What is dance? And, more specifically, when is a show dance and when is it theatre? The lines in recent times have become increasingly blurred. The Venice Dance Biennale’s 2025 Silver Lion went to Carolina Bianchi, who is definitely a theatre artist, but whose body is central to her storytelling. And at a festival such as Edinburgh, particularly on the fringe, the question seems ever more pressing.

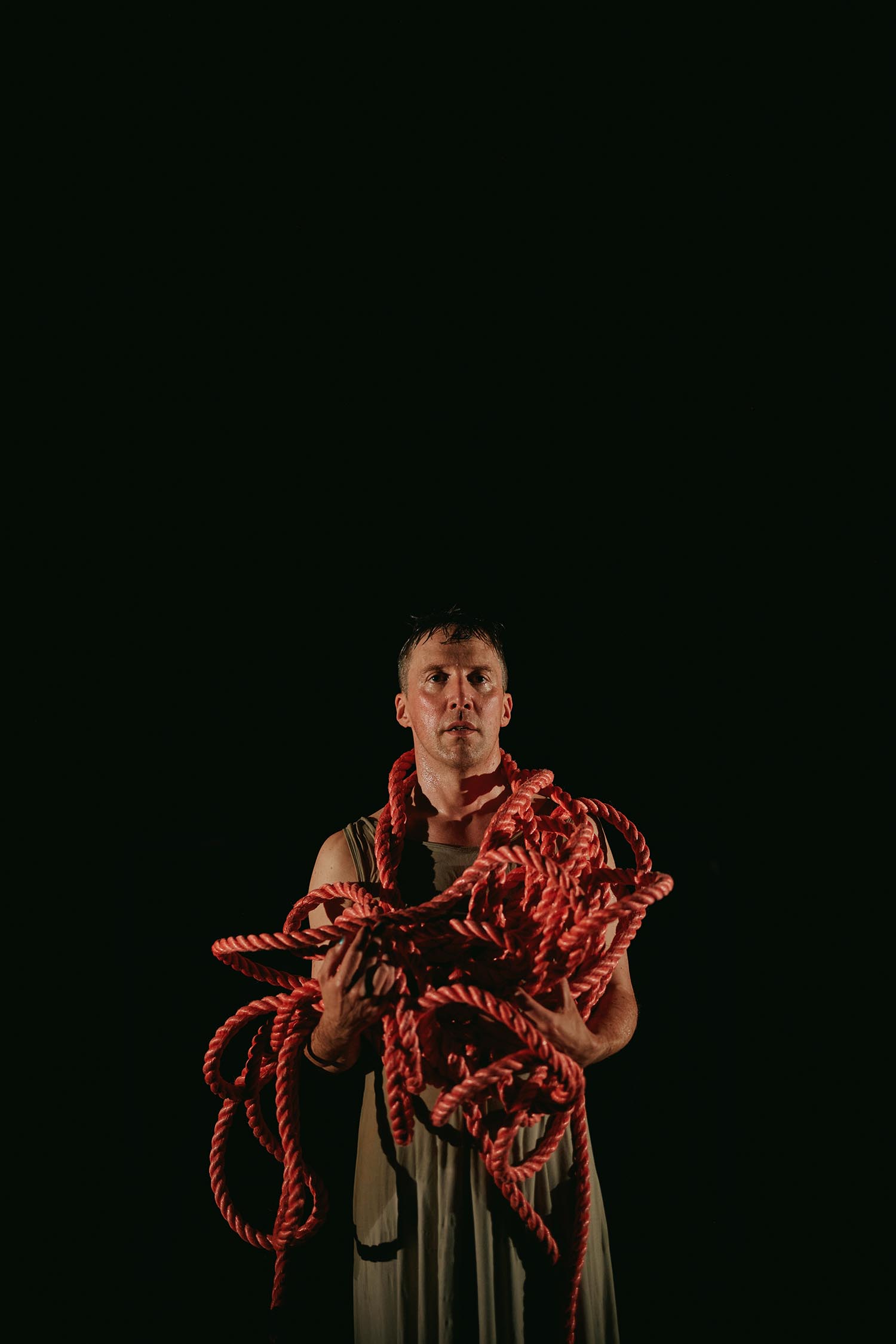

The enterprising, Glasgow-based Company of Wolves presented a gripping version of The Bacchae (Assembly Roxy) as a one-man (Ewan Downie) theatre show. Yet movement – long passages of dance represent Dionysus “god of dancing, god of change” – is the key to its storytelling. Belgian theatre collective FC Bergman showed Works and Days (Lyceum) in the international festival’s theatre strand; here, not a word was spoken. The narrative – following a community living in harmony with the land and then becoming separated from it – unfolded entirely through action, gesture, music and movement.

In many ways it doesn’t matter how you define these things. If they work as communicative art, then labels should be irrelevant. But I sometimes sense that dance-makers feel a certain pressure to communicate with language as well as with their bodies, as if lacking confidence in their physical ability to make their message understood.

In Akropolis I, a solo presented at Dance Base by Kennedy Junior Muntanga, the dancer actually mutters “Just dance!” under his breath, but seems reluctant to follow his own advice. It’s a shame, because he is a devastatingly good dancer, full of presence and ideas, his choreography unleashing a coiled energy that sets him off in sweeping curves and crouches.

Standing facing the audience, he contorts his face and shouts “fee, fie, fo, fum”. Struggling to move, he says: “You have to push yourself” and “It’s about my family”. I didn’t know what it was about, but the dancing is full of an engrossing clarity that the dramaturgy lacks.

Ewan Downie in ‘gripping’ one-man show The Bacchae

Sometimes words muddy the waters in other ways. The first 15 minutes of Wendy Houstoun’s Watch It! at Zoo Southside are a model of sophisticated concentration, as this veteran of Lloyd Newson’s physical theatre company DV8 traces the passage from the 1960s to the present day. Simply by virtue of altering the way she marches on the spot, changing the inflection of her feet from fierce feminist protest to chic corporate woman, arms plucking ideas and words out of the air, she paints a vivid picture of the times. Her gestures perfectly conjure images for the quickfire language, spat out like a word association game into a standup microphone. While always witty and challenging, the show gets bogged down in its own arguments about freedom of speech and wokeness, but that opening passage was memorable.

I also fell for the good-hearted directness of Glasgow’s Barrowland Ballet, who presented two shows on sharply contrasting themes. Wee Man at Dance Base, directed and choreographed by artistic director Natasha Gilmore to music by Luke Sutherland, was an exploration of the challenges faced by young men as they try to define their masculinity. Set in a football club where older men initiate young hopefuls into the rules of the game and of life, the script by Kevin P Gilday was transmitted over loudspeakers and via projections inside the goalposts on either side of the stage.

It was full of sharp observations about the shapes men force themselves into – “Never show emotion – or eat salad”; “Dance like Gene Kelly, not Fred Astaire” – and some expressive, multigenerational dance, full of breaking moves as well as balletic leaps. But it felt slightly overextended, as if too anxious to make its very good points.

Chunky Jewellery, Wee Man’s female-leaning counterpart, performed at the Assembly Rooms, was much more confident and better shaped. Created and performed by Gilmore and her real-life friend Jude Williams, with Ben Duke of Lost Dog as co-creator and director, it begins with a discussion of how you make a fringe show and what ingredients it might need. “It’s the terror that’s motivating,” Williams says.

As the show progresses, it becomes the story of a friendship that supports the women through loss and trauma as they make their way in the world with children in tow and men nowhere to be seen. The script is rich, switching between humour and a poetic but felt emotion. The dance is minimal but hugely expressive as Gilmore sketches steps around the space, movement, beginning in her shoulders and spreading to her whole body as she searches for happy memories, or turns on the spot, one arm swinging fiercely across her body as she remembers sad ones.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Her movement is matched by Williams’s rich voice, singing songs of sadness and hope. It’s a wonderfully realised piece of theatre. Is it ballet? Certainly not. Is it dance? Who cares. It’s just very truthful.

Photograph by Brian Hartley/Louise Mather