“Once upon a time,” the story begins, lulling the reader into the seeming safety of the distant past. Is the intended reader a child? This book, a slender elegant hardback with large type and plenty of illustrations, certainly looks like a children’s book. But then, we were all children once – helpless, at the mercy of those who claim to care for us. No wonder Stephen King took on the task of writing a version of Hansel and Gretel to go with the late Maurice Sendak’s images, originally created for an opera, a form Sendak adored. For this is a horror story, and no mistake.

How is it that the stories of the Brothers Grimm have come to be considered suitable for young readers? This pair, born during the revolutionary end of the 18th century, collected their folk tales in a fervour of Teutonic nationalism. After the end of the second world war, their collections – the most popular books ever published in the German language – were initially banned, as it was felt they had contributed to the Nazification of Germany. The stories are full of trickery, witchcraft and murder: a great many of them embody not innocence but the death of it. Their resolutions often come at high cost.

Maurice Sendak (1928–2012) understood that darkness in his bones. He was born in Brooklyn to Jewish parents who had come to America from Poland in the years before the first world war; the shtetl was never far away. A sickly child, he suffered from measles, pneumonia, scarlet fever. Sendak told me at his Connecticut home in 2003 that his grandmother sewed him a white suit to wear, in the hope that if God spotted him in it, he would think “I was already dead because I was an angel.”

“This was something that went on in the ghetto. I had to be dressed so as to fool the fates – white, the colour, as if I was already gone.” White, too, is the colour of Max’s wolf suit in Sendak’s classic picture book, Where the Wild Things Are (1963). He is considered a “children’s author”, though he himself never made the distinction.

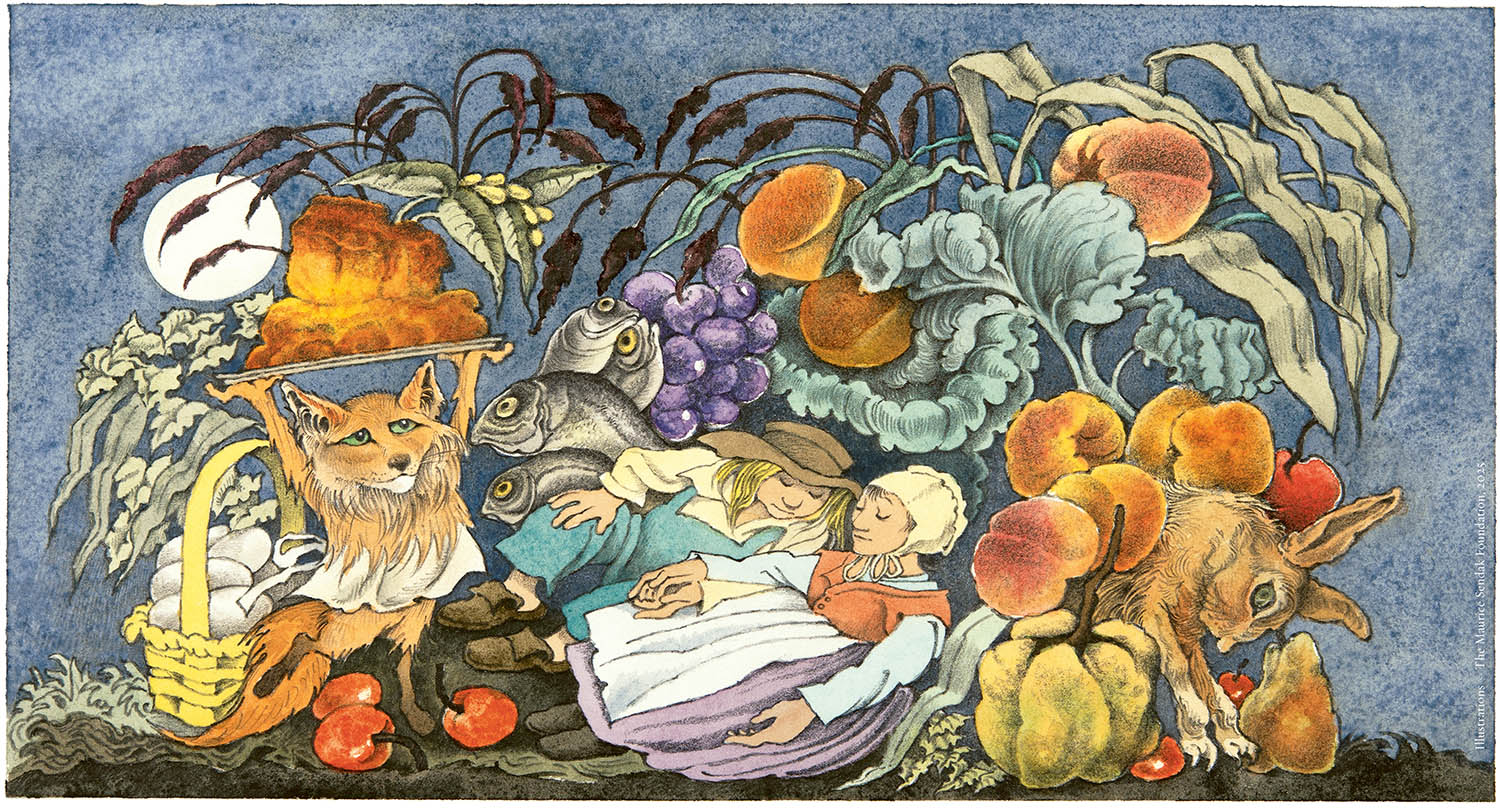

Death was always at the edge of his vision. As it is in his gorgeous, Blakean images for this tale, originally produced in the 1990s. (These were not the first illustrations he created inspired by the Grimms: a collection called The Juniper Tree, with translations of the stories by Lore Segal and Randall Jarrell, was published in 1975.) In Hansel and Gretel, if you peer into the soft watercolour of the roots of the forest trees the children are lured into, you will see them resolve into skulls. There are angels, dressed in white, spinning around the moon in Gretel’s dream – there’s Sendak’s grandmother again, of course – but on the opposite page is her brother Hansel’s dream, in which a wart-nosed witch flies through the air, captured children shrieking from the bag she carries behind her.

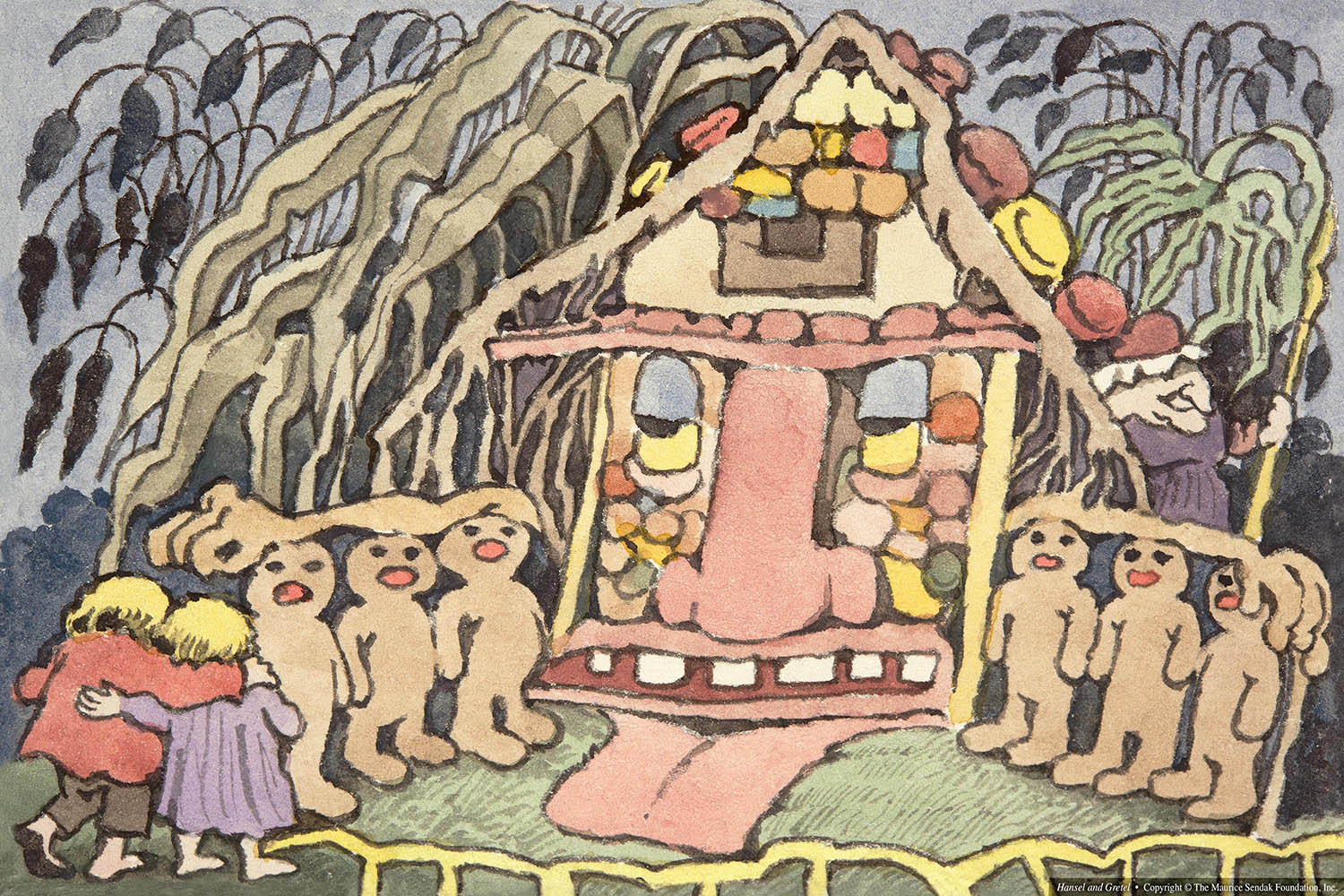

Most wonderfully – and this was the detail that pulled King into the project, as he writes in his introduction – the witch’s candy house is animate, its windows eyes, its door a great nose, a huge welcome mat of a tongue lolling out. When the children sleep, its evil is revealed, the walls dripping with slime, not sweetness: and the witch’s seemingly kindly face is restored to its evil truth.

King’s text is sturdy, though occasionally his use of the word “kids” and even “kiddos” jars against the more formal tone adopted elsewhere. He has, he admits, dispensed with some of the original elements of the Grimms’ version (“the magical duckling that takes the siblings across a lake or river struck me as a little too deus ex machina”, he writes; though in a story with edible homes and cannibalistic witches I’m not sure how he drew that particular line) but there’s no harm in that – Hansel and Gretel comes from a mutable, oral tradition. Fixed form, here, is an illusion.

So it’s worth recalling a horror that was, it seems, one step too far for King. Hansel and Gretel may have its origin in a famine that swept Europe in the wake of what is now called the little ice age, in the 14th century; parents would have been forced to make dreadful choices. In the Grimms’ original version, published in 1812, there was no stepmother in the tale: Hansel and Gretel were forced from their home by their biological parents. Later editions pulled back from the terror that is the mother who would kill her own children. Stepmothers have been traduced ever since.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

When Hansel and Gretel slay the witch by pushing her into the oven, they collect her treasure and bring it home to their (weak, but at least not actively murderous) father. They shower him with gold, diamonds, rubies, sapphires. “Now their cares were at an end, their father promised never to wrong them again, and you know what comes next.” Alongside the text here is a broad face, with hair that may or may not be the rays of the sun; the face is neither masculine nor feminine. Its eyes are cast down; it is not smiling; Sendak’s illustration is sepia, uncoloured. Famine stalks the world. And they lived happily ever after, indeed.

Hansel and Gretel by Stephen King & Maurice Sendak is published by Hodder Children’s Books (£20). Order a copy from The Observer Shop for £18. Delivery charges may apply

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Illustrations courtesy of the Maurice Sendak Foundation Inc