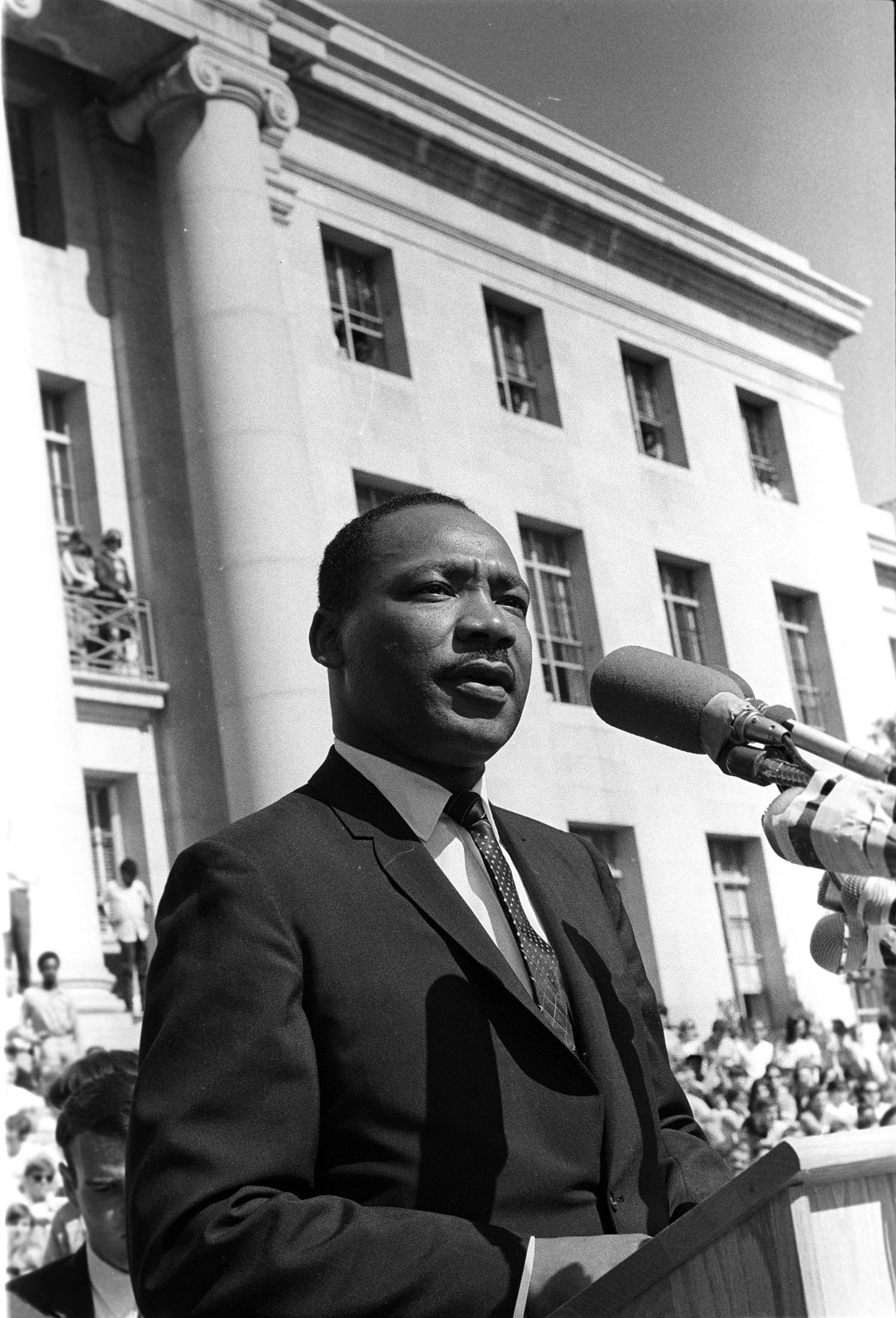

It has been exactly 58 years since the photographer Stephen Shames met Martin Luther King Jr, but he remembers the encounter as if it were yesterday. “I was just lucky,” he says. “I was in Sproul Hall, in the men’s room. And guess who was at the urinal next to me?”

It was 17 May 1967, and Shames was one among more than 7,000 people who had congregated at the University of California, Berkeley, to hear King speak out against the Vietnam war. After recognising the Baptist preacher out of the corner of his eye, he decided to tell King how much he admired him. “Men don’t talk to each other [there] – that’s a no-no. But when we were washing our hands, we started talking.”

King asked 20-year-old Shames, who grew up in Chicago, what he was studying. “From his point of view, here’s this white kid – is he a Ku Klux Klan? I’m sure he very quickly sized people up. He knew a lot of people wanted to kill him.”

Shames – who later became known as a photographer “who could get in anywhere” – realised that if they continued to chat as King walked to the podium to give his speech, the crowd would part to let Shames get to the front. “So we walked up together and I sat at his feet.” He took three or four shots of King from this vantage point. “I wish I had taken more. I didn’t really know what I was doing – I think it was the 15th roll of film I had ever taken in my life – but I knew it was Martin Luther King. And I knew I had to take his picture.”

By then, Shames had already decided he was going to be “the artist of the revolution” and document the work of anti-war and civil rights activists. A month earlier, he had taken his first shot of the Black Panther co-founder Bobby Seale after meeting him during an anti-war protest in San Francisco. “I was marching along and saw these two very charismatic Black men selling Mao’s Red Books.” Seale and his co-founder Huey Newton would buy the books for 35¢ in Chinatown and sell them for $1 a book, Shames says, which helped fund the Black Panthers after it was founded in 1966.

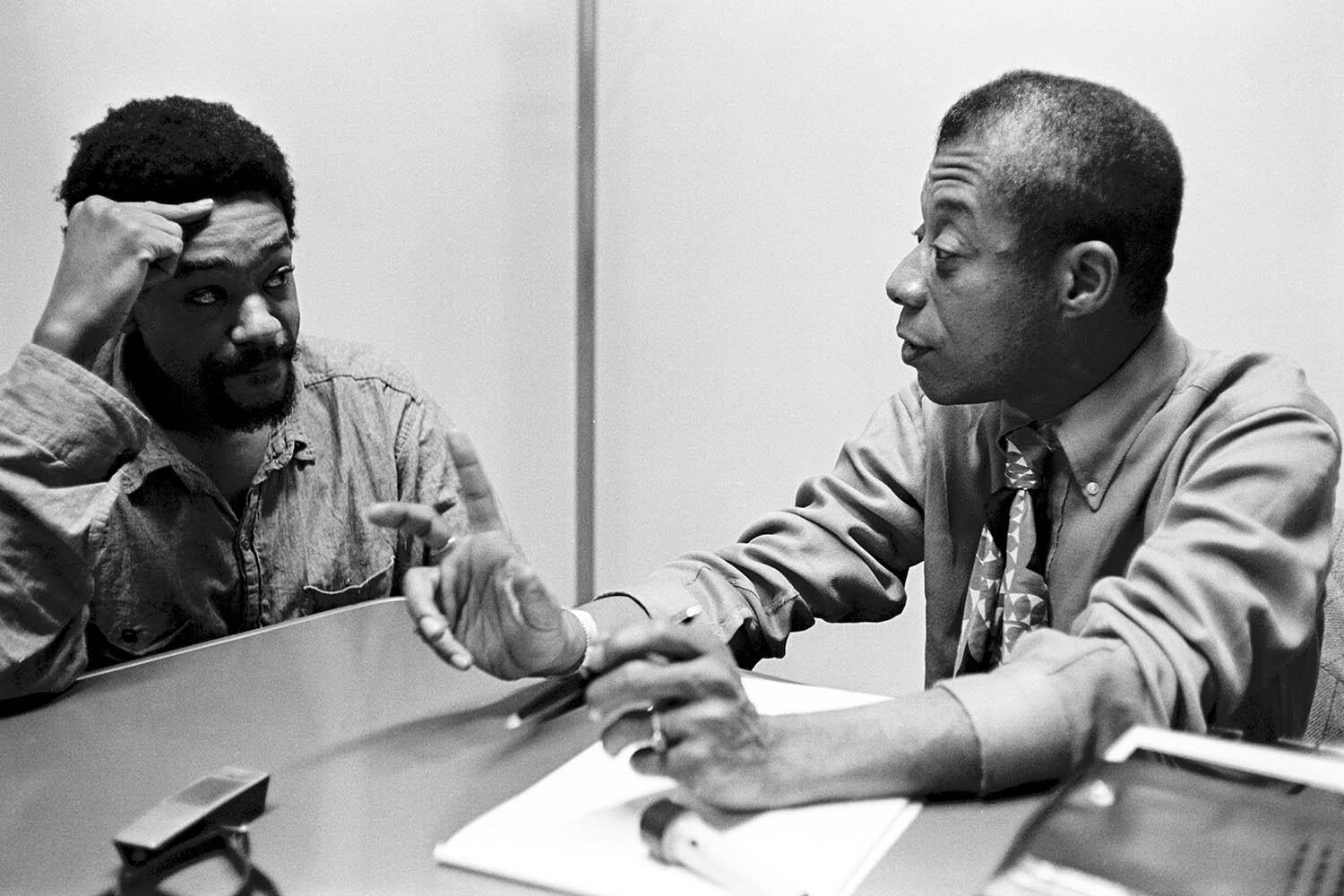

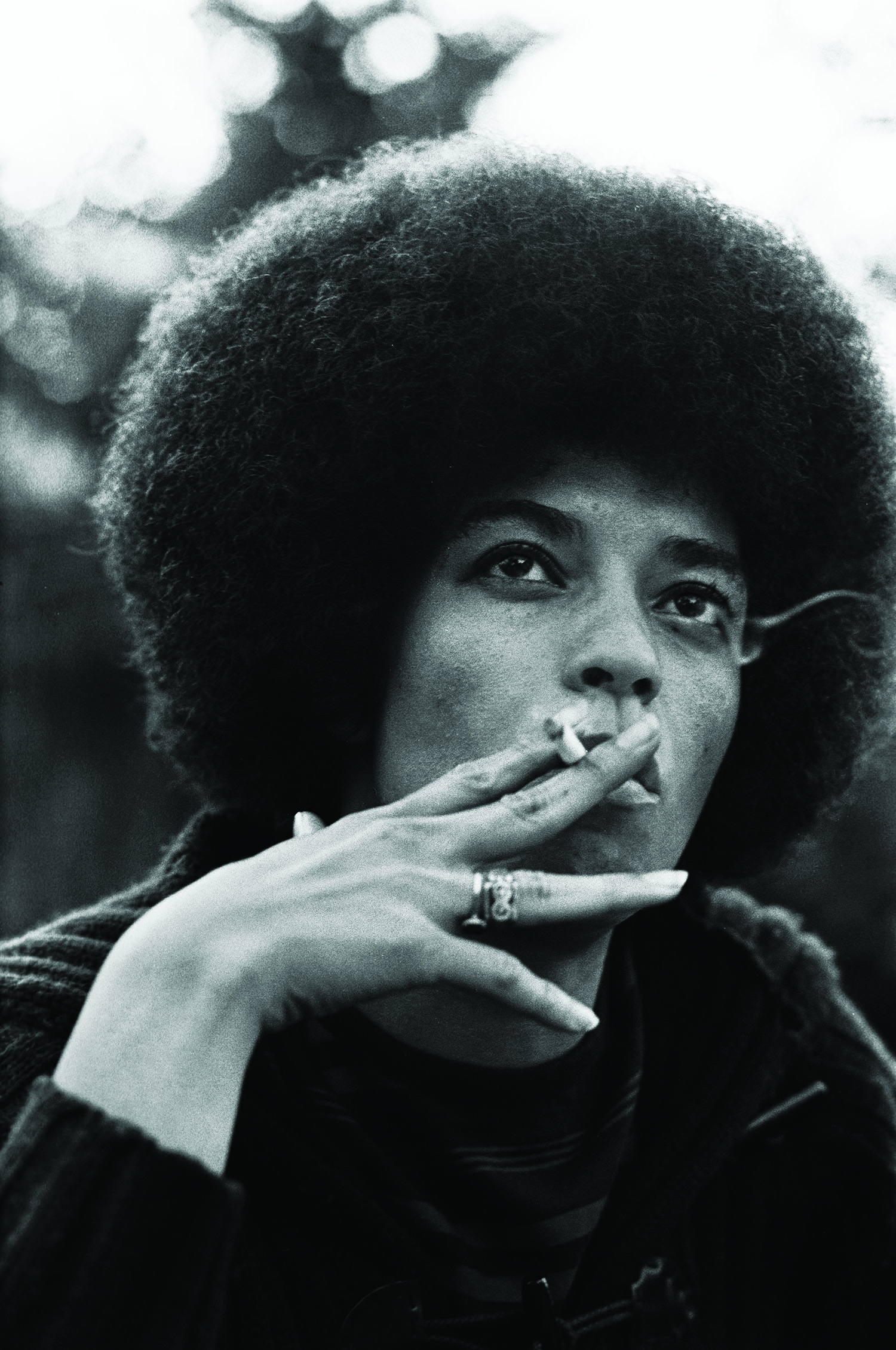

After the march, Shames visited the Black Panther office and showed Seale the photographs he’d taken. The two men embarked on a lifelong friendship that gave Shames unprecedented access to the Panthers and their high-profile supporters, including the activist Angela Davis and the writers Maya Angelou and James Baldwin.

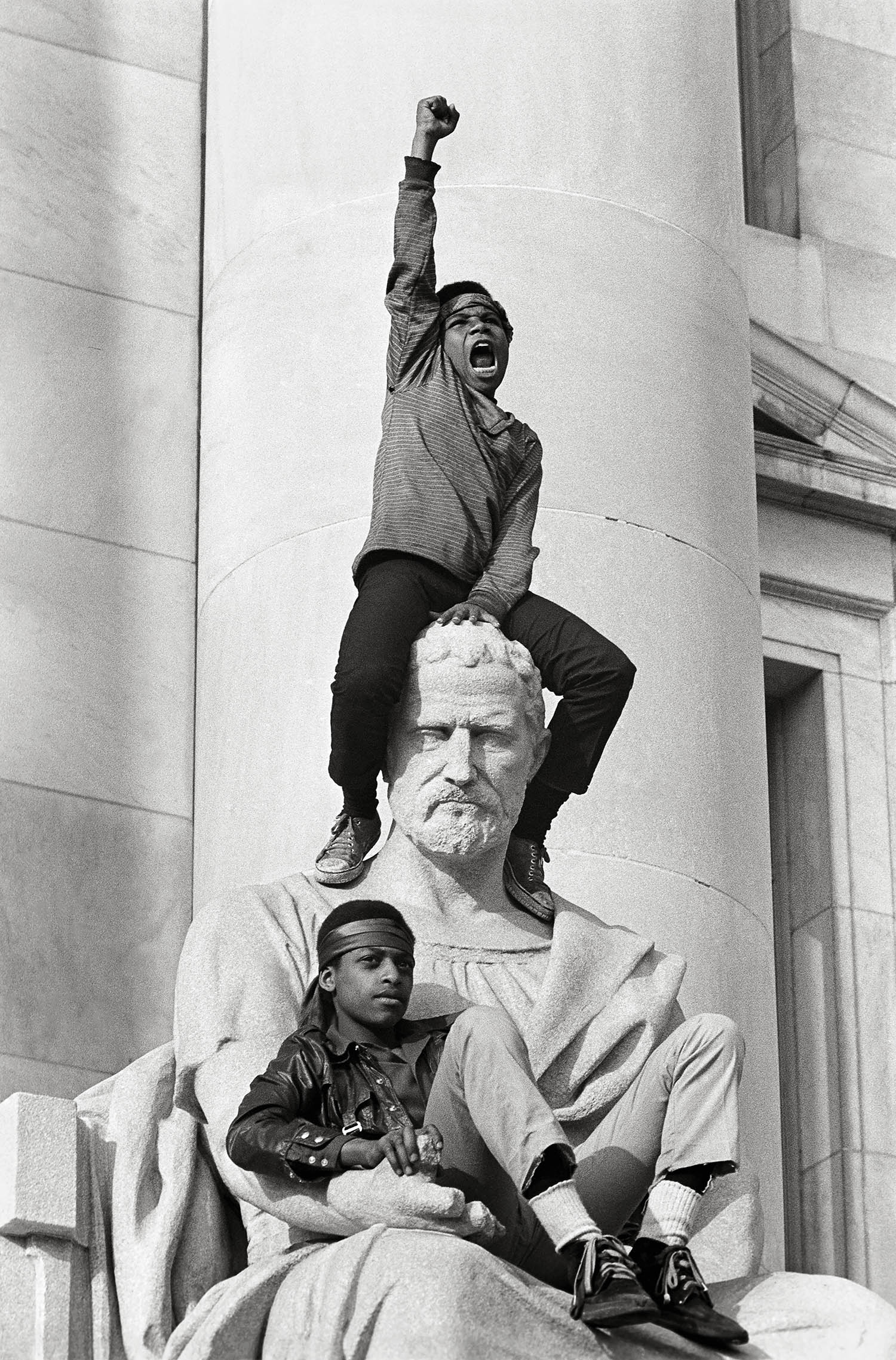

Shames, who is now 78, went on to take celebrated shots of young men at Black Panther rallies raising their fists in the Black power salute or standing in militaristic lines wearing leather jackets and black berets.

Black Panthers were basically saying: ‘We’re all humans and every human is equal’

Black Panthers were basically saying: ‘We’re all humans and every human is equal’

These iconic images of the civil rights movement now feature in the permanent collections of many international museums and art galleries. Yet some of the most intimate and revealing photographs Shames took that decade – such as his shots of King, and of Davis during her trial for conspiracy for murder – have never been exhibited.

Now these images will be displayed for the first time at a major exhibition, Black Panthers & Revolution: The Art of Stephen Shames, at the Amar Gallery in Fitzrovia, London.

They include poignant images of Baldwin visiting Seale when the latter was in jail awaiting trial for riot-conspiracy charges, which were later dropped: “That was their first meeting, and I got to sit in as the two of them talked,” says Shames. Baldwin and Seale also became lifelong friends, he adds. “I think that’s one of my favourite pictures I’ve ever taken.” Others show Afeni Shakur, mother of the rapper Tupac, as a young Black Panther, and Angelou beaming at a church congregation, her arm around a preacher as she fundraises for the movement.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

“The atmosphere at the rallies was very electric,” says Shames. “Bobby was a speaker on a par with Martin Luther King and Malcolm X – and he, Huey and Angela were like rock stars. They transcended being politicians.” They made young people feel empowered, he says. “Nowadays, I don’t think anyone thinks it’s ever going to get better. But back then we were very upbeat and positive, thinking: ‘We’re going to get out of this war, and we’re going to defeat racism.’”

One of the most striking photographs on display for the first time, which will be highlighted in a mural at the gallery, shows Davis smoking a cigarette after a tense meeting with her lawyers during her trial in 1972. She has a faraway look in her eyes. “They wanted to send her to jail, maybe execute her,” says Shames. “But she wasn’t the type of person who showed she was stressed. She was always strong. She was a leader.”

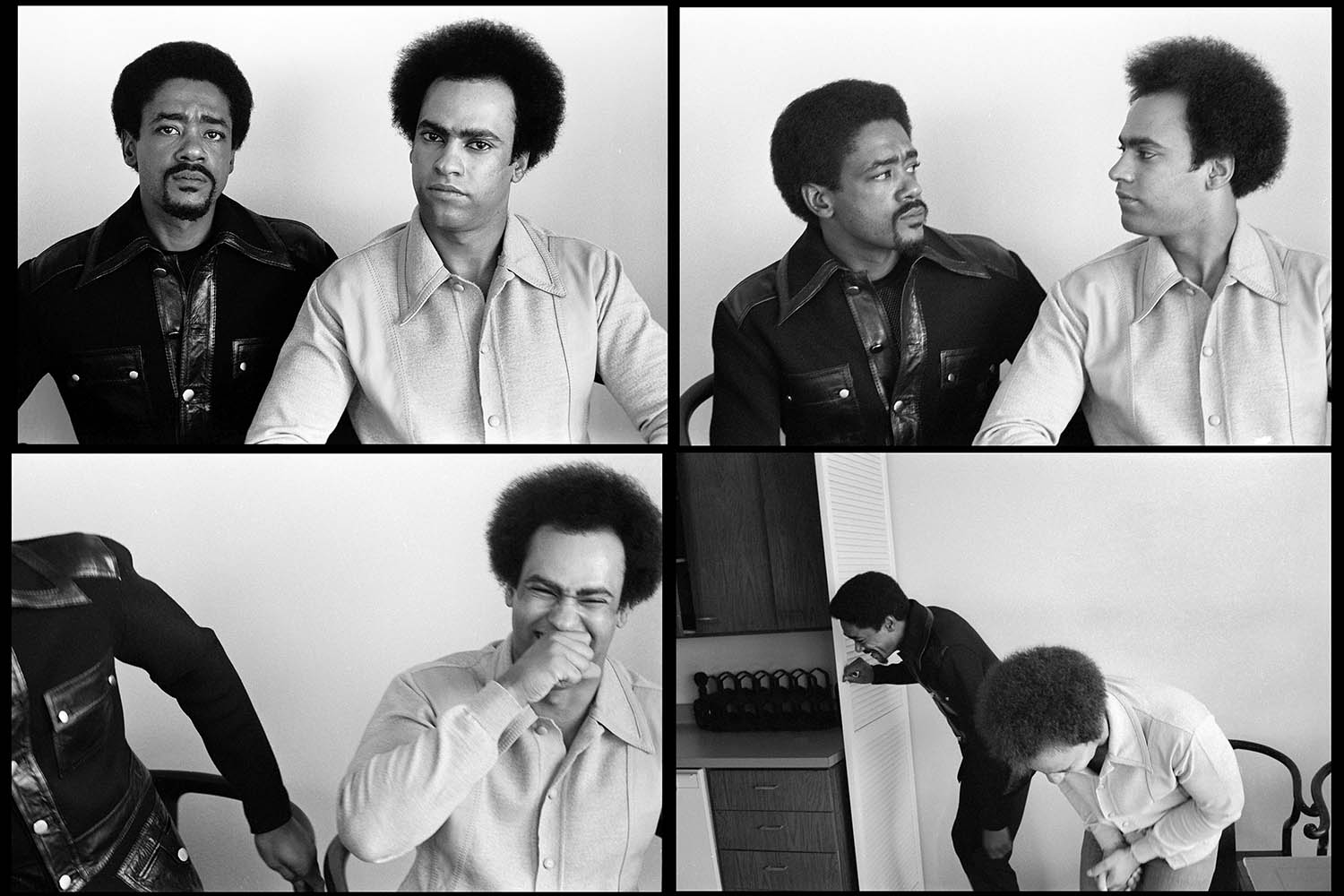

The exhibition will also include the joyful images Shames took of Davis when she was acquitted of all charges, as well as shots of Seale and Newton in which they erupt into fits of laughter. Shames hopes the images will show a warmer side to the Panthers than is typically displayed: “People have these stereotypes of revolutionaries. But the Panthers were people like everyone else.”

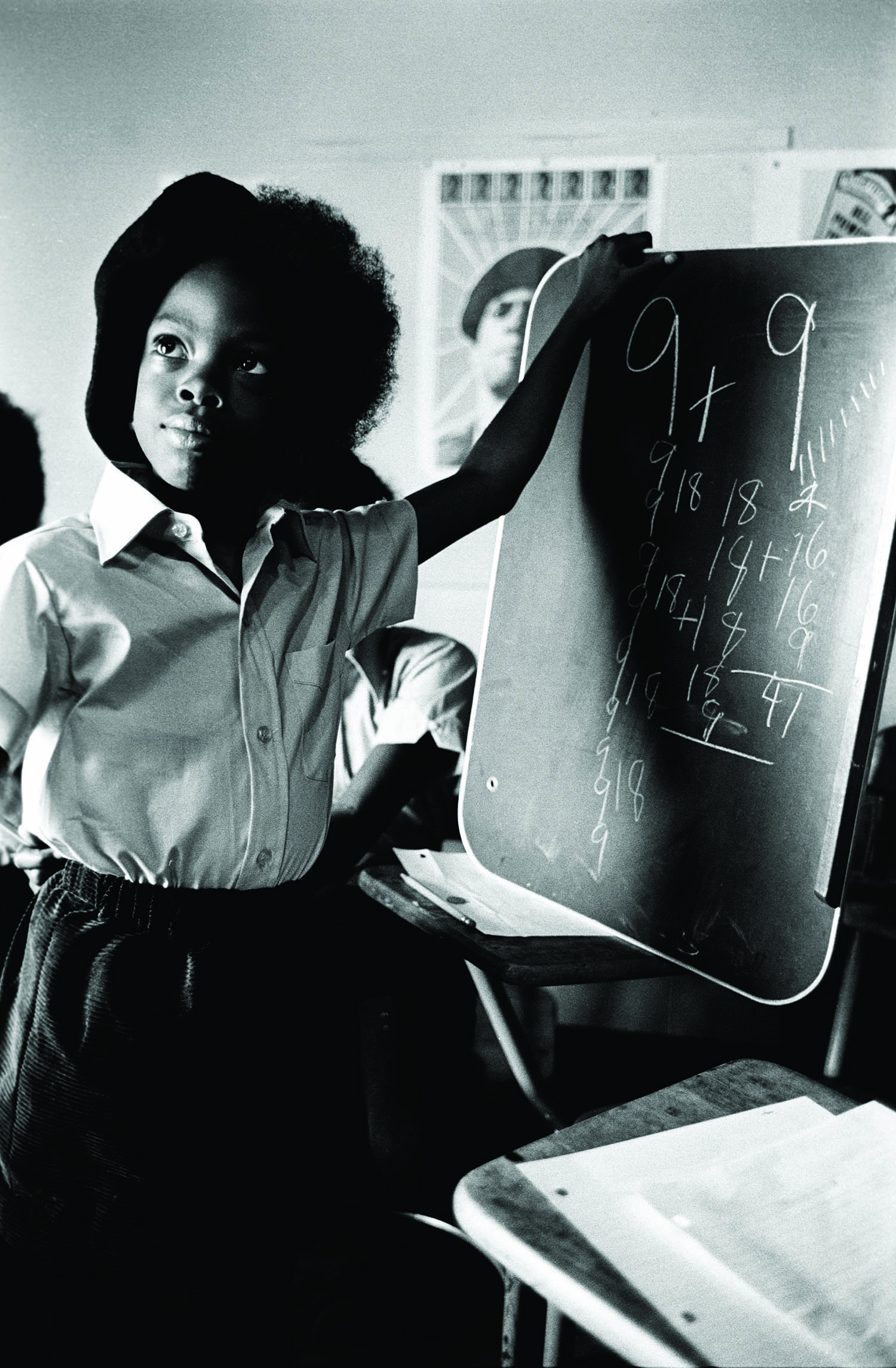

Some of his photographs of Black Panthers providing free food and educational children’s clubs are also being exhibited for the first time. “They had a free medical clinic. They gave away free clothing, free shoes – they ended up having 60 programmes,” he says. “I’m not saying they were all perfect. But the image that most people have of the Panthers is this false image the government created, the same way that Trump and the Republicans refer to Black Lives Matter or immigrants as if they’re terrorists. In fact, most of the shootouts people read about were initiated by the police.”

These photographs were considered too controversial to exhibit and print for decades, he says: one editor who wanted to publish a book of Shames’s Black Panther photos in the 1970s was fired for sending him a letter of intent. The project was then deliberately stonewalled by the publisher. “Very few people wanted to publish my Panther pictures back then. I got a few into the underground press and put the rest away.”

But eventually, “50 years later, history takes over and people look at things in a different way”, he says. Thanks to films such as Judas and the Black Messiah and The Trial of the Chicago 7, “the Panthers are mainstream now”. Shames was delighted when the Amar Gallery, which specialises in showcasing overlooked and underrepresented artists, approached him about putting on the exhibition. “Younger generations are looking at the Panthers with fresh eyes,” he says. It is now known there was a government programme, Cointelpro, which attempted to “discredit the Panthers and spread false rumours”, he adds.

He is still in touch with Seale, now 88, who became like a mentor to him: “I’ll call him on the phone once in a while and we’ll chat for an hour.” Ultimately, Shames hopes that the London show – his first solo exhibit in the UK – will lead to greater interest in his Black Panther photographs in the US. “Maybe Trump will exhibit them at the White House,” he jokes. “I think I should write to him.”

Born in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Shames credits his parents with raising him to have liberal values: his father, a Harvard-educated lawyer who “grew up poor in Milwaukee”, had even joined him on the anti-war march where he met Seale. Looking back, he thinks he was drawn to the Black Panther movement because, unlike the Black nationalism movement, the Panthers welcomed white people from different backgrounds (as well as people of Hispanic, Native American and Asian heritage).

“I’m Jewish, and I read every book on the Holocaust when I was younger,” says Shames, who now lives in New York. “Bobby often said: ‘Look, we’re fighting racism, so we’re not going to be racist.’ The Panthers weren’t saying Black people are superior and white people are devils. They were basically saying: ‘We’re all humans and every human is equal.’”

By the end of the 1960s, the Black Panthers had founded a multicultural “rainbow coalition” of socialist community groups which were fighting against poverty, racism and police brutality. “They were very cosmopolitan, and that was something I liked about them. In the 1960s, music and culture and politics was all mixed up in a way that it hasn’t been since, because it was really breaking away from segregation.”

In Shames’s opinion, the Black Panther movement laid down a path for gay rights, the women’s movement and disability activists to follow. “A lot of these movements were inspired to stop thinking of themselves as victims and to actually start saying: ‘We need this because we’re equal.’”

Across politics and popular culture, the impact of the Black Panthers went “way beyond Black civil rights”, Shames says – and that is why it is so important to remember today. “Look at what’s happening in the US. Look at the rise of rightwing, proto-Nazi parties all over the world. It’s very scary, and I think it’s important for people to see that in the 1960s we had leaders and we found solutions.”

Black Panthers & Revolution: The Art of Stephen Shames will run from 28 May to 6 July at the Amar Gallery in Fitzrovia, London

Photographs by Stephen Shames, courtesy of the Amar Gallery