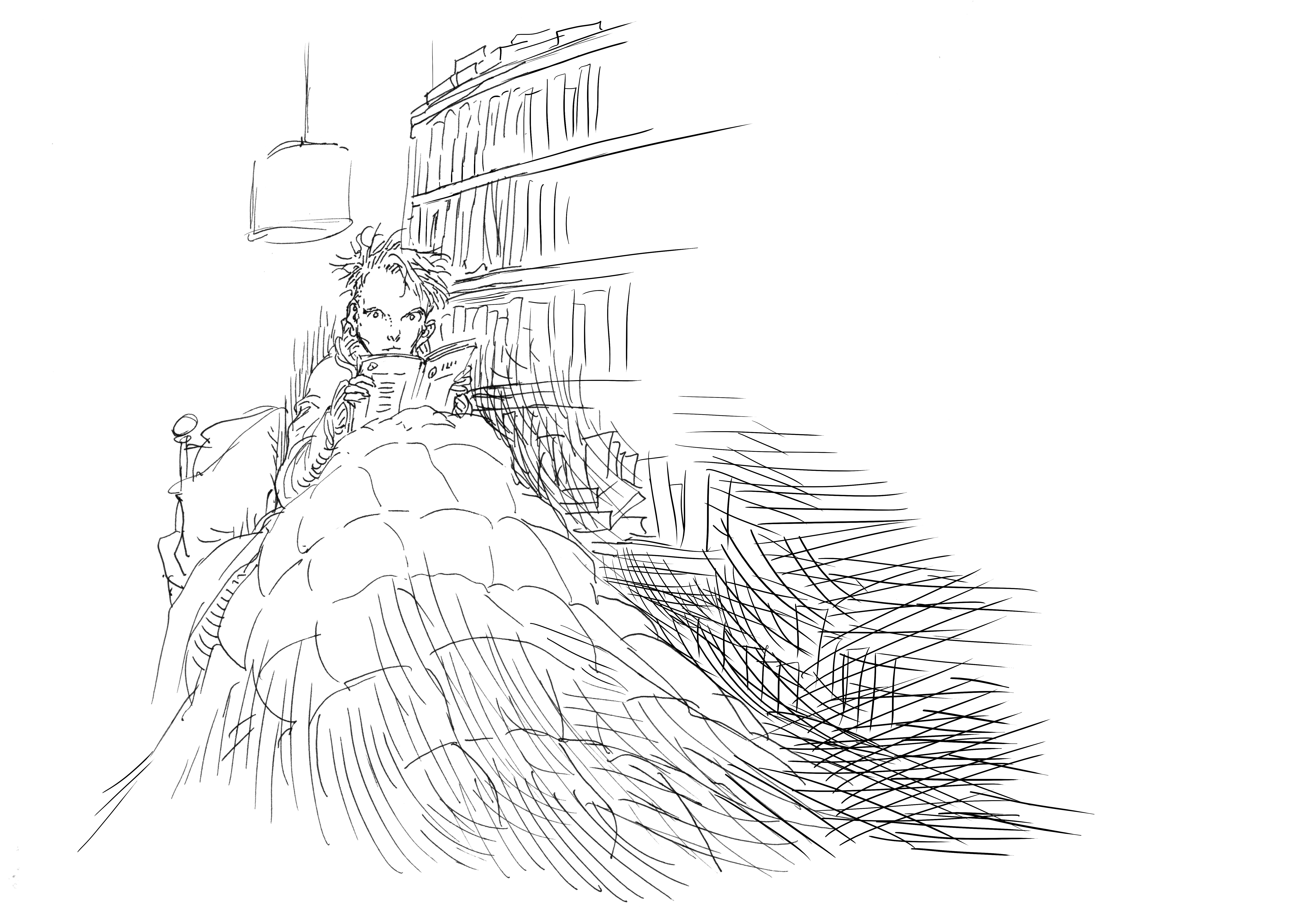

Reading New Cemetery is like playing hide-and-seek between tombstones. The “large-scale compositions and translations” of Armitage’s laureateship, he tells us, “came with more unforgiving deadlines”. Writing these tercets felt like “threading daisy chains or stringing shells” – and they are similarly fun to read.

I do not usually laugh at funerals – or cry over books. However, Armitage ploughs the soil of the dead – those “unable to love / but capable still / of being loved”, as the memorable final line goes – with such moving depth that I find myself doing both. This haunting volume demonstrates the magnetic pull of a mind that has kept us, across dozens of books published since 1989, mesmerised like moths to the flame.

[Scotch Annulet]

Related articles:

Dear reader,

this morning the poet

has gone to his shed

to tease

last night’s moths

from crannies and knots,

to tip the lampshade’s

treasure chest

onto an empty desk.

Because the wings of moths

are folded pages

of veiled script.

Because moths

bring word

from the dead.

New Cemetery by Simon Armitage is published by Faber & Faber (£14.99). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £13.49. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Paul Stuart

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy