Memory haunts the work of John Burnside. The Scottish writer was a prolific novelist, a strange and beguiling memoirist, a critic, a chronicler of the natural world and a poet, producing more than 40 books before his death at the age of 69 in May 2024. I came to him first through his nonfiction, but the many friends of mine who are devotees of his work speak mostly of his poetry. As I spend more time with his words, I have come to see that what I love in his prose is caught and clarified in his poems, with painful precision. In his final collection, The Empire of Forgetting, a poem named The Persistence of Memory reads:

Barely a wave, then they’re gone, till no one is left,

and the dark from the woods closes in on myself alone,

the animals watching, the older gods

couched in the shadows.

Here, in a few lines, are the qualities that so move me in his prose: the confluence of solitude and communion; the pain and solace of a ravaged but persistent physical landscape. Burnside’s life was dedicated to its ruthless excavation and enshrinement.

I spent the summer of 2024 reading books about fathers. I cried at Philip Roth’s Patrimony when Herman Roth is overheard by his son, in his final years, while relieving himself in the toilet, crying out: “Mommy, Mommy, where are you, Mommy?” I was affected by the recounting of fastidious orderliness in Alan Bennett’s Untold Stories, his father wearing one of two suits every day of his life: one simply called “my suit” and the superior one called “my other suit”. I was embarrassed by the good-natured fatalism of Mordecai Richler’s dad in the face of familial ridicule: “Finally, there is a possibility I’d rather not ponder. Was he not sweet-natured at all, but a coward? Like me.”

Mostly, though, I was astonished by the preponderance of fathers as liars; fathers outed as fabulists and fantasists; fathers as architects of flimsy unrealities which come apart either slowly through a life or all at once in the undoing of death. Though their lies are rooted in failure, shame and inadequacy, there is also the feeling of it being somehow inevitable or appropriate that the father is so entitled to create the world around him, the father being the closest thing to God that the family has – why oughtn’t he define the universe? It’s his own. Geoffrey Wolff writes of such a father in The Duke of Deception, and so does Mary Gordon in The Shadow Man, but nobody has ever written of the lying father as startlingly as John Burnside.

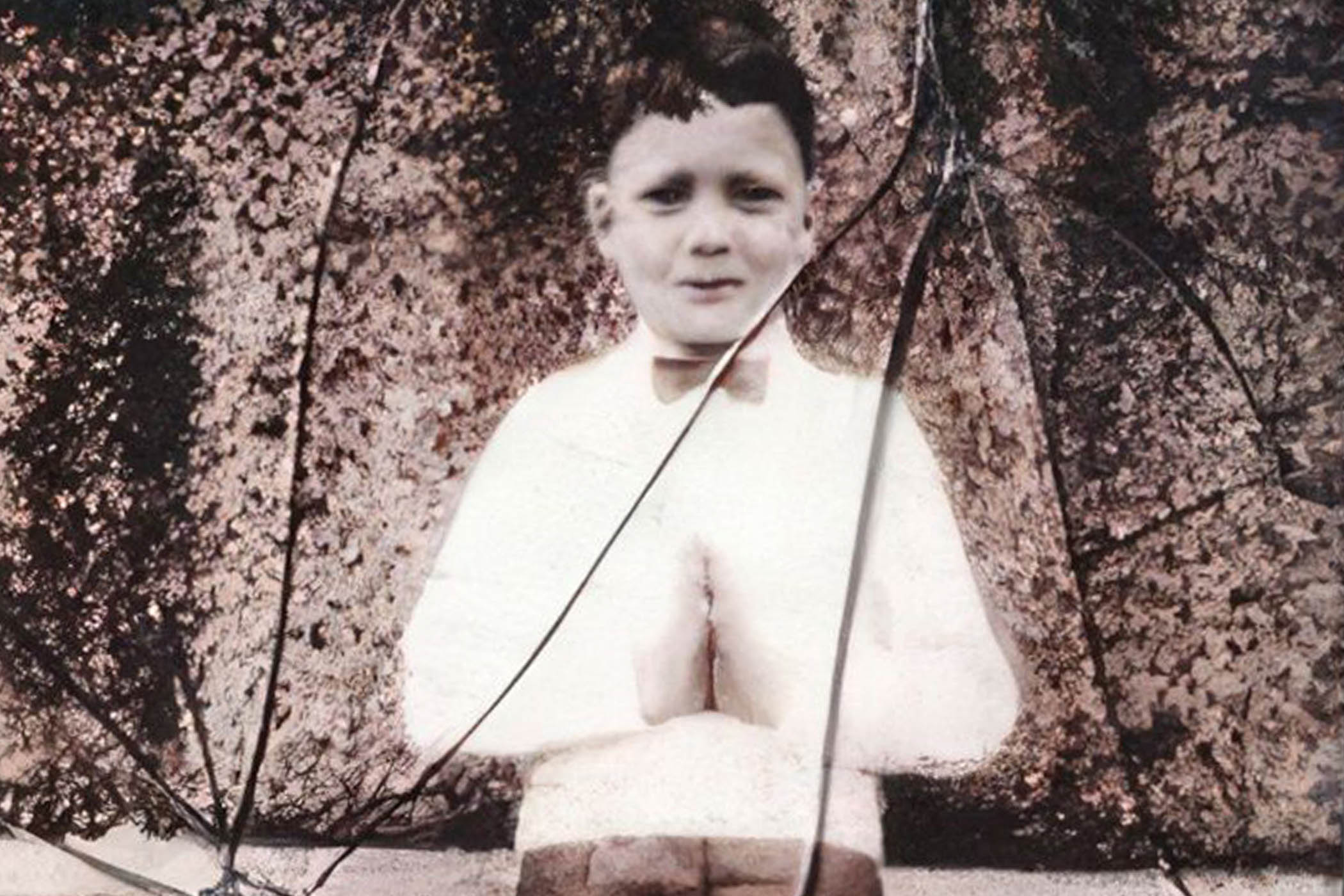

Burnside’s A Lie About My Father was published in 2006, at the time when the market was saturated with “misery memoirs” of childhoods marred by violence and abuse. Though Burnside’s work could hardly be more distinct from that genre stylistically, his father Tommy in some ways could have been cast quite neatly in a conventional narrative of this kind: the hard-drinking, churlish, taciturn patriarch with a savage streak, quick to anger and to demolish innocence (early in the book, he finds Burnside’s beloved teddy, Sooty, “strewn across the floor” and throws it on the fire as a punishment, telling his six-year-old son he was too grown up for such things in any case). It’s the absence of such familiarity that makes this book so singular and haunting. The equanimity with which Burnside regards both his father and himself is not unlike the calm insight that pervaded his nature column in the New Statesman, a meeting of emotion and intelligence so congruous and complementary it seems a genre all its own. The preface to A Lie About My Father reads:

This book is best treated as a work of fiction. If he were here to discuss it, my father would agree, I’m sure, that it’s as true to say I never had a father as it is to say that he never had a son.

All recollections of family dynamics would benefit from the acknowledgment of inherent subjectivity, the impossibility of accuracy, but particularly in a story of inherited invention – Burnside doomed, at least in the ignorance of childhood, to unknowingly repeat the lies told by Tommy.

Some of the recurring lies are frivolous bits of nonsense, meaningful only in their persistence and repetition, such as the claim that he had been told he resembled Robert Mitchum, or had begun a promising career in football before joining the army, cut short by injury. The foundational myth of his life, though, was revealed years after his death, and then only by accident.

The story during his lifetime had been that he was adopted by an uncle after his biological father, an industrialist, had got a factory girl pregnant. The details varied but the premise was the same: he had parents, their identities were known, and they had given him up to other respectable foster parents. In fact, Burnside is corrected by an aunt, years after the death of his father: Tommy Burnside was left abandoned on a doorstep and shuffled about in a haphazard manner for the remainder of childhood, never adopted. A foundling, she called him, a word fittingly from the realm of mythology and fairytale.

Too clever and generous a thinker to allow this to explain his father in its entirety, Burnside does nonetheless acknowledge that temptation. Of course his father had to become a consummate liar, a maker of stories, because the true story was simply not acceptable. Any story – all stories – were better than the total lack of one, just as any parents, adoptive or not, were better than the void he had actually emerged from.

Burnside writes about members of that generation and how the omission of defined origins would wound them:

It mattered, once upon a time, where a person came from, and my father didn’t feel he had the luxury of saying, as I can, that it doesn’t matter where a man was born, or who his ancestors were. Nobility, honesty, guile, imagination, integrity, the ability to appreciate, ease of self-expression – in his time, most people believed that these were handed down by blood.

Burnside’s father had no known blood, no natural way to assert himself in the world, and asserted himself instead with the tools available to him – not just fantasy but aggression and belittlement. And, crucially, when it came to his relationship with his wife, Theresa, an oppressive insistence on defining the temperament of the home.

Some of the most painful parts of this book involve this overbearing determination of the domestic space – when Tommy is back from the pub, pissed, with a friend or two in tow, warding off his wife with her dour, feminine, sensible energy. Burnside, a precocious pre-adolescent, is roused from his bed to attend to the drunk men, pouring their drinks and prompted to recite facts. He learns to balance this performance, to be bright and charming enough to please but not so much that he looks to be showing off. The threat implied in these evenings is not necessarily realised, often descending instead to depressing chaos (as when Tommy brings home two hedgehogs in a sack and is morose and bitter not to be praised for it), but as his drinking and gambling become more unpredictable, the atmosphere shifts into one of more concrete menace.

Tommy’s increasing restlessness builds to scattershot attempts at starting over, transforming the family fortunes. These plots are seen accurately as unrealistic and fanciful by Theresa, who is nonetheless compelled through her exasperated dutifulness to allow the schemes to play out in the fullness of their failure.

The foundational myth of Tommy Burnside's life was revealed years after his death, and then only by accident

The foundational myth of Tommy Burnside's life was revealed years after his death, and then only by accident

The family moves from Cowdenbeath in Scotland to Corby, near Birmingham, where Tommy’s growing alcoholism and aimlessness prevent any improvement in finances or other affairs. Burnside describes the blunt efficacy of the particular manner of drinking that he will go on to inherit from his father. It is one without pleasure or comfort, ritualistic and punitive. The mornings after would be equally unpleasant: “The hangovers were pure murder, but he still got up and went to work. He’d never missed a day’s work in his life through drink, he would say, and he never would.” Then there is a plan to move to Canada, conjuring for his son a romantic vision of a place so alien and beautiful and remote it might act as a real redemption for all the oddness and injury of his family. When that plan, too, evaporates, Burnside begins to understand the true scale of his father’s weakness and unreliability. Tommy’s disdain for Burnside’s finer – “and so, weaker” – self coagulates as father and son’s lives diverge.

By the beginning of his young adult life, Burnside’s artistic pursuits and navigation of the natural world – wonderfully connoted by the phrase “the dense, communal silence of beasts” – have been joined by a reverent appreciation for LSD, which he describes as sacramental. The drug-taking marked a significant divergence in the father-son relationship, one that would only increase following Theresa’s death. Drugs, especially LSD, were not just alienating and indicative of unwarranted notions, like art – they were disturbing in a more profound and suggestive personal sense. Once they have had their confrontation about it, a division occurs:

That last remark, however, said it all: it’s up to you. It was what he said whenever he gave up and washed his hands of a problem. That night, he was washing his hands of me and, as the door closed behind him, I hated him for it.

To experiment, to be open to novel experience, goes against everything fundamental in Tommy’s understanding of what it is to be a working-class man: the ability to take pain, control surroundings, and avoid shame.

Memoirs about fathers are often seen as an act of patricide, a child getting in the final word with no small amount of spite or necessary vanquishing. Here, something more melancholy takes place: not the shattering of oppressive strength but a slow and patient excavation of a weakness that was always there. For a man like Tommy, and particularly one without an origin story, such an exposition is intolerable to imagine. This is clearest in his horror of a public death – the disgrace of the ultimate weakness, illness and expiration, taking place in front of strangers.

“Whatever else happens, don’t let me go like that,” Tommy pleads of his son following his third heart attack, though he would go, finally, in a pub in Corby among a crowd of his fellow drinkers and friends, on his way to the cigarette machine. In begging not to be allowed to die that way, Tommy reminds John of a scared 12-year-old, a minor fragment of the “beautiful and inexplicably tragic figure he had sometimes cut in my child’s world, sitting at family funerals and weddings with the other men, a dark, bruised presence, shrouded in whisky and smoke.” The beauty, finally, of A Lie About My Father is its symphonic ability to see to all those childhood lineaments still present in both father and son, the acts of cruelty and the occasional, dazzling pleasure, the boys alive in both men unable to witness each other in life.

A Lie About My Father (Vintage, £10.99) and The Empire of Forgetting (Jonathan Cape, £13) by John Burnside are available with a 10% discount from The Observer Shop. Delivery charges may apply.

Editor’s note: our recommendations are chosen independently by our journalists. The Observer may earn a small commission if a reader clicks a link and purchases a recommended product. This revenue helps support Observer journalism

Photography by Getty Images; courtesy of author

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy