“Does it matter that Yeats ‘detested parsnips’?” To most readers of the Irish poet the answer will likely be a resounding no, but it mattered to the scholar and biographer Richard Ellmann, who harvested every possible anecdote and snippet of information from Yeats’s friends and acquaintances while he was researching his first book, The Man and the Masks.

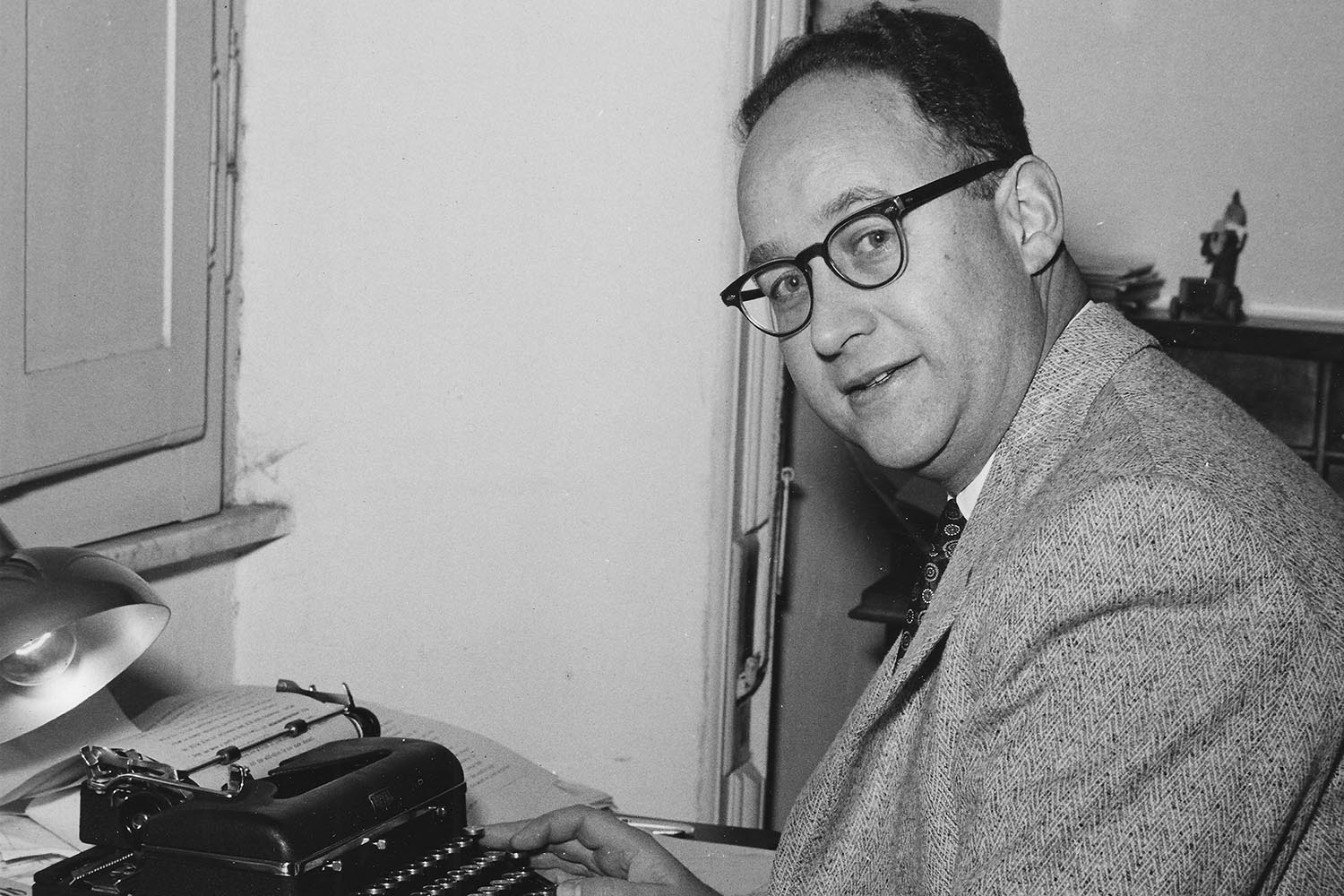

This was an invaluable apprenticeship for Ellmann’s writing of his magnum opus, the 1959 biography of James Joyce. This book set a new and enduring standard for how the life of a modern writer might be written. Ellmann – a Jewish-American academic who taught for most of his career at Northwestern University, near Chicago, and then at Oxford – tracked down Joyce’s relatives, friends, acquaintances and enemies, getting access to their personal memories and to private letters stashed in their closets. But he combined the sleuthing and smooth-talking with the knowledge and sensibility needed to make sense of Joyce’s dense, fiercely erudite, often rude and ribald works, whose capaciousness found room for most of European culture alongside the sights and smells of 20th-century Dublin.

The way in which Ellmann’s remarkable biography came into being is the subject of an unusual and eminently humane new book by Zachary Leader, himself a distinguished practitioner of the erudite yet highly readable doorstopper school of biography that Ellmann pioneered, via his lives of Kingsley Amis and Saul Bellow.

Leader explains from the outset that this will not be one of those biographies that agonises about its subject: “He was a good man,” he states of Ellmann on the second page, and this warmth of feeling is a winning quality. He takes us through Ellmann’s childhood experiences in Michigan, early travels in Europe, wartime activities in the US navy, marriage to the non-Jewish Mary Donoghue, which threatened to alienate him from his parents, and the stages through which he climbed the ladder of academic prestige towards his book on Joyce. Leader is never fawning, nor does he downplay the aspects of Ellmann’s personality – occasional craftiness, self-promotion and competitiveness – which, while less appealing, were no less essential to his success as a biographer, especially of a writer whose legacy was contested by as many jostling and self-interested parties as Joyce’s was.

Many details are delightful, like Ellmann grabbing a dance with Marlene Dietrich in Paris

Many details are delightful, like Ellmann grabbing a dance with Marlene Dietrich in Paris

Leader’s depiction of Ellmann is deliberately Ellmannesque. The great power of the latter’s Joyce biography was the way that it made sense of Joyce’s difficulty, both as a writer and a person. Whereas earlier critics had read Joyce’s depiction of Leopold Bloom, the hapless hero of Ulysses, as cruelly satirical, Ellmann insisted that Bloom should be read as a warmly rounded depiction of ordinary fallibility and limitation, and he extended the same courtesy to Joyce himself, whose self-absorbed hyper-intellectualism is not always easy to like. As Ellmann reads Joyce and as he reads Bloom, so Leader reads Ellmann, even giving a coolly non-judgmental account of the extramarital affair into which he entered at the end of his life, after Mary (who comes across as a sharp and dogged figure in her own right) had been incapacitated by an aneurysm.

At one point, Leader quotes a scholar friend praising Ellmann for “the eagerness of your beaverosity”, and Leader’s own beavorisity is voracious but, at times, excessively so. Many details are either riveting as insights into the biographer’s art or simply delightful, like Ellmann grabbing a dance with Marlene Dietrich in Paris at the end of the war. Others take us back to Yeats’s parsnips: do we need to know about the time in September 1951 when Ellmann spent a day cleaning his new house in Evanston, Illinois, with the help of two hired college students? I’m not asking this question rhetorically, because I think Leader poses it quite deliberately. Just as Ulysses had elevated the granular textures of a day in Leopold Bloom’s Dublin life to the status of epic, so Ellmann wrote to a colleague: “I am endeavouring to treat Joyce’s life with some of the same fullness that he treats Bloom’s life.”

The fiercely erudite James Joyce

If this makes some passages in the book’s first half taste a little too much of parsnip, the account of the Joyce biography itself provides the full Sunday roast, offering a lucid account of what makes Ellmann such a consummate practitioner of an art of writing that, Leader clearly feels, does not always receive the respect that it deserves. The most compelling sections of the book explore the tension at the heart of Ellmann’s approach to Joyce, which saw him conferring coherence not just on Joyce’s erratic life – he fell out with almost everyone he ever met – but on his great and challenging novels, Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, that often seemed to lay waste to human sense-making. This talent for finding coherence in the borderline incoherent led to his book being larded with praise and prizes – and a degree of suspicion from a later generation of Joyce scholars who saw Ellmann as having made the life and the work a little too neat and transparent.

For all the book’s richness, there is something un-Joycean about Ellmann’s creation of what one critic calls “completion and tidiness” in his biographical narrative. Leader defends this decision: “Stories, after all, are how most people, including most academics, know and present not only the lives of others but their own lives.” This is surely true, but, as Leader acknowledges, it also reflects Ellmann’s preference (which he seems to share) for the fragmented but coherent narrative of Ulysses over Joyce’s more wild and baffling experiments with language in Finnegans Wake. Leader’s compelling defence of the biographer’s art implicitly poses a strange, perhaps unanswerable question: could there be a thoroughly Joycean biography of Joyce?

Ellmann’s Joyce: The Biography of a Masterpiece and Its Maker by Zachary Leader is published by Harvard University Press (£29.95). Order your copy from observershop.co.uk. Delivery charges may apply.

Photographs by Lucy Ellmann; Getty

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy