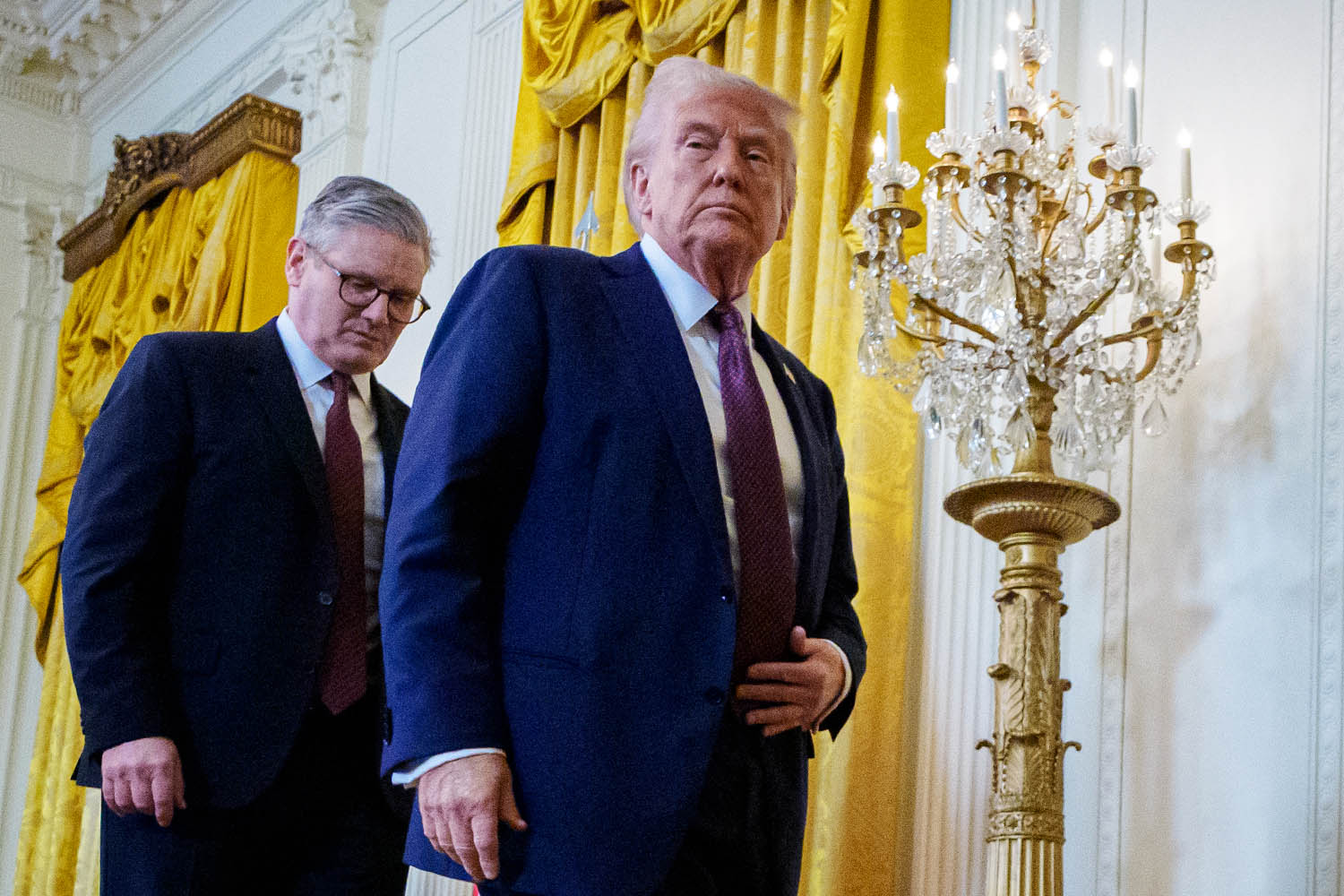

Reactions to Keir Starmer’s modest “reset” of UK-EU relations last week in the rightwing press took hyperbole into new realms of the absurd. It was a “surrender” in which we could “kiss goodbye to Brexit”.

You would never guess that only the edges had been taken off Boris Johnson’s very hard Brexit – and that for all those welcome advances, in its essentials the UK cannot get beyond being, in EU terms, a “third” country, alone.

Britain will remain decisively outside both the EU customs union and single market. The Brexit right has succeeded in locking our geo-economic position firmly within the ambit of the US, the dollar and its mighty capital markets to which Britain’s are umbilically linked. Thus, for example, if yields on US bonds rise, lifting the cost of government borrowing, ours ineluctably follow.

Last week dramatised how uncomfortable this standing between two giants can be as Trump launched “one big beautiful bill”, one of the most economically and financially toxic measures in the US’s recent economic history, while the next day threatening 50% tariffs on all EU goods imports because he no longer wanted a deal with one of the US’s biggest trading partners – or so he said. His budget had already prompted US 30-year bond yields to climb above 5%, but simultaneously triggered a mirror-image rise in UK 30-year debt yields to more than 5.5%, a near all-time high. Share prices were sliding too. Yet confronted with this mayhem, to argue that the UK should try to build as close an association with the EU as it can – central to global free trade and financially predictable – is to invite a frenzy of ridicule.

Last Thursday, the House of Representatives passed by a single vote Donald Trump’s fantastical budget. Anticipating this would happen, the credit ratings agency Moody’s had a few days earlier joined the other major agencies, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch, in lowering the triple-A credit rating of US government debt – a rating it had accorded the US for more than a century. The country’s debt was suddenly riskier, warning lenders to want higher interest rates for their loans. With the US’s growing debt mountain lifting prospective annual debt servicing costs to exceed defence spending and a gridlocked Congress unable to do anything but either spend big or lower taxes big, the prospect of a Trump budget, riddled with giveaways and extravagant tax cuts for the wealthy, had sealed the deal. Moody’s called time.

US treasury secretary Scott Bessent shrugged off the bond market reaction. The US’s vast budget deficit (proportionally twice our own), inherited from Biden, might grow even higher – but unlike Biden’s, he claimed, the thrust was now growth-inducing tax cuts that would magically pay for themselves, one of the most contentious theorems in economics. Holders of the US’s $36 trillion public debt mountain thought differently. The obvious risk is that the “big beautiful bill” interacts with Trump’s reckless tariff policies to deliver higher inflation, economic slowdown and further falls in the dollar.

The interconnected government debt market may have become global, but it remains anchored by the US with the dollar still the global reserve currency aided and abetted by the US’s deep, liquid capital markets – a curse and a blessing. The blessing is that foreigners will still buy US debt because they necessarily hold dollars, but the curse is that they can and will hedge the risks through complex and expensive financial manoeuvres. The result is a financial edifice built on sand. But the first-round effect is to enable the US freely to borrow the money it wants, if at a price.

Britain’s sophisticated debt markets closely bind Britain to what is in effect a London/New York financial axis. Then, given our dismal inflation and growth prospects, the upward US interest rate pull can only impact badly on us. And if the US financial edifice ever blows up, Britain will be first in the line of fire.

Related articles:

Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves can only look at low EU interest rates with helpless envy, as wannabe PM Nigel Farage would have to. Even Italy’s bond yields are a good percentage point lower than ours, enjoying a dramatically lower risk premium than historically over its German counterparts – Berlin may now be loosening the purse strings to finance a vital €100bn military build-up, but the upward hike in its 10-year bond yields is still only to 2.6%. Nonetheless, Giorgia Meloni, Italy’s prime minister, raising military spending less sharply, boasts about Italy’s achievement. The markets aren’t stupid: they do recognise nuances of policy and prospects. At the same time, the euro is appreciating against the dollar as Big Money votes against the caprices of Trump’s US. The EU is built on better financial foundations.

Last year Britain sold a mind-boggling more than £250bn of government debt, close to 10% of GDP in total – financing both new borrowing and refinancing maturing debt. It has to do the same again this year and on top, weather the Trump effect hiking interest rates – all the time aware of wider systemic risks.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The smart British move must be to associate ourselves as much as we can with the EU to enjoy its halo effect, despite Trump’s attack, perhaps even volunteering more economic and financial collaboration. Britain, for example, should join the issue of a pan-EU war bond to raise funds at low euro interest rates for joint EU defence. Plainly, some taxes need to be lifted to pay for defence and our welfare system, requiring Starmer to level with the British public; others, such as stamp duty, lowered to boost growth. The bond markets are signalling the trap we’re in. Let’s try and escape it snapping shut.

Photograph by Andrew Harnik/Getty