One beach looks much like any other. Would you agree? In autumn 2019, on a writer’s residency in Cascais, a Portuguese coastal resort, I spent hours on Guincho beach. The summer surfers were gone. The wind kept all but the hardiest walkers away. I would wander from one end of the beach to the other, as fragments of dialogue and glimpses of possible episodes in my novel began to reveal themselves to me. I came to love the beach, to feel myself entirely at home there, at one with the whistling sand, the tireless wind and the grey waves breaking on its shore. I would be lying if I were to say that first glimpse of the beach had given me a Proustian jolt of realisation. And yet, even though it would take me another couple of years to make the connection, I did know this beach. I had seen it before, almost exactly 50 years earlier. And seeing it back then, witnessing the drama that had taken place there, had been one of the most powerful and formative experiences of my young life.

It was early in 1970 and I was eight-and-a-half years old. I lived with my parents and my brother on the Lickey Hills, a famous beauty spot a few miles south of Birmingham city centre. One rainy Saturday afternoon, my parents took me and my brother to the cinema in the market town of Bromsgrove to see a film called On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. My sense of anticipation was high, but I didn’t really know what I was in for. I knew that this was the latest in a series of films about a British spy called James Bond, and my parents were crazy about them and their star, Sean Connery. I also knew that one of the special things about this new film was that for the first time there would be a different actor playing James Bond. His name was George Lazenby and my parents seemed deeply sceptical that he was going to rise to the occasion.

The four of us settled into our seats. In my (no doubt unreliable) memory, the auditorium was full, and the air was muggy with heat rising from the damp, chilled bodies of hundreds of expectant punters as they began to warm up together in the dark.

On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is unusual among James Bond films in that it sticks closely to the source novel: the opening 45 minutes or so are preoccupied with Bond’s blossoming romance with the Contessa Teresa di Vicenzo (Tracy, for short) and there’s hardly any action or suspense to speak of. Nothing really happens, in narrative terms, until Bond arrives in Switzerland and starts tracking down Ernst Stavro Blofeld and his mountain hideout.

Except, of course, for the pre-credits sequence: the first few minutes I ever spent in the company of James Bond, which remain indelibly stamped on my memory.

At the very start of the film is a short, incomprehensible dialogue scene between Q, M and Miss Moneypenny. But the scene that everybody remembers as the real beginning of the film follows straight afterwards. A coastal road, a handsome man, an Aston Martin driving at speed, and (for the first time) music – irresistible, pulsing, sinister music. (On Her Majesty’s Secret Service features John Barry’s best score for the Bond films; and indeed, one of the best film scores of all time.) At once we’re in a world of pure adrenaline, and pure cinema. We are somewhere in southern Europe, judging by the scenery and the light. Bizarrely, the handsome man – James Bond – is wearing a trilby hat. Was this fashionable, in 1970? Surely not. A red sports car overtakes him, cuts in front of him, and then tears off ahead. It is being driven by a beautiful woman – Tracy herself, we will shortly learn, in a role interpreted, with characteristic perfection, by Diana Rigg. Naturally, Bond is compelled to give chase. According to the novel, they’re both driving along the winding, vertiginous road at 125mph: in the film, therefore, it goes without saying that Bond soon takes one hand off the steering wheel in order to light a cigarette. We see him puffing away on it in extreme close-up, the centre of the screen filled by the dimple in his chin.

George Lazenby as James Bond, and Diana Rigg as Tracy

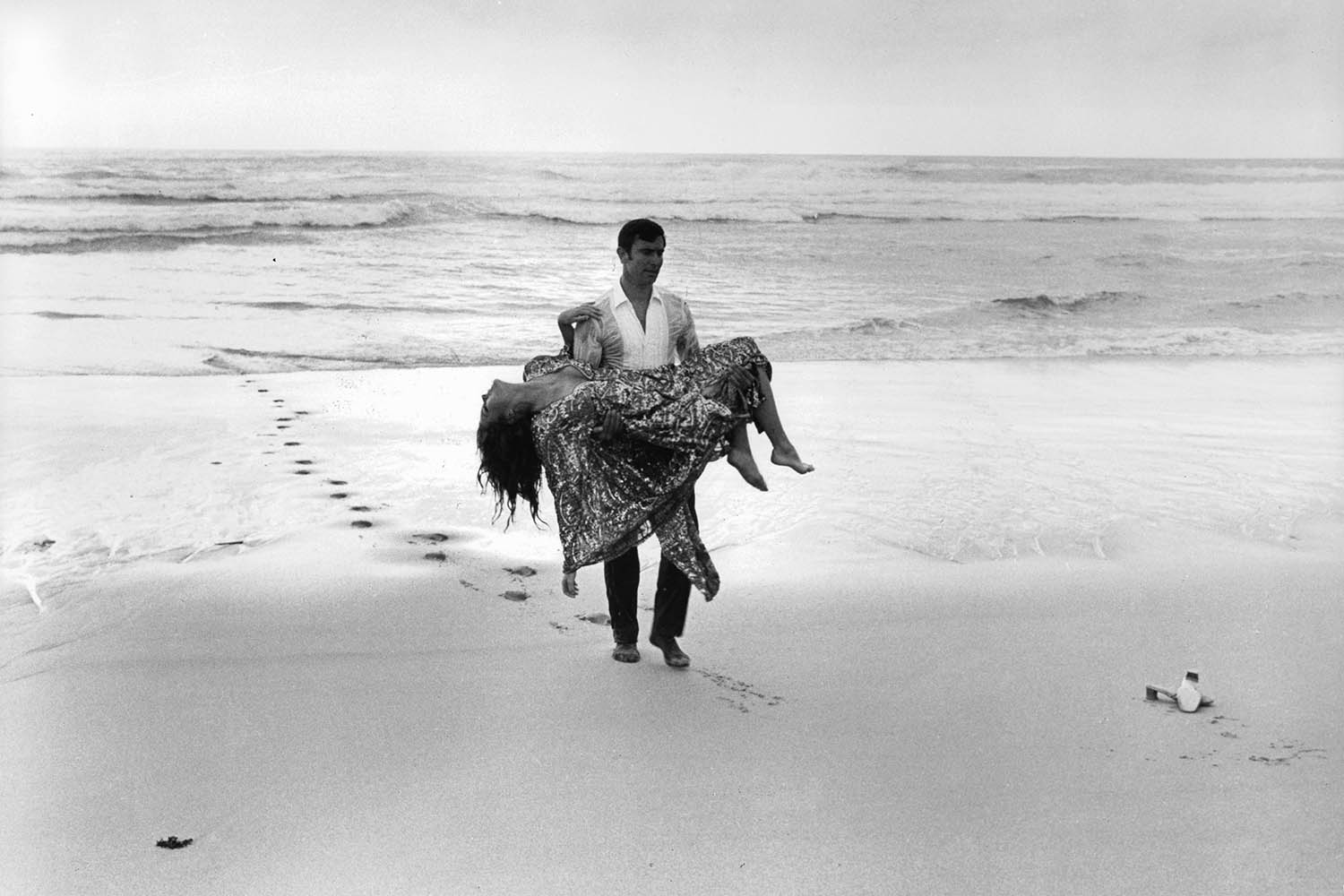

Soon, Tracy’s car pulls off the road and comes to a halt on a patch of scrubland above a beach. She jumps out and runs down to the water’s edge. Bond pulls up, opens his glove compartment, picks up the telescopic lens from his sniper’s rifle and puts it to his eye. Our next view of Tracy is in Bond’s crosshairs, as she kicks off her shoes and walks into the sea. The sky is a muted pink, the water is blue-grey and patterns of faint sunlight dance off the breaking waves. (It’s magic hour, but is it meant to be dawn or dusk? Dawn, I think.) As soon as he sees her entering the water, Bond knows that she’s in trouble – this is a suicide attempt – and swings into action. No point in running after her: that wouldn’t be nearly dramatic enough. Instead he kicks his Aston Martin into gear and drives it right up to the water’s edge, skidding and swerving on the sand. Must have saved a good three seconds that way. Out he gets, off with his hat (you lost a couple of those seconds there, James) and splashing into the waves he goes.

Soon he has Tracy in his arms and is carrying her recumbent body out of the water, the rising sun in the background. Maybe this is the image that has stayed with me most strongly all these years, giving perfect cinematic shape and embodiment to the idea that what women really want is not – as Tracy’s father will insist a few scenes later – to be “dominated”, but to be rescued. This idea will imprint itself upon my eight-year-old brain, and come to define (if I may allow myself a moment of auto-analysis) many of my adult relationships. Anyway, Bond’s sense of heroic triumph is short-lived, because no sooner has he laid Tracy down on the sand than two heavies appear, one armed with a gun and the other with a knife; and yes, I wouldn’t have thought this possible, but the scene is about to get even better. The music starts up again – more jagged, this time, more urgent and dramatic – and within seconds the three men are beating all hell out of each other. They fight on the beach; they fight in the water; they get tangled up in fishing nets and cause abandoned fishing boats to collapse on top of them; they perform judo flips; they exchange grotesquely amplified blows to the face and head; they sock each other in the jaw and in the stomach. It’s the most exciting thing I have ever seen or heard. Of course, Bond ends up knocking both of his assailants out cold, but by then it’s too late: Tracy has driven away, disappearing in a cloud of dust. She has not offered Bond so much as a word of thanks for saving her life.

Bond takes it on the chin. He could easily have rushed back to his Aston Martin and set off in pursuit once again, but this time he doesn’t bother. This time he just stares wistfully after the receding sports car, and then he says something. He could be talking either to himself or to us, the audience sitting out there in the dark – it’s impossible to tell. Either way, what he says is amazing. He allows himself a rueful half-smile and says: “This never happened to the other fella.”

Even though I have never actually seen Bond played by “the other fella”, I get the joke at once, and think it’s the coolest thing I’ve ever heard. Already, without knowing the phrase “fourth wall”, I’ve become a fan of comedy that breaks it (above all Monty Python’s Flying Circus, which had started broadcasting just a few months earlier, on 5 October 1969). What I love about this joke is the way it makes Bond and the audience complicit, drawing them into a thrilling and unexpected intimacy. I love its insolent honesty, too: the way it acknowledges the real world, the world outside the film.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The last hour and a half of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, set amid the snowcapped mountains of Switzerland, gave me a lifelong fascination with skiing and winter sports which, sadly, translated more into weekly viewings of Ski Sunday from the safety of my parents’ living room than into any Bond-like proficiency on the slopes. I remember the intense romanticism of the sequence where Bond, exhausted and badly shaken after his nocturnal escape from Blofeld’s headquarters – with Lazenby showing a human vulnerability that Sean Connery would never have allowed himself – looks up to see Tracy standing in front of him on the ice rink. The relief on his face, the incongruous song playing over the Tannoy (Nina van Pallandt singing Do You Know How Christmas Trees are Grown? – because this is Christmas Eve and On Her Majesty’s Secret Service is, among other things, a Christmas movie, and one which I much prefer to It’s a Wonderful Life). Their beautiful snowbound night together in the isolated barn, and then the resumed ski chase the next morning, with the horrible scene of the man falling into the path of the snow plough so that the snow shooting into the air from its chimney becomes crimson with his blood and guts. All of this stayed with me, vividly, in the decades between my first viewing of the film and my revisiting it.

There is something else, though. My introduction to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service came at the time in my life when I was just beginning to write stories of my own. I was starting to learn the ropes of putting together a sustained narrative. I wasn’t a bookish child and I didn’t come from a bookish household. My parents’ favourite authors were Arthur Hailey and Agatha Christie. The first things I wrote were detective stories using characters stolen from a strip in Lion, a weekly comic. Up to that point, On Her Majesty’s Secret Service was probably the most sophisticated piece of narrative art that I’d encountered. I was at an extremely impressionable age. And I think now – looking back, 55 years later – that it affected me in a profound way.

In November 2024 at a book event in Rome, a man put his hand up and asked me this: in almost all of your novels, he said, you tease the reader with the possibility of a happy ending. Then, in the final chapter, or even in an epilogue, you pull the rug out from beneath us, and leave us with an ending which is at best ironic, at worst dark and pessimistic. Why do you keep doing it?

I thought about this for a few moments. Was there really such a pattern in my work? What a Carve Up! – yes, it happened there. The Rotters’ Club – yes, in the very final few words of the novel. The Rain Before It Falls, The Terrible Privacy of Maxwell Sim – yes, both times. Expo 58 and Number 11, definitely. This guy had really hit upon something. And why would this be? Why am I compulsively drawn to this recurring technique?

Well, the reason is obvious by now, surely. It all comes back to On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

‘Proustian jolt of realisation’: novelist Jonathan Coe

We all know how the film ends. Bond has uncovered Blofeld’s plan to destroy the world’s food supply with a sophisticated form of germ warfare. The plan will be carried out, unwittingly, by Blofeld’s “angels of death”: the group of beautiful women who’ve been staying at his mountaintop clinic to have their allergies cured, and who’ve now been sent home with radio transmitters hidden in the makeup sets they’ve all been given as Christmas presents. But with the help of Tracy’s father, the clinic has been blown to smithereens, and Bond has pursued Blofeld down the bobsleigh run in a final, unbelievably exciting chase sequence, at the end of which Blofeld’s neck gets caught in the cleft between the branches of a tree and we assume that he has been killed – in a suitably nasty way.

All that remains is the happy ending: the wedding of Bond and Tracy. It takes place in a setting of sundrenched Mediterranean splendour, with M and Q in avuncular attendance and Miss Moneypenny on hand to cry bittersweet tears of either happiness or, more likely, suppressed romantic unfulfilment. Bond and Tracy drive off on their honeymoon. But their happiness lasts for minutes rather than years. Stopping by the side of the road to take the decorative flowers off their car, they are ambushed by Blofeld and his sidekick, Irma Bunt, who shoots off a round of machine gun fire in their direction. Bond survives; Tracy is killed. And the final, heartbreaking image of the film is of Bond cradling his dead bride in the car, having just told a policeman that everything is OK because she is “just resting” and they have “all the time in the world”. (Again, Lazenby acts the scene superbly, perhaps better than Connery would have done.)

I don’t recall that this ending flattened me at the time. At the age of eight, my takeaway from the film was not its emotional content but its glamour, its action, its frenzied kinetic energy, its violence. But, perhaps in a deeper or more abstract way, I absorbed something else from On Her Majesty’s Secret Service that day, something I would go on to mimic in most of what I would write when I became a novelist: its narrative shape. The compulsive undercutting of every potential happy ending, and its replacement with something darker.

And what about Guincho beach? It was only two or three years ago, when my daughters bought me Charles Helfenstein’s book The Making of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service as a Christmas present, that I realised the film’s opening fight sequence – the scene that had set so much in motion, that had done so much to define me half a century ago – had been filmed in Portugal, a few miles north of Cascais, on the very beach where I’d taken so many solitary walks back in the autumn of 2019. Surely, in the depths of my subconscious, I should have known that, while pacing that sandy immensity, I had been walking not just figuratively but literally in the footsteps of George Lazenby? In the end, I reconciled myself to the idea that it had been no more than an eerie coincidence, and I should be satisfied with that. One beach, after all, looks much like any other.

Jonathan Coe’s novel The Proof of My Innocence is published by Viking. A version of this essay appears in The Carbon Arc, a new collection of writing about cinema published by Vanguard Editions

Photographs by Getty Images