Related articles:

I seem to have spent years in archives. I seem to be endlessly drawn back to them, to places of beginnings and places where stories end. These are archives with filing cabinets, microfiche, with ledgers on shelves, with manila envelopes of photographs and carousels of books, letters and receipts and wills and photographs and account books.

Lists of acquisitions and lists for deportations, catalogues of objects and the lives of those who owned the objects. I try to make an appointment and hope someone will reply.

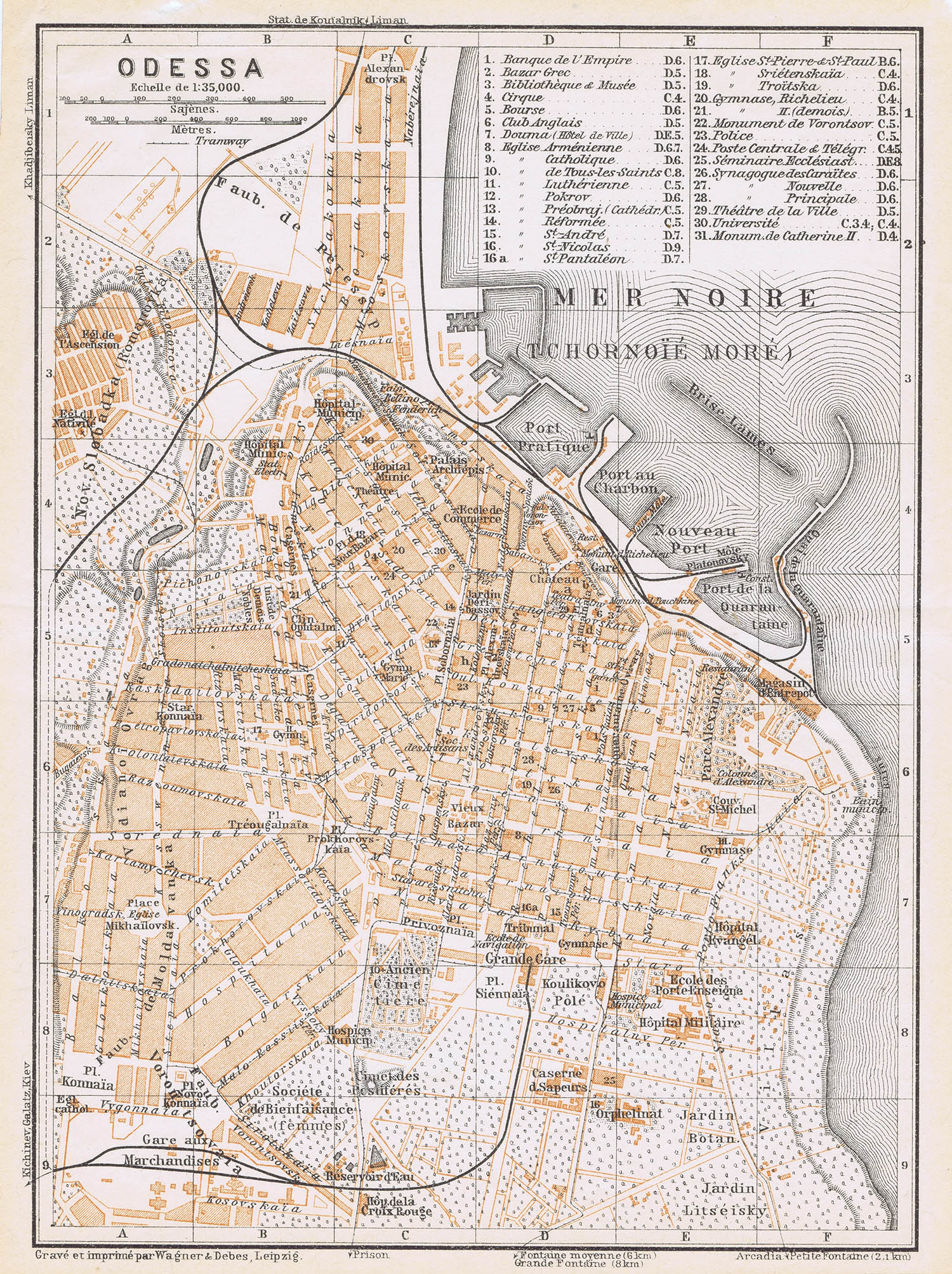

Author and potter Edmund de Waal photographed for the New Review in his London studio

I walk in and find some kind of chronology, some appearance of lucidity, legibility. Someone has tried to map X, order Y. It all feels possible. I keep coming back, notebook in hand. I have spent the last year creating a book about archives that is itself archival, a gathering together of my reflections on archives from more than a decade. It is chronological. But when I read the book back, I find that this reveals not a linear progression in my thinking but a stubborn cyclicality: the first and last written texts of the book are encounters with my own family archives. I start in Odesa in 2009 and end in Paris in 2021. And in between are my responses to the archives of poets and artists and places I love, of porcelain and pencil and fear.

Perhaps the most deeply hidden motive of the person who collects can be described this way: he takes up the struggle against dispersion. Right from the start, the great collector is struck by the confusion, by the scatter, in which the things of the world are found.

Perhaps the most deeply hidden motive of the person who collects can be described this way: he takes up the struggle against dispersion. Right from the start, the great collector is struck by the confusion, by the scatter, in which the things of the world are found.

Walter Benjamin

My book is formed in three parts. It is a mapping of the archival impulse of return. So I begin with the return to Odesa, where my family started out. I return to the places of my father’s childhood to try to find out what happened.

I return to Berlin, to Paris, Tokyo, Stoke-on-Trent. To Bologna to watch the light change in the dust of Giorgio Morandi’s studio on Via Fondazza. I find myself in the archives of the ceramic collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, tracing who acquired the porcelain, and in the stores of broken objects of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, tracing why those things are hidden away. I try to track the route [the great German-Jewish philosopher] Walter Benjamin took on his walk to school in Berlin in 1903, what he was reading in the summer of 1938. I need to know what a Parisian cousin of my grandmother’s gave his friends for dinner between the wars. If I know this, if I can hold this letter and find its reply, turn the pages of the morning newspaper, run a finger down the lists of applications for visas, then – I believe – I can start to piece it all together.

And in the gaps between the catalogued, here are the spaces where the letters have vanished, the crossings-out, the redacted. I keep coming back to the image of the ragpicker, the salvager of the detritus, unloved, overlooked, central to Benjamin’s thinking about archives. He used the idea of the scrappy – verzetteln was his word of choice, a word that holds both “failure, fragmentary, unachieved” and “the particular method of making information manageable”, as the Benjamin scholar Erdmut Wizisla has noted.

Archives cross all the senses. They are tacit, digital, somatic, auditory. They are places of memory.

On my journeys through archives, I found, again and again, fragments of text used as bookmarks, unmoored photographs with no description attached to them. These have often been the most generative moments of discovery. For this reason, the illustrations in an Archive are not anchored to their captions.

Related articles:

I hope that they feel like they have been tucked into a book and forgotten. There is the element, in any archive, of trespass. Am I allowed in? What is my responsibility to the people who have been here before? How do I respect the dead and their integrity, their individuality and separateness from me? Is archiving – the act of it – a technology of violence as well as preservation? What is excluded, suppressed, forgotten?

I question what I am doing with these family archives, and my own – the many thousands of books in my home, the archive room in the studio with pots going back to my very first, from the 1970s.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

There’s an archive of broken pots in the library; a shelf of shards. Part of the family archive has gone to the Jewish Museum in Vienna. I have handed my ceramic archives on to the Victoria and Albert Museum.

And I find that difficult. Difficult because it is a ceding of control. I cannot now call things back and throw them away. This book is me not throwing things away.

A 1911 Baedeker map of Odesa, where the author visited in 2009 to trace his family’s history via archive material

Fragments: In Odesa

It is November 2009 and I need to go to Odesa. I am writing a book on memory and touch, based around a collection of Japanese netsuke [miniature sculptures] and the family houses they were in. I am trying to trace a part of a family story. It was a book [The Hare with Amber Eyes] that was supposed to take me a year. I am starting my third year. Months have unspooled in archives looking at the scribbles in the margins of books, the letters used as bookmarks, the photographs of 19th-century cousins, the Odesan patents.

I have a thin file from my father with a family tree and the envelopes that he found at the backs of drawers with their thin shake of a few sad aerogrammes. Weeks have gone on the walks through Paris and Vienna and Tokyo, tracing the places where the family lived. I stand in streets in front of their houses and wonder what I am doing finding routes across cities, an old map in one hand, lost.

I’m sick with it all. My fingers are tacky from papers and from dust. My father keeps finding things that he thinks will interest me. He has just found a diary in unreadable German from the 1870s that I need to translate. A week goes by in an archive and all I have is a list of unread newspapers, a note to look up some correspondence, a question mark about Berlin. My studio is full of books. I am a potter and I haven’t made any porcelain for months and months.

Perhaps if I stand in the house in Odesa where my great-grandfather Viktor was born I will understand. I am not sure what I will understand. Why the family left? What it means to leave? But it feels imperative. I am sure that this will provide my book with an ending.

Some traces are archival. Below the opera is the Angliisky Klub, the English Club where a cousin was elected “by acclamation” to be the first Jewish member, a move so radical and unexpected that it is mentioned in the newspaper. This is the place on the boulevard where an aggrieved merchant pulled a revolver on my great-great-grandfather outside his house, and where he was overpowered. Somewhere down that street between the catalpa trees is where the disinherited Stefan Ephrussi [Viktor’s brother] lodged with his new wife, his father’s mistress.

Some traces are more concrete. After one of the pogroms, the brothers founded an orphanage. There is a school for Jewish children, endowed by Ignace [Viktor and Stefan’s father] in honour of his father, and supported for more than 30 years by new endowments. It is still there on the edge of a dusty park with feral dogs and ripped-up benches. Two low buildings slung together alongside the tramline.

In 1892, the school reports back on the 1,200 roubles given that year by the brothers. The school authorities have bought an astrolabe, a mezuzah, a globe, a steel knife for cutting glass, a skeleton and a demountable model of an eye. From an Odesan bookshop, they have spent 533 roubles and 64 kopeks and bought 280 volumes by Beecher Stowe, Swift, Tolstoy, Cowper, Thackeray and Walter Scott. With the remainder, there is money to purchase coats, blouses and trousers for 25 poor Jewish boys, so they can read Ivanhoe or Vanity Fair without shivering, covered up from the Odesan dust.

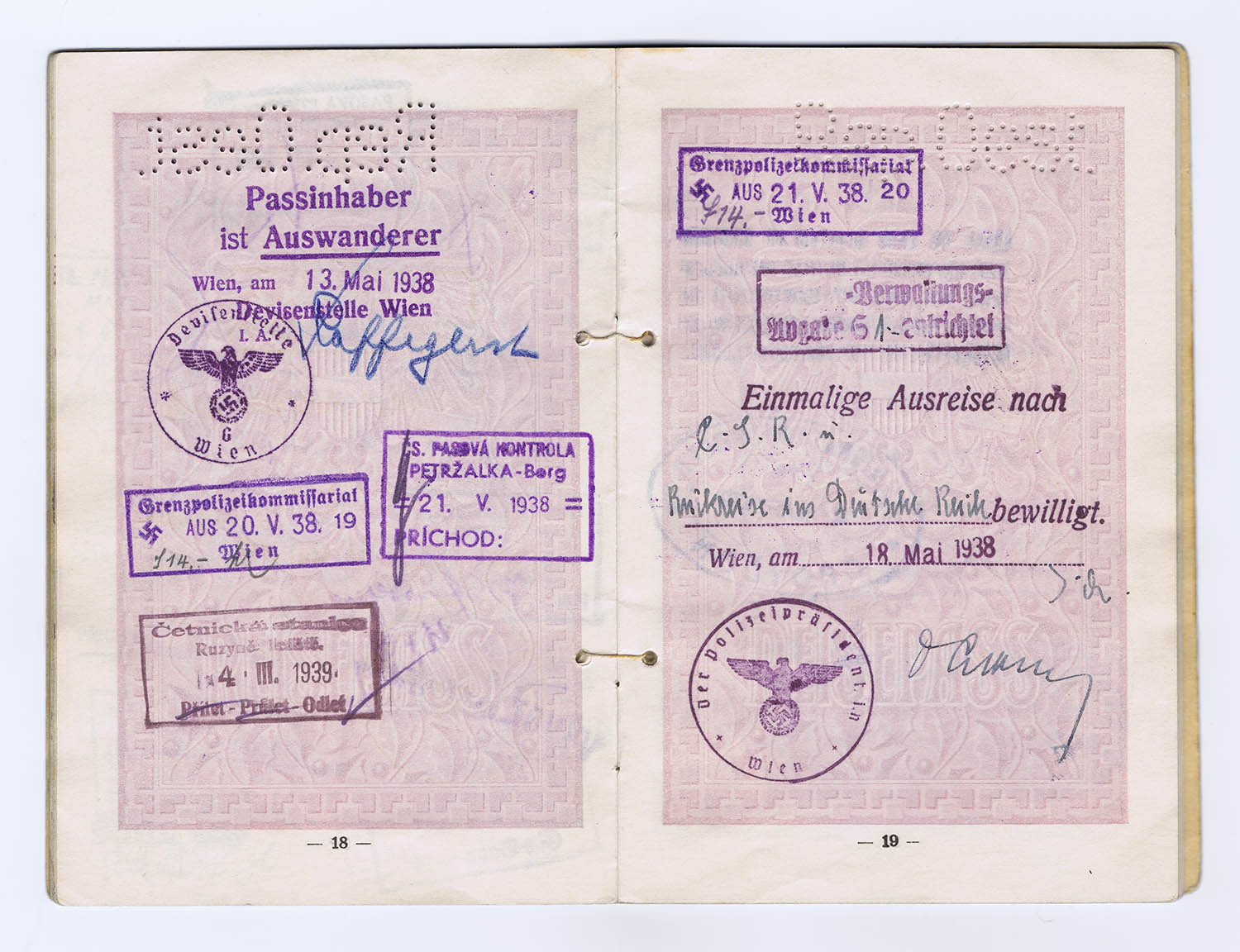

A passport from the 1930s belonging to the author’s great-grandfather, Viktor Ephrussi

My brother Tom and I meet Sasha, a small, dapper academic in his 70s... I tell him why we’ve come, that I’m writing a book about these small Japanese things, and he tells me politely that Maxim Gorky collected netsuke. We drink more coffee. I have brought an envelope of documents that I found in Tokyo in May in a stack of Architectural Digest. Sasha is appalled that I’ve brought them and not copies, but as I watch him he is like a pianist, playing with the different papers. There are records of Ignace as consul in Odes for the Swedish and Norwegian crown, an imperial notification from the tsar that he is allowed to wear a Bessarabian medal, papers from the rabbinate.

The desiccated records flicker into life as he moves them around. This is the old paper, he says, they changed this in 1870. Here is the signature of the governor, always so emphatic – look, it has almost gone through the paper. Look at the address of this one, the corner of X and Y! It is very Odesan.

This, says Sasha derisively, stubbing out another cigarette, is a clerk’s copy, poor writing.

My notebook is made up of lists of lists. Nothing coheres. Yellow Gold Red / Yellow armchair / Yellow cover Gazette / Yellow palais / Golden lacquer box / Titian gold Louise’s hair / Renoir: La Bohémienne.

Three days in Odesa and there are more questions than before. Where did Gorky buy his netsuke? What was the library like in Odesa in the 1870s? Berdichev was destroyed in the war, but perhaps I should go there too. Conrad came from Berdichev: perhaps I should read Conrad. Did he write about dust? There must be a cultural history of dust.

An Archive by Edmund de Waal is published on 17 June by Ivorypress, with a special launch event at the Warburg Institute, London WC1

Photographs by Edmund de Waal

Portrait by Antonio Olmos