In the autumn of 1918, as Spanish influenza swept the British Isles, a popular children’s rhyme caught the ease with which the flu was transmitted: “I had a little bird / Its name was Enza / I opened a window / And in-flu-enza.”

The rhyme reflected the widespread belief that the flu was an airborne pathogen that could be carried over long distances. Some medical experts agreed, arguing in the Lancet medical journal that windows in hospitals should be kept shut to prevent the bug entering convalescent wards. But British health officials, drawing on medical advice, disagreed. Instead, they urged people to use a handkerchief to “intercept drops of mucus” and to avoid coughing and sneezing when in public.

Fast forward 100 years to Covid-19 and the advice was almost identical. Despite numerous studies in between showing that pathogens such as tuberculosis and measles, which are much larger organisms than either influenza or coronaviruses, could linger in the air for hours at a time, on 28 March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) issued a tweet insisting, in capital letters, that “#COVID19 is NOT airborne” and that “the #coronavirus is mainly transmitted through droplets generated when an infected person coughs, sneezes or speaks”. Instead, people were advised to keep one metre apart and to wash their hands and disinfect surfaces.

How this “droplet dogma” came to be adopted by the WHO and other authorities around the world is the subject of Carl Zimmer’s fascinating new book. An acclaimed science writer, Zimmer has written widely on viruses and parasites, and during the Covid pandemic contributed to coverage that won the New York Times the public service Pulitzer prize in 2021, so you would think he would have been on to this canard from the start. But no. Like everyone else, this author included, Zimmer accepted the official advice, reasoning that, if he kept one metre from strangers, he’d be safe and any virus-laden droplets that came his way via sneezes or coughs would, as he puts it, “fall to the floor like ball bearings”.

What changed his mind were superspreader events, such as the infection of 53 members of the Skagit Valley Chorale in Mount Vernon, Washington, by a single infected singer who, Zimmer writes, “released an invisible cloud of droplets so tiny that they resisted gravity and floated like smoke”. Two of the choristers died.

The choir provides a useful entry point for Zimmer’s wide-ranging study of the forgotten science of aerobiology. The study of the movement of microorganisms in the atmosphere from one geographical location to another, aerobiology is not to be confused with miasma theory – a much older idea, dating back to Hippocrates, which posits that diseases are because of poisonous emanations from putrefying organic matter and/or environmental “influences”.

For centuries, miasma theory had dominated medical thinking, but with the rise of bacteriology in the 1880s and the identification by Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur of specific microbes for specific diseases, it was gradually displaced by germ theory.

Diseases such as tuberculosis and cholera, microbiologists showed, were because of bacteria transmitted by water or over short distances by contaminated breath. Followers of the new sanitary science emphasised the importance of clean water and food, and the rapid isolation of the sick. In the process, they side-stepped the question of how far bacteria and other particles, such as disease-carrying spores and fungi, could be conveyed via air currents.

Related articles:

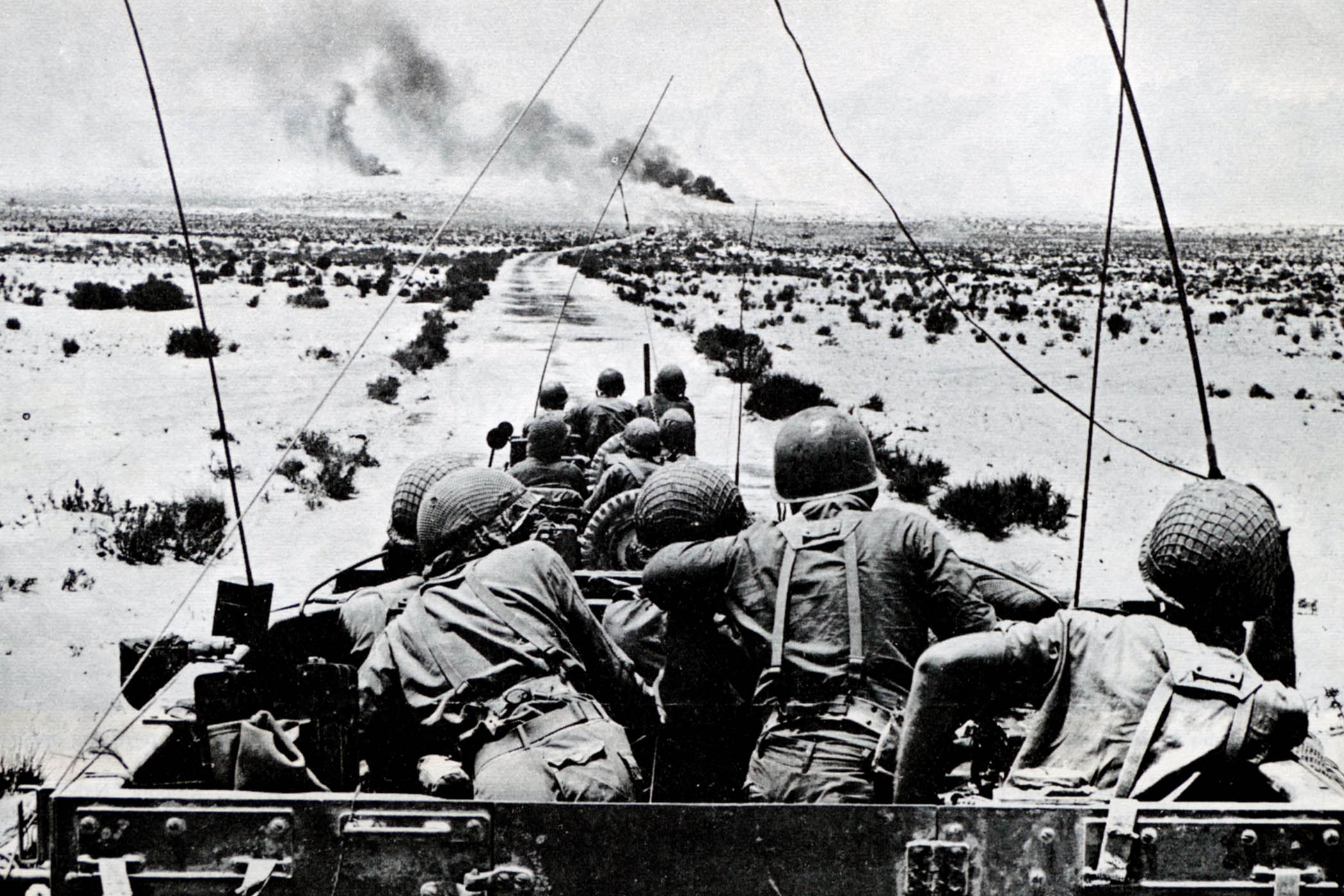

In Air-Borne, Zimmer takes us on a wide-ranging tour of the history of aerobiology, from the early investigations of plant pathologists into diseases such as rust and potato blight, caused by tiny wind-driven spores, to pollen and bacteria floating high in the atmosphere. In the process, we learn of the surprising role of aviators such as Amelia Earhart and Charles Lindbergh in these investigations and of second world war biowarfare experiments involving airborne pathogens such as psittacosis.

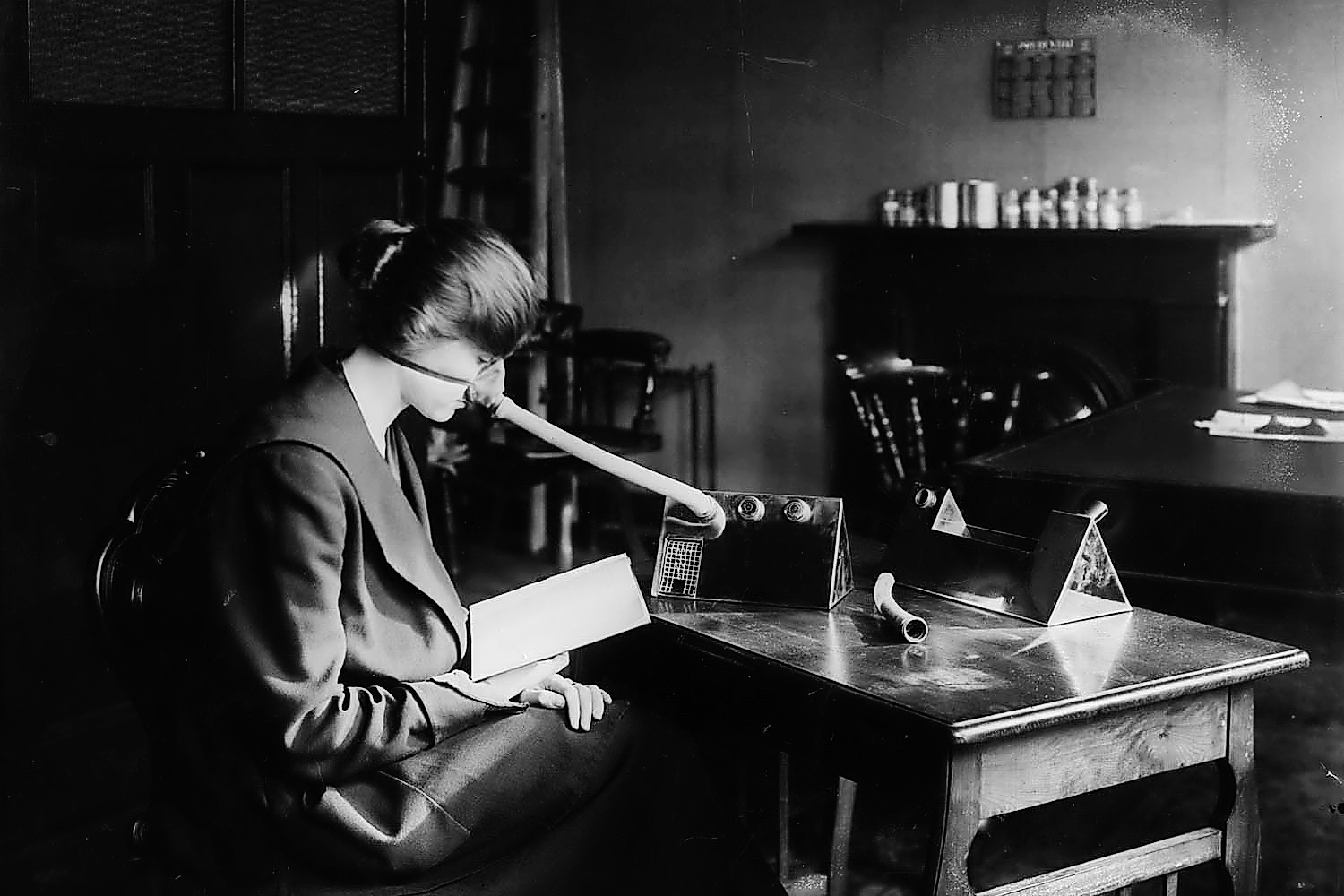

However, Zimmer’s principal focus is an American sanitary engineer, William Firth Wells, who in the late 1930s invented an “infection machine” – a large bell jar housing a cage of mice into which bacteria-infested air could be sprayed via a long glass tube. Having demonstrated that the bacteria-laced droplets infected the mice, Wells installed ultraviolet lights in a school in Philadelphia during a measles epidemic. He and his wife Mildred were able to show that rates of cross-infections with measles were significantly lower in classrooms where UV lights had disinfected the air. This could not have occurred if transmission was just because of droplets that fell to the ground.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Much of Air-Borne – too much for my taste – is taken up with detailed descriptions of Wells’s experiments and his struggle to win wider scientific acceptance. In Zimmer’s telling, Wells was a poor communicator who was forever falling out with colleagues. The result was that when, during the 1957 influenza pandemic, researchers inspired by his work showed that UV lights had protected patients from flu, a prominent British flu expert casually dismissed their findings. And so it continued, through the Sars outbreak in 2002 and the 2009 swine flu pandemic. In each case, respiratory disease experts ignored the growing evidence of airborne spread, insisting that the main mode of transmission was via close-range droplets or fomites – infectious particles that attach to surfaces such as doorknobs. The result was that it wasn’t until the close of 2021, and the experience of the more infectious Omicron variant, that the WHO finally adjusted its advice and acknowledged that “long-range airborne transmission” could occur in poorly ventilated or crowded indoor settings.

Zimmer should be applauded for recovering the hidden history of aerobiology. However, he fails to spell out how the mantra “follow the science” undermined faith in public health authorities and trust in science, resulting in non-compliance with social distancing regulations and fuelling political polarisation. That, in my view, is a missed opportunity.

Air-Borne: The Hidden History of the Life We Breathe by Carl Zimmer is published by Picador (£25). Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for a special 20% launch offer (ends 11 June). Delivery charges may apply

Photograph by Getty