Allwyn has been lucky since it became the National Lottery operator 18 months ago. The EuroMillions lottery numbers have delivered four jackpot rollovers, an unusually high number. Rollovers drive ticket sales and Allwyn International listed “favourable jackpot cycles” in EuroMillions as one of the primary reasons why its revenues rose by 14% year-on-year in its September accounts.

Last week, Allwyn rode that luck by announcing a merger with Opap, a Greek gaming firm, to become the second largest gambling company globally with a valuation of £13.8bn.

For Karel Komárek, the company’s media-shy Czech founder, the merger is a crowning success. When Sazka, the Czech lottery, went bankrupt in 2012, Komárek swooped on the lottery rights, picking them up for less than £150m, and used Sazka to assemble a European gaming empire that dwarfs his original oil and gas fortune.

The Opap acquisition – Komárek’s investment firm KKCG will control 85% of voting rights of the new entity – means Allwyn will finally have a public listing, on the Athens Stock Exchange. His aim is for a secondary listing in London or New York to access equity for further expansion, particularly in the US, and supplant Flutter as the world’s largest gambling group.

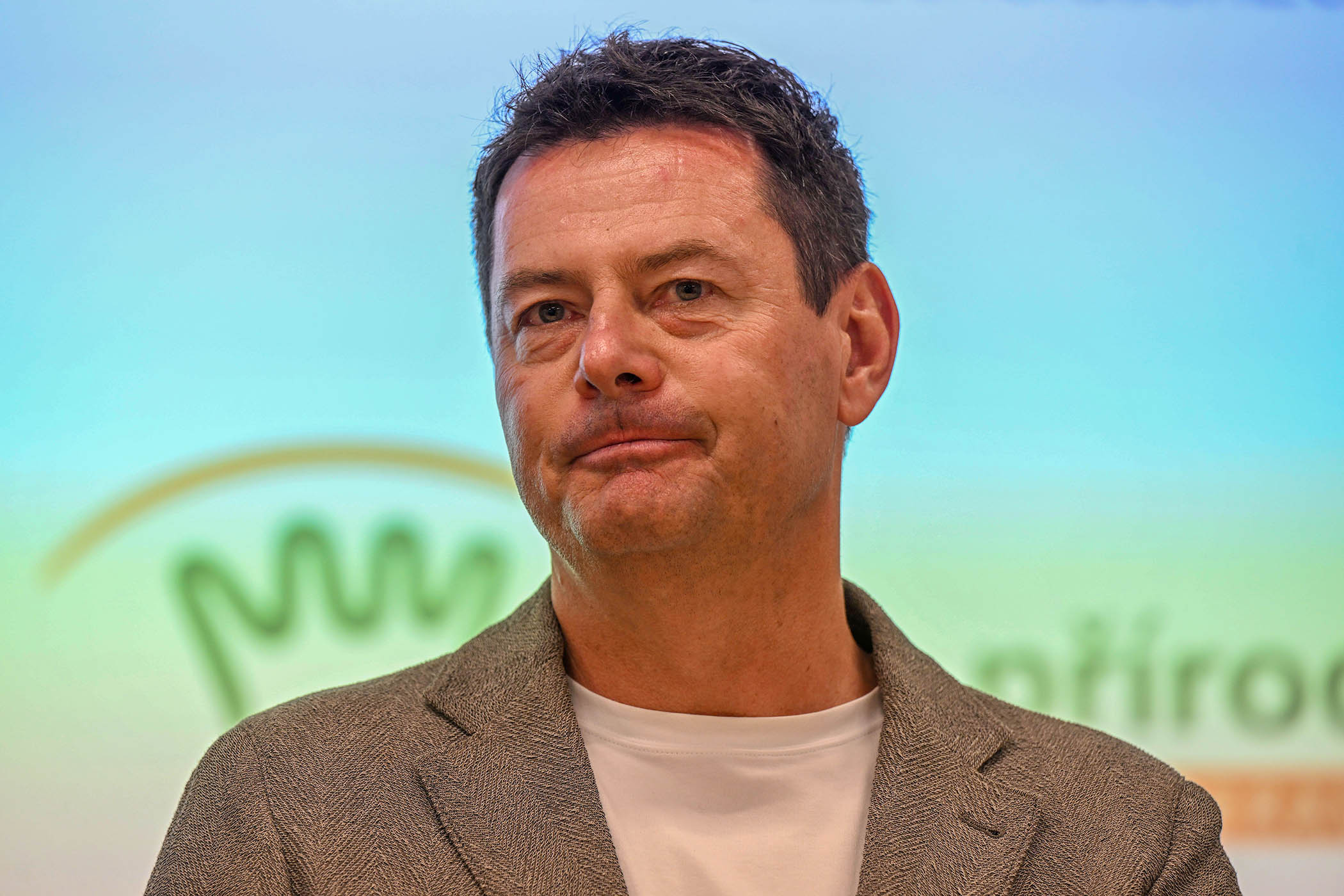

Karel Komárek

How long the 56-year-old billionaire’s luck lasts is a different matter. Allwyn’s UK arm is embroiled in a seven-week court battle between Richard Desmond’s Northern & Shell publishers and the Gambling Commission over the way the regulator granted the National Lottery licence.

Desmond wants £1.3bn in damages, claiming the bidding process for the 10-year licence was flawed and Allwyn has been allowed to break commitments that were in its bid contract. The media mogul also claims that Allwyn was an unsuitable operator because at the time of the bid KKCG was linked with Russian-owned businesses, including a joint venture with Gazprom.

Another factor in the case is the role of Rothschild, the financial adviser, which had previously advised Allwyn before being appointed by the Gambling Commission to advise on the bidding process. Allwyn’s bid brought in luminaries including Sir Keith Mills, the London 2012 Olympics organiser, and an ally of former prime minister Boris Johnson, and Justin King, the former Sainsbury’s boss. Allwyn said in court documents that the Gambling Commission's approach was "plainly lawful".

Before Camelot lost the licence after 28 years in 2022, its executives believed they were in pole position. But a key element of the bid was changed in the weeks before the decision – the “solution risk factor”, which was intended to balance overblown promises by the bidders –was effectively abandoned. Camelot sued the commission, but the action was dropped after Allwyn bought its former rival.

Allwyn’s bid included an ambitious pledge to double money for good causes to £38bn over 10 years. Its first year total was £1.8bn, less than half the pledge and in line with Camelot’s performance.

However, the National Lottery Community Fund, which hands out 40% of money to good causes, said it was so confident in Allwyn’s plans that it had made long-term commitments to intermediary funding partnerships, including £20m for Propel and £30m for The Phoenix Way. Even so, if Desmond wins, Allwyn’s plans would be blown out of the water because compensation would probably be drawn from the good causes funds.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Not every Allwyn partner has been happy. A key part of its plan was to introduce new gaming terminals that retailers use to sell lottery tickets. Yet a summer switchover drew complaints that the new terminals did not work or were harder to use. Some even posted pictures on social media of ripped-out terminals. Jason Byrne, who runs Kingswear post office in Devon, said the switchover in summer had been a “complete shambles from day one”.

Allwyn pointed out that it had 43,500 retail partners and had worked hard to resolve issues. It also said that its promotions had helped attract players. An Allwyn spokesperson said: “We’re pleased with our strong performance in the first six months of this year. The EuroMillions rolls have driven player excitement, and therefore sales and returns to good causes, especially as EuroMillons gives a bigger proportion to good causes than other games.

“These big jackpots, combined with new marketing initiatives, also bring in new players and drive interest in other games. We are confident we will double the amount raised for good causes from £30m a week to £60m a week by the end of the current licence.”

• This article has been amended post-publication

Photograph by Ian Gavan/Getty Images for The National Lottery