In the early 20th century, the race to stake a claim to the future of art was as furious as the scramble for Africa a generation earlier. Its colonising pioneers came from all over Europe, guided by feverish dreams of glory. Picasso carved out a path to cubism and helped himself to indigenous cultures. A group of Italians, roped together by quasi-fascist ideology, penetrated deep into futurism. And from Britain came the vorticists, men and women who were fascinated by the elusive moment when everything stands still at the centre of a great centrifugal force, like the fleeting instant snatched by the then modish technology of photography.

All of these movements were a response to the dawn of the machine age and the rumble of the looming first world war. For the vorticists, who included Wyndham Lewis, David Bomberg and sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, this meant a collision between representation and abstraction. In their art, human figures appeared to be surrounded by a thicket of pick-up sticks: concertinaed structures that represented engines and weapons.

That said, the vorticists didn’t need the storm of a global conflict to find their voice. James King’s group biography suggests that they were perfectly capable of gaining global attention by themselves. His account includes tyro artists hitting their tutors with their palettes, and the tutors not unreasonably despising the artists in return. Vorticists let off fireworks in art galleries, and jealously denied their peers opportunities at exhibitions by hiding their paintings. Their sex lives were prodigious. A sometime spokesman for this school made one of the more unlikely complaints ever levelled against London Underground when he claimed that a steel staircase at Piccadilly Circus was the most uncomfortable place he’d ever had sex.

The vorticists frightened the horses – literally. When Bomberg’s angular The Mud Bath was hung outside a gallery as a publicity stunt, the drays pulling the Number 29 bus were “startled by the painting and shied away from it”, reported the Daily Chronicle.

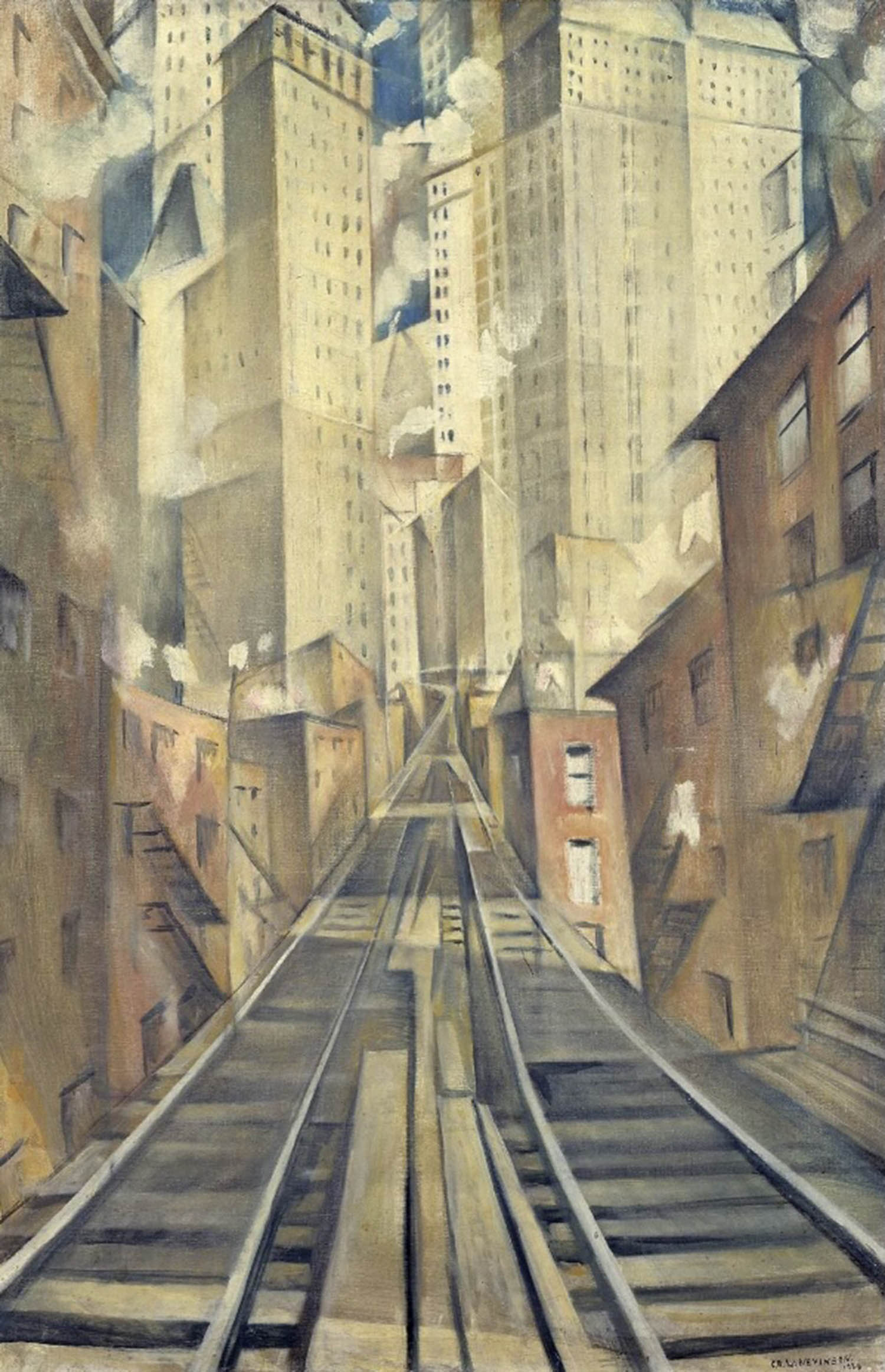

CRW Nevinson’s 1920 painting The Soul of the Soulless City (detail), AKA New York: An Abstraction

The leading provocateurs of the movement were Bomberg, T E Hulme (of that steel staircase line) and, above all, Lewis, the vain and insecure concealer of others’ pictures. The novelist Ford Madox Ford once encountered him in a “cape of the type that villains in melodramas throw over their shoulders when they say, ‘Ha-ha!’” There would have been no vorticism without Lewis.

King profiles the core members of Lewis’s group, including two women, Helen Saunders and Jessica Dismorr, who have often been overlooked by the art world, including their fellow vorticists. Emerging around 1912, they rubbed tweedy shoulders with contemporaries such as the painter Vanessa Bell and Roger Fry, artist and influencer avant la lettre. The heart sinks at the prospect of yet another book featuring the Bloomsbury set – but the gelignite-like instability of Lewis soon meant that the artist fell out with Fry, his would-be patron. “The conflict became Miltonian. Lewis became a proud Lucifer who rebelled against a remote God,” says King in his revealing and very readable study.

Critics claim that artists of this period were so mesmerised by machinery that they were unprepared for the horrors of the Somme in the first mechanised war. The Italian Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, leader of the futurists, impatiently anticipated the bloodshed, declaring: “We wish to glorify war – the only health-giver of the world.” But the vorticists were always against the conflict.

Time has been kind to their greatest hits. CRW Nevinson, who was associated with the group, painted one of the most resonant motifs of the emerging urban environment in New York: An Abstraction. Lewis lived up to his exalted estimation of himself with works such as The Crowd, in which figures can be glimpsed inside what might be a giant circuit board, an eerie prefiguring of our lives lived on the grid – or, rather, in it. These haven’t dated; on the contrary, they’re prescient. The vorticists’ images of people trapped by collapsing scenery could almost be storyboards for director Christopher Nol an’s experiments with time and space a hundred years later.

Perhaps the greatest artist to emerge from the group was Bomberg, who went on to paint striking Spanish landscapes in a figurative, expressive style, and to teach the young Frank Auerbach. The gang might not have been naive about the great war, but it was the end of them, all the same. Hulme and Gaudier-Brzeska were killed at the front. Conflict meant chaos, so vorticism – attempting to find the hiatus at the middle of pandemonium – went against the zeitgeist, says King. English art proved resistant to abstraction and even some of the vorticists themselves turned away from it. By 1915, the movement was all over. It was a storm in a teacup. But if you listen closely, you can still catch an echo of the flying crockery.

Order Our Little Gang from observershop.co.uk to receive a 10% discount. Delivery charges may apply

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy