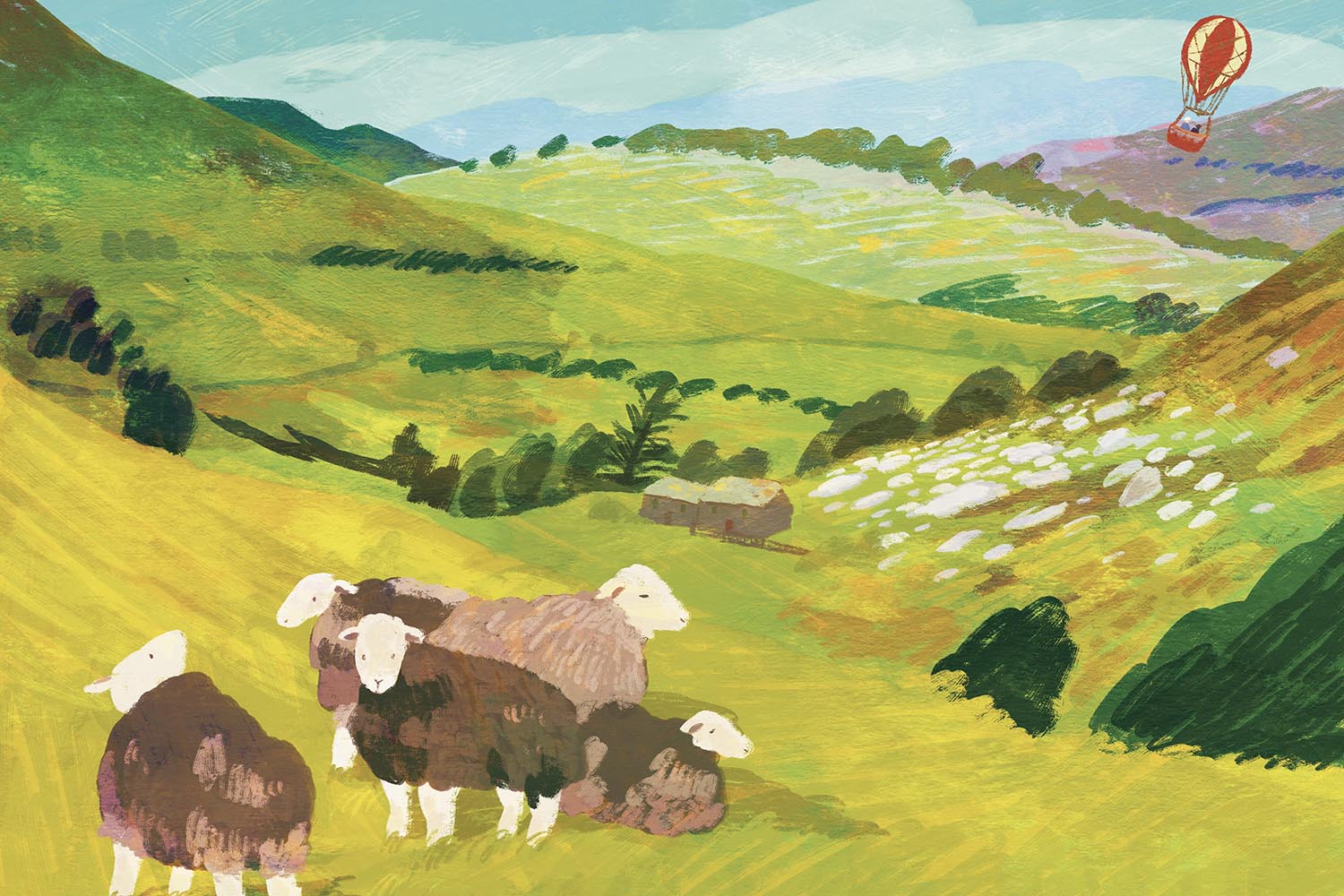

Illustrations by Natsumi Chikayasu

O! But what manner of airborne creature is this? This great, gaseous, patch-skinned thing hanging up above the valley? A bright red os on the horizon; a lost, seethrough sun, or mackintosh planet, growing larger, coming closer on the light prevailing breeze, excusing itself through the low clouds as if it has important business up here, in Helm’s realm. What unearthly bladder or florid hollow could it be, drifting towards the fell, where Helm sits (or stands, or squats, or savasanas) boggling at it. A contraption never seen before, incomprehensible, undoing the laws of physics, though Helm is becoming accustomed to the way weird things keep occurring; humans being obsessed with new inventions, manically productive in their cottages, mills and workrooms.

Never before something of this ilk! A fat diaphragm of papers and silks, declarative in its primary hue, full of hot fiery ego, its globular materials stitched and stuck together – jellyish, viscous, really quite hideous. With, slung from its preposterous body, a little woven basket containing not the experimental, expendable barnyard guinea pigs à la le continent, but a man inside it. A man, and a woman, sporting fine hats – his tall, hers broad – and adorned with jewellery and lapel trinkets. Laughing, sipping champagne from a couple of coupe glasses, believe it or not.

Chin-chin!

Look at that view, Claudine!

Just sublime, Henry!

A very dapper pair they are, unlike the usual dirty-shirted, field-gleaning, sheep-shouldering citizens of the vale. Mad aristos who are, irrefutably, flying. They’ve done it; they’ve freed themselves from gravity; conquered the exclusive upper zone. Helm’s not quite sure how Helm feels about it.

There’s an unusually unpleasant burning smell coming from the undercarriage: wool and charcoal smouldering in a lethal-looking kettle, hot tongues licking at the base of the – new word for Helm – balloon. The woman says it, her voice sharp and silvery as cutlery in the heavens; anxious – well, who wouldn’t be.

Henry, darling, is our balloon sinking? Aren’t we descending a tad hastily?

Balloon.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Balloooooooon.

Ew.

We aren’t going to wreck, are we, Henry?

Claudine has a point. Surely it’s a little dangerous, the onboard fire propelling the flimsy-looking lung of fabric, under which the humans, who are observably prone to plummeting when met with pure unstructured atmosphere, are now kissing. Goosing, actually, for Henry’s free hand is sliding down the stayed waist of the fancy frock to the beskirted bottom of Claudine, and groping about its layers, and gathering them upwards to reveal stocking tops and flocked bloomers, while his other hand holds the sloshing coupe. (Such is the masculine form of reassurance.)

Helm, meanwhile, is astounded, processing. Wasn’t expecting this business anytime soon. Helm is used to humans swarming about below on terra firma, jumping not very high compared to, say, a lynx or a frog or a buck. Hitherto they have not had much luck with wings, or chutes, or floats, throwing things up that rapidly come down, arriving in abrupt mush at the bottoms of cliffs – haha. Who knew that one day they’d learn the trick. Which ingenious inventor fashioned this impossible flying trinket? (The clever Scot, Cameron, did, having adapted a design from the Montgolfiers: this one’s been inflated near Langholm, has travelled the length of Cumberland and is, though novel in these parts, a very imperfect and soon-to-be-defunct breed, replaced by propane-and helium-fuelled versions. Cameron himself no longer flies, having crashed the previous balloon, having been – full disclosure – dragged three miles in a tangle of rope and silk, then tossed off the woven platform and hurled against an oak; several lower vertebrae fractured, resulting in a stiff gaited limp plus a nightly dependence on opium. He still likes to send his chums up, though, if they’re game enough.)

The balloon draws alongside the summit, level, almost, with Helm. Its basket creaks a fraction under the weight of flesh and bone. The bubbles in the glasses tingle – 1812, imported from Aÿ: not a bad vintage, though fusty, a little semeny, thinks Claudine, who may simply be thinking ahead.

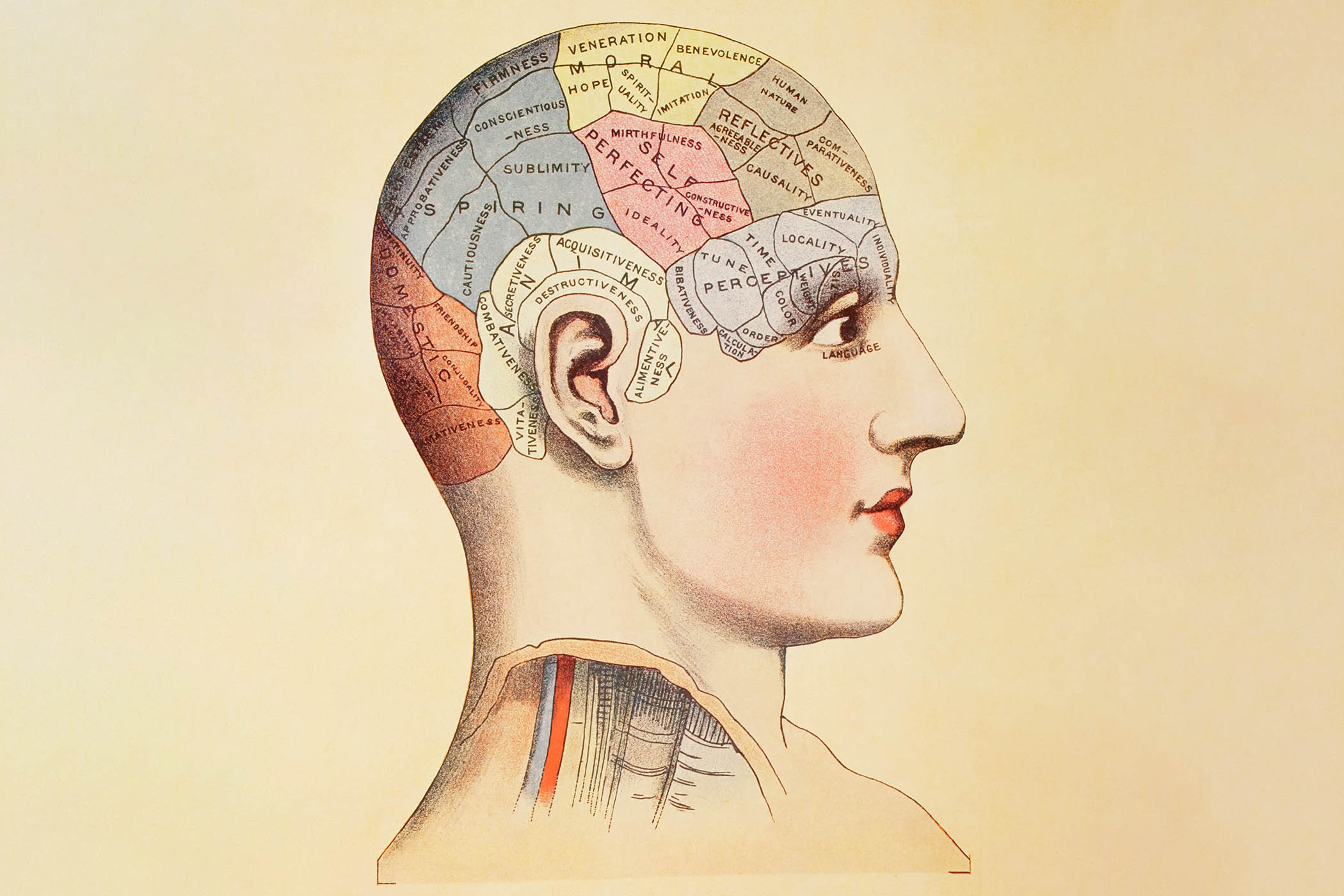

There they are, the exuberant, flamboyantly dressed couple, petting beneath a gargantuan inflammable. Helm is buoyed by the aerial company, and oddly nauseated. Something about the creepy, crêpey surface of the inflatable, and the oo of the balloon, and the balloon itself, its potential to burst and issue forth a loud, deflationary, unfunny raspberry. Cue, globophobia. (Just wait, those smaller, rubbery plastic ones are really going to twist Helm’s melons, accidentally let go of by children at parties, squeaky, sticking to hair with static and popping without warning, leaving withered, foreskinny cases behind – it’s all shudder-inducing.)

There is the temptation to gaily blow the thing across the valley, to send it off, waffling and spinning. Except even more thrilling is the peep show at which Helm has a front-row seat. For Henry has now tossed the empty bottle of champers and his glass over the side of the basket (Mind out below, sheep!), in order to use both hands on Claudine, to get inside the bloomers and rummage gently and insistently in a way she simply can’t resist; to release his trouser buttons and draw out his slightly convex pink spigot with its bead of lubricant at the tip (bizarre apparatus really, see how it nods and bounces, how it salutes), while Claudine, crackling with panic or adrenaline or arousal, is sipping off her champagne and gripping the nearest crown rope.

I feel you are amenable to love, my love, oh yes, splendid, I do feel it most specifically here. Shall we just die together?

Why not? They are blissfully alone in the clouds (almost). They are bright as birds. There’s such death-wishing effervescence in Claudine’s brain she will agree to anything, any dangerous act of congress, an orgy with the celestial masses possibly. She too tosses her glass overboard and it sails downwards, glinting, faceted, brittle, exploding its crystal bomb on the limestone below. She adjusts her stance. Henry lowers the garment to reveal a frazzle of pubic hair, with a damp twist, then performs, with murmurs and groans and a kind of daring unstoppability, the first-ever act of the mile-high club – more accurately 3,500 feet and sinking steadily. Sinking rather rapidly. Claudine is not wrong, for the upper silk stitching has loosened and hot air is rushing through the gape – putting them on a trajectory that will lead to a rather undignified but unfatal landing near Soulby, in the crook of the meandering, soon-to-be-christened Scandal Beck, to the astonishment of both the villagers and the minnows, and luckily only half a mile from the house of Robert Hutton, bonesetter.

Until then, Helm, through no fault of Helm’s own, goggles at the pair in gross detail. Henry circles his fingertips and sucks Claudine’s earlobe. Claudine releases the rope she is gripping, holds on to her magnificently feathered hat, and ohs and ahs, her décolletage flushing as she climaxes. Henry courteously grants her a minute of breathless recovery, cheek to cheek, before helping her kneel in the wicker gondola and mouth at his ridiculous apparatus until he, too, expleting and juddering, calls out, God’s body!

The lady rises and delicately spits out the whitish product. It rains onto the Pennines.

Ballooooon.

Sarah Hall’s novel, Helm, is published by Faber & Faber on 28 August. Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £18. Delivery charges may apply.

‘The wind was like a childhood friend’: read Erica Wagner’s interview with Sarah Hall.