Parsifal

Il barbiere di Siviglia

Glyndebourne, Lewes, East Sussex; until 24 June/3 July

Barking in an insistent monotone – think of a car alarm – a lone booer felt the need to make their mark amid the noisy rapture at the end of Wagner’s Parsifal: its first staging in Glyndebourne festival’s 91-year history, and an opera its founder, John Christie, always wanted to see performed in his private theatre. The reason to mention this trivial discourtesy is to try to understand the response this final “sacred drama” by Wagner provokes, and to acknowledge the visceral ownership audiences feel towards the sprawling epic of sex, death, redemption. A shoddy performance is a different matter, not relevant here. Glyndebourne’s handsome production, which together with a revival of Rossini’s Il barbiere di Siviglia launched the 2025 season, was conducted with intensity and perception by the company’s music director, Robin Ticciati. Cast, chorus and resident London Philharmonic Orchestra, glowing and nuanced, performed with engrossing authority. You could recommend it for the brilliance of the solo cor anglais playing alone.

An emphasis on energy and momentum meant everyone at times scrambled to keep up, which only added to the comedy

An emphasis on energy and momentum meant everyone at times scrambled to keep up, which only added to the comedy

The point of contention, as so often with Parsifal, is the staging. Wagner provided his own fussily detailed instructions: castle of the grail, mountainous terrain, forest “shady and solemn but not gloomy”. The composer’s grandson Wieland Wagner scotched all that with his minimalist but stylish abstractions of 1951 – little other than a circle on an empty stage. A more recent turning point was Stefan Herheim’s 2008 staging for Bayreuth, the action set in the composer’s own home, Villa Wahnfried. Here was a stark portrait of German history complete with antisemitism, swastikas and Marlene Dietrich parallels.

Between these extremes, other directors have found compromises for a work that has no compromise. Wagner completed it – after 17 years’ effort – shortly before his death in 1883, a summation of his life’s work. Parsifal is not a sequel to his other operas but a gathering up of all that preoccupied Wagner, of the careless dreams of youth, the dissolute consequence of ambition, the regret of generations, wasted by ego and desire. How to put that on stage in a drama where, aside from a young man killing a swan and an oldish man lying on a bed with a sex-related wound, little happens.

The Glyndebourne team, led by Dutch director Jetske Mijnssen, designer Ben Baur and lighting designer Fabrice Kebour, has downplayed allegory and treated the piece as a Victorian family drama, with echoes of Ibsen and Chekhov. The ancient king Titurel (John Tomlinson, working majestically through all the bass roles in the Wagner canon), fidgets and worries as his dynasty disintegrates and his ailing son Amfortas (an ever eloquent Audun Iversen) writhes, longing to die. Parsifal (Daniel Johansson), the holy fool, wearing an awkward long-haired wig, has the look of a Russian student who finds himself beaten up by thuggish knights.

The role is smaller than the title of the opera suggests, and Johansson was rather eclipsed by all the tableau backstories being enacted at the rear of the stage. Trying to explain what happened before curtain up in any Wagner opera is a reasonable idea, but you needed a fair grasp already to understand who was who and what was going on. That said, all was incisively thought through, with Klingsor here portrayed as Amfortas’s estranged brother seeking prodigal forgiveness. The lustful sorcerer, enemy of the grail knights, was superbly sung by Ryan Speedo Green.

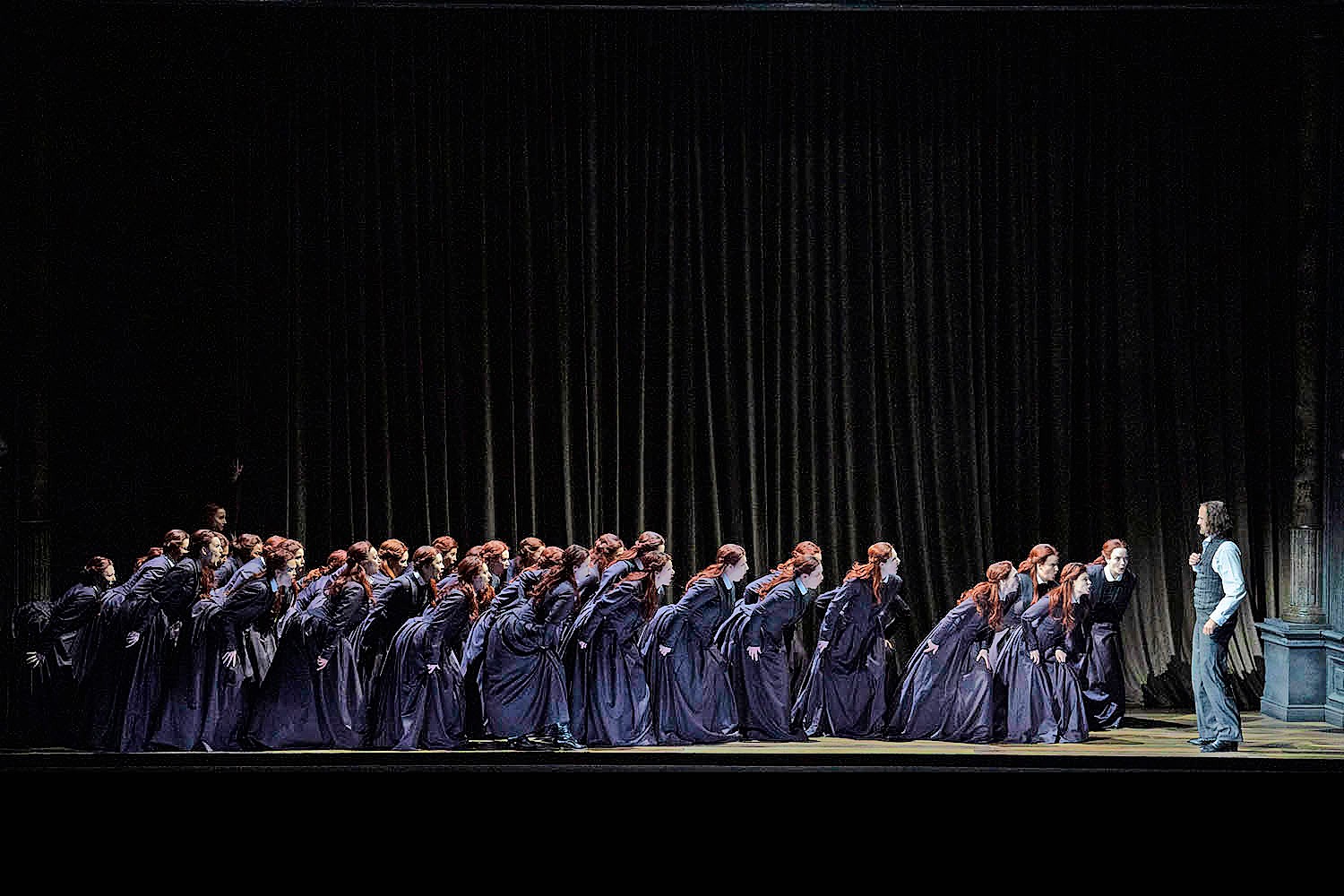

The stark interiors of the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi, now almost a cliche in opera designs but always effective, are a visual touchstone. Shafts of light brighten a dark drawing room through tall shuttered windows. This salon doubles as the hall of the grail, a place of flickering candles and many men in clerical surplices, like a gaggle of lay clerks or vicars. (A German speaker, overheard at the interval, complained that the Act 1 grail office – equivalent to a celebration of the mass – looked “too Protestant”.) A pre-Raphaelite medievalism is sewn into the design: Kundry and her identical Flower Maidens, red-haired and sombrely gowned, are doubles of Tennyson’s Mariana as depicted (in 1851) by Millais: “I am aweary, aweary, O God that I were dead.” Delphiniums, beloved of Victorians but toxic, add the only splashes of colour.

In this spaciously paced account, in which Ticciati confidently allowed silence to be as vital as sound, two performances stood out. Kristina Stanek as the multifaceted Kundry, at once servant, sexual predator, intercessor – Mary Magdalene is never far away – sang with glorious light, shade and power. Above all, John Relyea in the huge role of Gurnemanz, narrator and conscience of the entire proceedings, gave an unforgettable account, his despair heartfelt. With a portrayal of this splendour, sharing the stage with Tomlinson, who has triumphed as Gurnemanz in the past, Glyndebourne has honoured John Christie’s original vision. It is, without question, a home for Wagner.

Related articles:

The intoxicating pleasures of Il barbiere di Siviglia the previous night – the festival’s opener in a cleverly refreshed revival of Annabel Arden’s 2016 staging – were a perfect aperitif. Everyone participating caught the fizz and precision of Rossini’s music, as well as his eccentric humour. Conductor Rory Macdonald put an emphasis on energy and momentum. Cecilia Molinari’s deliciously sharp-tongued Rosina, Fabio Capitanucci’s rumpled and appealing Dr Bartolo, Jonah Hoskins’s agile Count Almaviva and Germán Olvera’s wry and tumbling Figaro all at times scrambled to keep up, which only added to the comedy (well-drilled chorus and actors helping too). Elaborate vocal ornamentation is central to this opera. The following night, Viennese countertenor JJ won Eurovision. Worth noting that he first knew he had vocal talent when he tried singing Mozart’s Queen of the Night aria. Great coloratura always steals the show.

Photographs by Richard Hubert Smith and Tristram Kenton

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy