What will the UK look like in 2070? The population will rise by seven million, hitting 76 million, the UN predicts. But it could shrink to 65 million or swell to 88 million, depending on what happens with birth rates and immigration. Temperatures may rise 1C, if countries stick to their Paris Agreement promises, but could be up 2.5C if they do not. Computer chips will be 6m times more powerful, but only if Moore’s Law holds. On a 45-year view, things are uncertain.

Except when it comes to UK debt. The British government’s IOUs currently total £3tn, a little over 100% of GDP. They include bonds that mature – that is, must be paid back – in 2071 and 2073. Forget about death and taxes: the only thing certain about the future is debt.

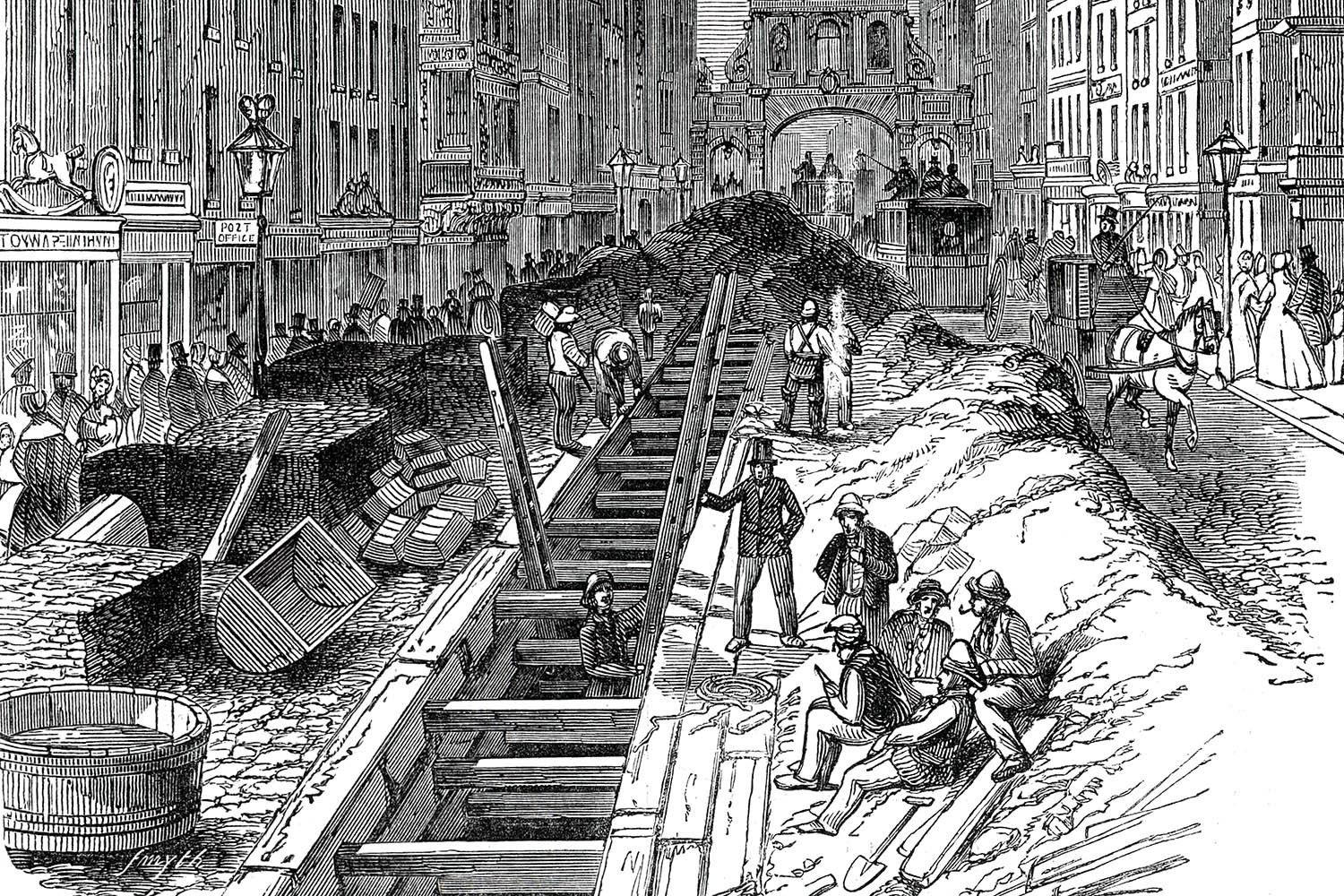

Beware the economist that tells you debt is bad. Bonds allow nations (or companies) to transport funds from far into the future – 2073 in Britain’s case – and make that cash available today. Bonds have supported new nations – America borrowed heavily from France in the 1700s. The “Great Stink” of 1858 showed London needed huge new sewerage investment – it was financed by bonds.

More recently, the UK’s “Green Gilts” raised £70bn for environmental projects. New countries, clean cities, sustainable futures – debt can signal strength.

But you can have too much of a good thing. On a 45-year view Britain’s debt will be 270% of GDP, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) warned this week. One cause is ageing. Britain will have millions more pensioners and the “triple-lock” means pension payments ratchet up mechanically, rising by the higher inflation, wages, or 2.5%. Unable to finance spending via taxation, the debt will soar, the OBR shows.

The temptation is to point the finger at Westminster: HM Treasury needs better ideas on growth; the fiscal rules need to be changed; the OBR needs to sharpen up its forecasts. These familiar arguments are sharper when you look across the channel: France has more debt (116% of GDP) and a higher deficit, yet pays less to borrow.

Step back, though, and see this is a global problem. All advanced nations have large debt piles: of the G7 nations, only Germany’s are below 100% of GDP. The long-term pattern of interest rates – down and down, then recently up – look the same.

No advanced nation has been able to find savings. Japan has been attempting to lower its deficit since the 1990s: campaigns to trim farm subsidies and pension payments failed. America’s recent cost-cutting drive (the Department for Government Efficiency) found less than 2% of the $2tn savings it promised. In France, raising the pension age to just 64 led to a million protesters in the streets. A wider perspective does not excuse Britain from efforts to control debt – it shows how hard the path will be.

As well as helping to build the economy of tomorrow, bond markets protect us today by acting as a form of insurance. We don’t know what the crises will be on the road to 2070, but on a 45-year view we can be sure that many will come. Some will require a sudden issuance of debt. By stretching bond markets to the limit, advanced nations are eroding this buffer and making the future more fragile.

Richard Davies is director of the UK’s Economics Observatory

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy