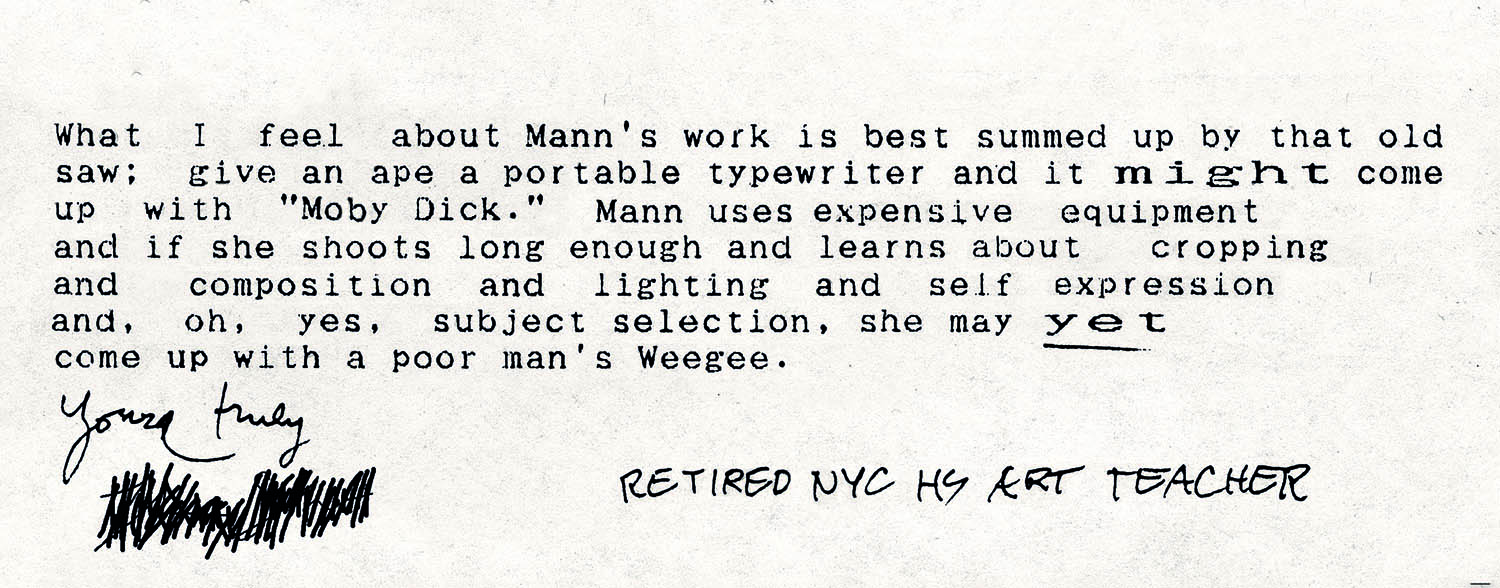

This retired art teacher busted me, and my simian process, in his letter to the New York Times (below) way back in 1992. His self-reported experience with photography, beginning in college in the 1940s and later as a photo teacher at a local boys’ club, sharpened his eye for fakery in all forms.

But he was wrong about the expensive equipment and dead wrong about Moby-Dick. No monkeys, no matter how dexterous or numerous, could ever write Moby-Dick, one of my favourite books. They’d be lucky just to get the title. And, likewise, sometimes no amount of trying, no amount of good old stick-to-itiveness, will get you a good picture. It pains me to say this and it didn’t happen all that often to me, but sometimes, in fact, you just have to give up.

Like this damn dead duck I was obsessed with.

My friends John and Leslie raised fowl of various kinds, slaughtering and freezing them. This was before I had chickens myself and I was still charmed by their deranged chaos. I knew that a chicken dustup was virtually guaranteed if I brought feed and tossed it into the background of a picture with a kid in it. Bound to get something interesting. For one whole autumn, I’d pick the kids up after school several days a week and go out to my friends’ farm, where I’d set up the camera among the feathers, manure and dusty scratchings, hoping I could get something good without anybody getting raked by a rooster’s spur.

One day when we arrived, Leslie had grabbed up a flapping, honking, dander-spewing duck and was holding it upside down by the yellow feet. We watched in fascination as she fed the head and long neck down an aluminium funnel-like contraption that was affixed to the fence post. As the duck was squeezed into the funnel, the flapping diminished and pretty soon out of the lower cone-hole emerged the beak and head, then the neck of the still-squawking bird. One quick flick of Leslie’s knife at the touchingly vulnerable throat and the bird was silenced, blood pouring into the bucket below.

By that time, of course, never one to miss the photographic opportunities at an execution, I had run back to the car, grabbed my camera and had it set up at the ready. The kids were backing away, staring in horror and fascination as the yellow legs began to droop. Brightly, I inquired: “Who wants to be in this picture?” and three pale faces swivelled to me in disbelief. It ended up being Jessie, my brave girl, with my son Emmett willing to play his part a safe distance away.

For whatever reason, I didn’t think the original picture (above) was any good – although almost 40 years later I rather like it – so I asked Leslie if the next time she was slaughtering she would be willing to set aside a duck for me so I could try to reshoot the picture. She obliged, putting an exsanguinated carcass in the freezer so that I could come and get it any time for a repeat picture.

Or, as it happened, dozens of repeat pictures. I tried taking that damn duck picture so often that its wing feathers snapped and the jagged, hollow quills threatened to stab Leslie every time she reached into the freezer that winter.

Even the indefatigable Jessie flagged.

A few times I had to call in the understudies. Of course, I had to bring my own blood each time, having found the Karo syrup I tried the first few times unconvincing. I once hastily stuffed the syrup back into my camera bag loosely capped after dripping it on to the bucket – with a predictably bad result. At least it wasn’t the jar of blood.

As winter turned to spring, and we were still ramming the rock-hard carcass into the cone, and likewise ramming this dumb idea into the dead end where it clearly was headed, Jessie put her foot down and asked for a reward: a red taffeta ball gown she had seen at the Stonewall Jackson hospital thrift shop the week before. The afternoon we were to take our last trip to the cone, I dashed to the thrift shop and grabbed it, standing across the card table from the Pink Ladies’ volunteer as she tucked the handful of dollars into a metal box and expertly rolled up the red dress in a spread of newspaper.

No matter how briefly I was in that shop, I always seemed to run into one of our local nutters – you know how a small town loves its characters – most memorably once seen lugging two brown paper grocery bags full of cash from his sale of a Cy Twombly painting he had kept behind his sofa for 40 years. And sure enough, he swaggered down the ramp, yelling his usual question: “Who’s died? Anybody in my size?”

The first time I saw Jessie holding a candy cigarette, looking like something out of a 1920s Hollywood still, I knew there was a story

The first time I saw Jessie holding a candy cigarette, looking like something out of a 1920s Hollywood still, I knew there was a story

This man had been a scourge of my young life, having fallen in love with my father, who was his medical doctor, and becoming enraged by the rebuff he received. It was doubtless a kind and courtly one, as befitted my father’s nonjudgmental personality, but a rebuff all the same. He then sued my father, saying he had fallen off the swivel stool used for examinations, and when that didn’t work, he burst into the office and threatened my father with a gun.

My Texan father was no stranger to guns and began concealing them in both the house and the office, and installed a warning buzzer beneath his secretary’s desk at the office. I have a clear memory of his little derringer once lying casually beside him as we ate dinner.

But even with the gift of the red gown, this duck picture couldn’t be saved. Not that it was Jessie’s fault, mind you; it was 100% my fault. The more times I tried, the worse it got. In the end, the first picture was probably the best, just not good enough. Mila Sevo, my archival studies summer intern (who as I write is struggling through the boxes of negatives) reported to me last week that so far, she has found about 58 negatives of dead-duck pictures.

I suppose that knowing when to stop is just as important as knowing when to push through – although perhaps it’s only the difference between the unvanquished, determined monkey typist who happens to be stone-blind and the equally tenacious seeing monkey who thinks he may discern a hidden pattern and attacks the keys in a frenzied search for it.

So often I would feel there was a great picture just there, teasingly close, with skittish, floating elements – the insolent cast of an eye, the pert lip-curl – that simply needed to lock into their divinely determined slot.

The first time I saw Jessie holding a candy cigarette (above), looking like something out of a 1920s Hollywood movie still, I knew there was a story there and I began corralling the supporting elements for a picture that I built as carefully as a mason knits together a stone wall. I returned to it over and over again. Many Boxes of candy cigarettes.

Many annoyed extras: Jessie’s friend Rachel, my mother, Emmett and especially my daughter Virginia.

And then, the right keys were struck, at the miraculous right time:

M-O-B-Y-D-I-C-K.

SMIF_063_NEW_2, 10/3/13, 10:19 AM, 16G, 5584x6659 (111+1319), 75%, Custom, 1/50 s, R45.6, G29.5, B53.1

Extracted from Art Work: On the Creative Life by Sally Mann. Published by Particular Books on 18 September at £25. Order a copy at observershop.co.uk for £22.50. Delivery charges may apply

Photographs courtesy of Sally Mann

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy