One slow day in the life

In Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Holly Golightly wryly observes: “Clocks are slow on Sundays.” This sentiment certainly applies to Olivier Schrauwen’s masterful graphic novel Sunday, where a single day unfolds in meticulous and often excruciating detail over nearly 500 pages, despite nothing particularly significant occurring. Riffing on a tradition of 24-hour narratives stretching back to Ulysses and Mrs Dalloway, via Heinrich Böll, Don DeLillo and Rachel Cusk, Schrauwen has crafted an unflinching, painfully funny portrait of a wasted day and an oddly moving meditation on the elusive nature of language, memory and perception.

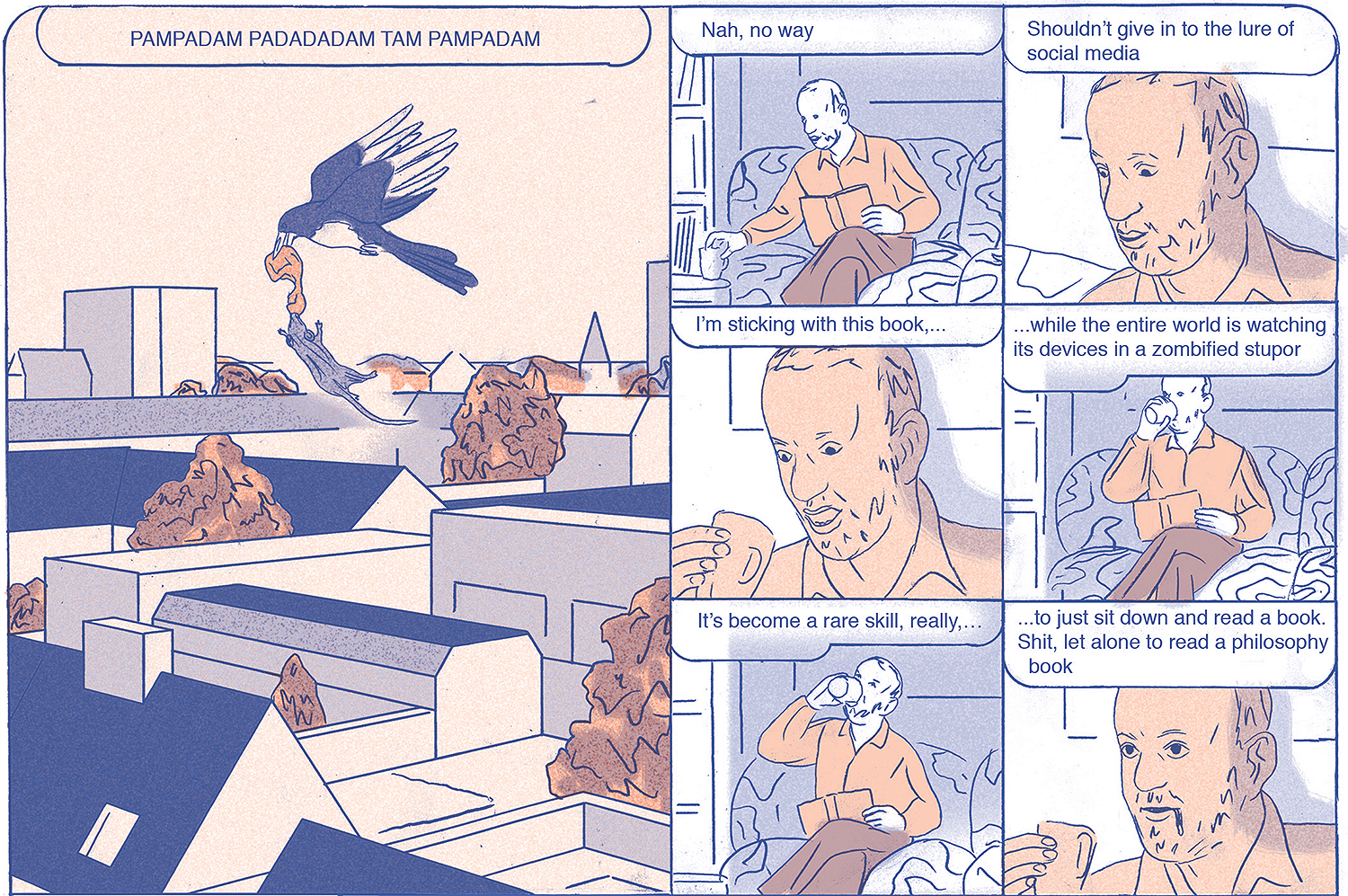

The book’s central character, Thibault, is a thirtysomething font designer loosely based on the author’s own cousin and, as we quickly learn, a bit of a flake. Feckless and self-absorbed, he is a master of procrastination, all but oblivious to the responsibilities of his personal and professional lives. He routinely blows deadlines, ignores emails from clients, avoids friends and neighbours, and blithely fantasises about an ex-girlfriend while waiting for his current partner to return from a trip. And yet here we are, trapped inside his head from the moment he wakes to the stroke of midnight on the day before his birthday. During this time, he will bathe, masturbate, fail repeatedly to get past the first sentence of a philosophy book, cook an inedible meal, get wasted on booze and marijuana, accidentally burn off an eyebrow and pass out.

What might have seemed laughable at first suddenly becomes almost heroic

What might have seemed laughable at first suddenly becomes almost heroic

Accompanying this (non) action is Thibault’s rambling internal monologue, which shifts in register between the banal and the nonsensical, punctuated by bursts of the irksome psychic fuzz which can so easily infect our brains when our guard is down. Absurd reveries, exasperating earworms, unpleasant memories and passages of utter gibberish invade his thoughts over the course of the day, repeating over and over until the steady accretion of details merges into a hypnotic stream-of-consciousness symphony.

Schrauwen has spent more than two decades mastering the language of comics, and the richness he brings to Sunday’s visual design and construction is deeply impressive. Carefully managed shifts in colour and line suggest changes in time, place and mode of perception, switching effortlessly between reality and fantasy, dream and memory. As Thibault gets progressively more plastered, the rigid grid pattern of the early chapters gives way to elaborate, serpentine collages of twisting panels, blurred overlapping images and distorted text. Meanwhile, the colour palette of the entire book changes over the course of the day, from the pale pink and hazy blue of early morning light to deep shades of purple evoking the encroaching night. By the final chapter, approaching midnight, pages are consumed by the silent black and blue-grey of the sleeping city.

Schrauwen is also adept at wringing moments of awkward humour from Thibault’s boorish behaviour and banal musings, saving Sunday from becoming a simple study of urban alienation. At its heart, it is a meditation on language and the difficulties of finding meaning in the chaos of the modern world, both literally and metaphorically. Thibault spends much of his time analysing the random signs and symbols he sees around him, but his innate lack of insight dooms his efforts to failure. At one point he traces images from his ex-girlfriend’s Instagram account, turning them into silhouettes from which he tries to extrapolate letters of the alphabet, vainly hoping they will contain some kind of hidden message just for him. They don’t. Later, he will analyse a single freeze-frame from The Da Vinci Code, a film based on what many consider to be one of the worst books ever written. It’s hardly surprising that meaning eludes him at every step.

Only towards the end do we learn in passing that he suffers from dysgraphia, a condition that impedes writing ability and the formation of letters. This moment barely registers, but with it everything falls into place. This man, who designs letters and symbols for a living, is utterly out of his depth and grasping at straws, but still he keeps searching. Somehow, we have to marvel at his persistence, and what might have seemed laughable at first suddenly becomes almost heroic.

We are never left with the sense that Thibault is irredeemable. Throughout the book, we catch glimpses of his friends and acquaintances, who clearly care for him despite his flaws. As they prepare to throw a surprise birthday party for him, their own stories create a rhythmic counterpoint to his internal monologue. These moments of synchronicity suggest that there might be some deeper meaning out there after all. As they gradually come together, ready to surprise him at midnight, the symphony of their lives reaches its crescendo. However, the climactic moment is ultimately denied to us; it belongs to another day.

All We Imagine As Light

As the home of India’s film industry, Mumbai ought to be the perfect setting for a city film. At first glance, All We Imagine As Light takes a stab at it, beginning by looking out on to the city’s streets from a passing vehicle. With a nod to the opening of François Truffaut’s Les 400 Coups, director Payal Kapadia layers this gaze of bustling evening crowds with voiceovers from those same people. In their own words and languages, these nameless, faceless voices explain their coming to the city, and anticipate their going.

It is these two movements, towards and away from urbanity, that characterise Kapadia’s Cannes Grand Prix-winning film. Our two main characters, nurses Prabha (Kani Kusruti) and Anu (Divya Prabha), are roommates sharing a poky flat. They have a bond approaching sisterhood, tethered by their places of work and residence, as well as their shared background and language as Malayalam-speakers from the state of Kerala.

As Anu, a new arrival to the city brimming with hopes of romance, Prabha shines with wide-eyed aspiration, proudly abuzz with the not-so-secret knowledge of her secret lover. Meanwhile, Kusruti embodies a Prabha who is in the thick of her urban life, attuned to the rhythms of the city, and appropriately regular, robotic even, in her ways. As friends, the two make an unlikely pair. We watch their everyday lives unfold: the glassy-eyed Prabha takes crowded local trains (an iconic symbol of Mumbai) to and from the clinic, while Anu takes the spanking new metro to make clandestine visits to her Muslim lover, Shiaz (Hridhu Haroon).

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

If the city can be a character in a film, here it is the villain

If the city can be a character in a film, here it is the villain

Soon the monsoon sets in, and Prabha’s monotony is broken by sudden downpours and the equally sudden arrival of a rice cooker in the post. Here, Kusruti’s blank stares and surface smiles at patients give way to muted excitement. Is the package a mistake or a gift? Prabha decides the latter, interpreting it as a token from her estranged husband, secretly embracing this commodity as a stand-in for love, echoing a moment in Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love in which Maggie Cheung’s character flaunts a rice cooker gifted from her distant husband.

Anu and Prabha’s dyad is complemented by the introduction of Parvaty (Chhaya Kadam), an ageing orderly at the clinic who faces eviction from her tenement as it is razed to make way for luxury apartments. She lacks the papers for her home, but not grit. Her fight for a place in the city is revolutionary, but Kapadia makes no pretence at a fantasyland in which Parvaty might avoid the inevitable. Parvaty’s is the fate of many of India’s urban working class, who are so often referred to as “migrant labourers”, as if to deny them the very potential of a permanent place in the city.

Both on and off screen, city-spaces are thought of as diverse and dynamic tapestries. But Mumbai is acutely partitioned, and it is tacitly acknowledged that certain people cannot live in certain places. Kapadia – who began as a documentarist – makes no attempt to veil this reality, instead foregrounding Anu and Shiaz’s interreligious relationship against it. As a result, their affair, like so many of the private adventures that the film’s characters undertake, feels doomed from the start. But the couple persist, developing plans involving burqas and secluded caves to find for themselves the city’s scarcest commodity: a private space.

Kapadia’s frankness in presenting this subplot came to the film’s commercial detriment, potentially contributing to it being overlooked for India’s Oscars entry and its subsequent scuppered domestic release. Exuding the persistence of her characters, Kapadia herself eventually stepped in to organise Indian screenings over X (formerly Twitter).

The film has been characterised by some critics as a love letter to Mumbai, the city collating this pan-Indian ensemble of voices. But Mumbai fetches up and spits out the film’s characters, and Kapadia herself has repeatedly expressed this in interviews. Paradoxically, it is only when our trio of spiritual sisters leave the city to visit Parvaty’s ancestral village that they get anywhere near their otherwise unattainable dreams.

All We Imagine As Light is an “anti-city” city film, relishing in the characteristic visuals and sounds of the genre with its upwards shots and tinkling overtures, while doing its utmost to undermine romanticism at every turn. If the city can be a character in a film, here it is the villain. The dreamscape of Mumbai is presented through the commodities of a rapidly modernising world, trips to the cinema, and jumbo-sized billboards, all of which cast a shine on the faces of our characters whenever they glance upon them. But this glistening “Mumbai Dream” is really a glare, a Sisyphean endpoint that tempts, but remains just out of reach.

Making a rukus!

Ivor Cummings, born to a white English mother and a Sierra Leonean father, played a pivotal role in supporting Black migrants in Britain during and after the second world war, yet his contributions are often overlooked. His work is particularly significant in the context of Black LGBTQ+ history as he was openly gay at a time when homosexuality was illegal. As a liaison in the Colonial Office, he helped workers and servicemen, ensuring they found housing and employment. Academic Nicholas Boston aptly called him the “gay father of the Windrush generation”. Cummings’s story, like so many others, risks being forgotten due to the historical neglect of Black queer figures.

This urgent need to preserve oral histories, particularly those of Black LGBTQ+ individuals in the UK, is precisely what the rukus! archive – Europe’s largest collection of Black British LGBTQ+ culture and history, housed at the London Archives – aims to address. Founded by self-proclaimed “Unruly Queer” Topher Campbell and photographer Ajamu X, Making a rukus! is undertaking what Jason Okundaye calls “emergency work” to document and protect the stories of the first generation of openly gay Black men.

Making a rukus! is their largest archive exhibition yet, a carnivalesque celebration of Black queer life – part history lesson, part defiance, and an invitation to become immersed in a past that won’t be erased.

The frenetic energy of the piece reflects not just a singular experience but also a shared reality for many Black gay men at the time

The frenetic energy of the piece reflects not just a singular experience but also a shared reality for many Black gay men at the time

The first installation sets the tone: a screen displays The Homecoming: A Short Film About Ajamu, one of Campbell’s most significant works. It follows photographer Ajamu X navigating 1990s London, encountering homophobia as he attempts to make his way back up north. The frenetic energy of the piece reflects not just a singular experience but also a shared reality for many Black gay men at the time. Other artefacts from the early days – press clippings, photography and personal mementos – showcase the grassroots kitchen-table energy that built this project.

The second space deepens the exploration of community-building, displaying meeting minutes, flyers, clothing and protest materials that document the solidarity and resistance of Black LGBTQ+ people in Britain. Posters from past events, including the work of poet Dorothea Smartt and playwright Mojisola Adebayo, highlight the networks of creativity and activism that endured despite a hostile social climate. This space feels like an unfolding conversation between past and present, a tangible reminder that activism is never just about survival but also about joy, expression and cultural production.

The third installation moves away from documentation and into immersion. A mirrored dancefloor, part of an installation by artist Evan Ifekoya (A Score, A Groove, A Phantom, A rukus!), transforms the space into a club-like environment. Voices narrate their first club experiences, weaving collective memories of dancefloors as places of refuge, resistance and self-discovery. Black queer club culture has always been more than nightlife; it has been a sanctuary, a political act and a declaration of existence. The echoes of laughter, music and stories in this space remind visitors that joy is its own form of protest.

The final exhibit – a living room with armchairs and a television – plays footage from the 1987 national Black Gay Men’s conference. The setting is a deliberate nod to Michael McMillan’s The West Indian Front Room, repurposed here to highlight the rampant homophobia in similar living rooms, yet Black gay men were carving out spaces for themselves regardless. The choice to end the exhibition in a domestic space underscores how these stories have always existed – whether acknowledged or not – within homes, families and everyday life.

Before visiting, I read Okundaye’s Revolutionary Acts: Love & Brotherhood in Black Gay Britain. I was struck by how many of the wonderful characters he interviewed appeared in the exhibition, creating a rich interplay between written and visual history. There is something profoundly moving about how Making a rukus! asks us to pay attention to seemingly incongruous artefacts. Newspaper clippings sit next to rave flyers, and protest banners are displayed alongside intimate photographs. James Baldwin once wrote that it is a reminder that “our stories are the only thing we have that can give us a sense of the world’s immensity”.

This exhibition doesn’t attempt to create a polished, definitive history of Black LGBTQ+ life in Britain. Instead, it acknowledges the messiness of memory and the difficulty of preservation while making a powerful case for why this work is essential. The artefacts we need to tell these stories are all still out there – tucked away in attics, in black bin bags, in garages – waiting to be recognised. This exhibition is an urgent reminder that documenting history is never finished and that every saved flyer, every recorded voice and every reclaimed memory is an act of survival in and of itself.