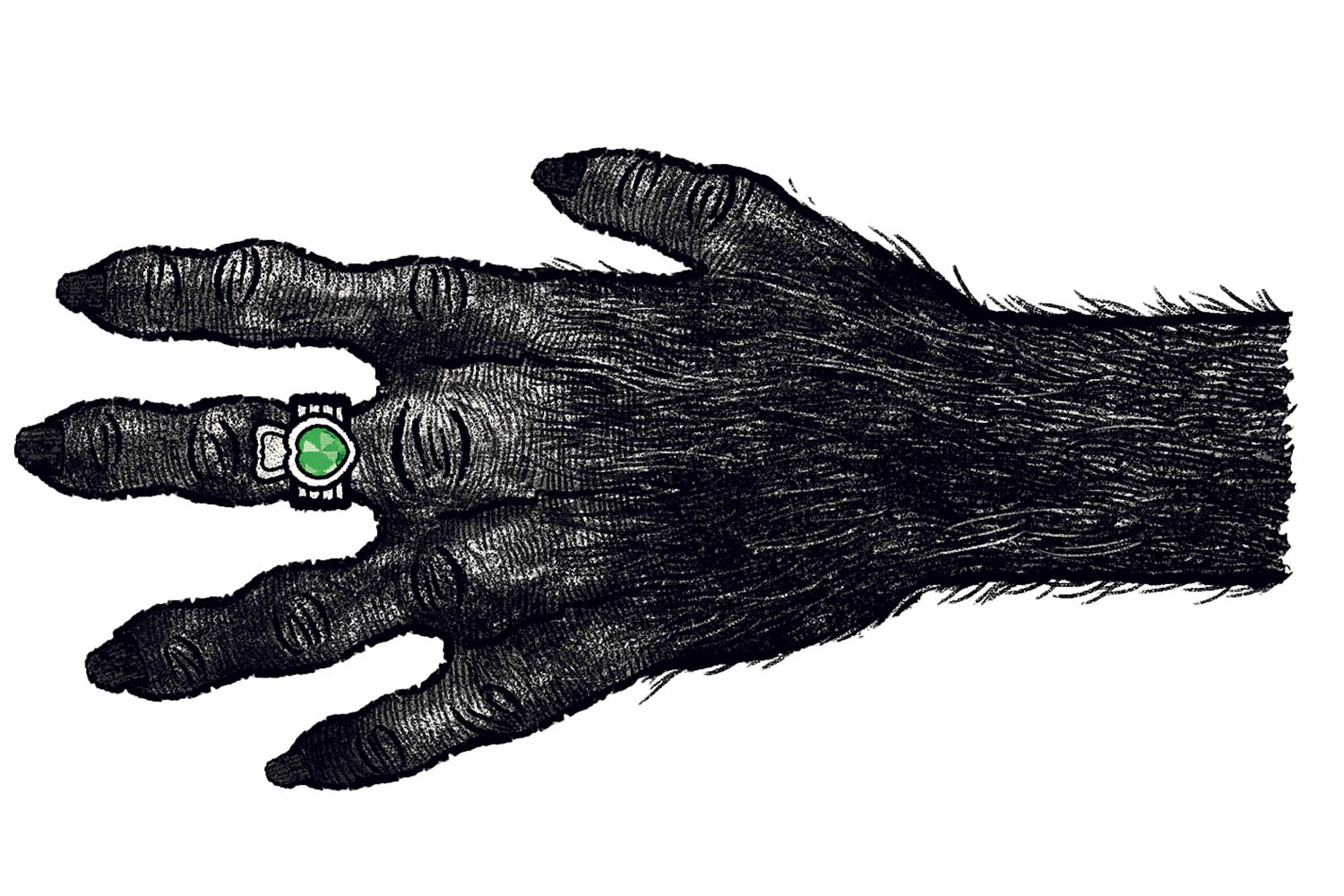

Illustration by David Foldvari

In 1902, a new short story appeared in Harper’s Monthly, written by the English author WW Jacobs. The story was a horror, in which a family – Mr and Mrs White, and their son Herbert – visit a friend who served with the British army in India. Over dinner, the friend shows them a mummified monkey’s paw. The paw has been cursed, he says. It will grant the holder three wishes, but each wish will also incur awful consequences as a punishment for meddling with fate. Today the story’s title, The Monkey’s Paw, has become in itself an allegory, a cautionary life mantra that says: be careful what you wish for.

You might, for instance, as the characters in the book do, wish for lots of money, but find that receiving it means it comes as a result of a bereavement. Or you might, if you were an Irish woman living in England, wish that being Irish was considered cool, only to discover that as a result of that finally happening, you are subsequently living in hell.

Once upon a time – the time being the year I moved to London – it was not considered “cool” to be Irish. Being Irish in London, or in England, was something to endure, a skill set that required you to be able to laugh heartily when men from the home counties mimicked your accent with affection and limited success – and in disbelief that this could be considered offensive. Nobody listened to Irish music, ate Irish food, or visited Irish places that weren’t the Giant’s Causeway. Knowledge of Ireland and the people within it was minimal at best. Once my flatmate asked me if they needed to get euros out before they went to Derry for the weekend.

And yet, years later, the monkey’s paw has curled its finger. Irishness is cool. It is veritably chic. It is omnipresent. Many of he capital’s busiest and most vibrant bars – the Devonshire in Soho, Finsbury Park’s Faltering Fullback – are Irish pubs. The phenomenon of the spice bag has transcended its humble, Dublin-based origins and gentrified itself at English street food markets and small-plates restaurants (costing minimum £9). Guinness is so popular as a drink and a pastime (in which men in their twenties, named Seb or Hugo, try to drink enough of the pint to split the “G” in Guinness exactly in half) that late last year London endured a drought of the black stuff. Pubs rationed it and put up signs advertising their other, less Irish stouts, instead.

Now, with the Guinness rivers safely flowing once again, England can look ahead to a particularly Irish summer. Irish musical acts headline festivals and dominate headlines, from Fontaines DC and Kneecap to CMAT and even second-generation dad-rockers Oasis. Ahead of their reunion, the Gallagher brothers have been keen to emphasise their Irish roots (their mother Peggy is from Mayo, their dad is from Meath). Noel has been spotted at Kneecap gigs and often talks about how his first exposure to music was the Irish rebel songs he heard in working men’s clubs around Manchester as a child. “We are Irish, me and Liam,” he said last year. “There is no English blood in us … Oasis could never have existed, been as big, been as important, been as flawed, been as loved and loathed, if we weren’t all predominantly Irish.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

I know, I know. What am I complaining about, right? This is all great. This is all Irish. This is all cool. But it’s also a form of a green soft power that is irritatingly flat, a reputation that doesn’t quite reflect reality. Is Oasis Ireland? Is Guinness? What about sad, horny men like Barry Keoghan and Paul Mescal? Chicken fillet rolls? Saoirse Ronan? Claddagh earrings? Sally Rooney novels for the girls; Paul Lynch novels for the boys? Jonathan Anderson running Dior, Seán McGirr running Alexander McQueen? These things are all wonderful, they’re all cool, but obviously they’re not all Ireland is. And as Cool Eire takes on more and more cultural power, that’s a reality that people are often perplexed and annoyed to uncover.

In May this year, CMAT bemoaned a new “fake version of Irish identity” built up and claimed by English people and Americans. “I didn’t relate to any of it”, she told Glamour. “Like, why am I seeing Claddagh rings everywhere? The GAA [Gaelic Athletic Association] jerseys? Why is everyone pretending we had this exact same childhood? There’s this very romantic vision of Ireland, but I grew up in a place where it’s not very fun to grow up.” The title song from her forthcoming album, Euro-Country, evokes that less-than-rose-tinted view of Ireland, post-2008 financial crash. A requiem for the Celtic Tiger, the song is about Bertie Ahern, male suicide and empty housing developments.

CMAT is right. Back home, Ireland is not just immersion heaters, Aran jumpers and deli counters. Pockets of far-right racism have instigated riots in Dublin and Ballymena. Earlier this month, bonfires in Belfast’s loyalist communities burned effigies of immigrants in small boats. Rent prices are so high and employment opportunities so limited that research published this year found one in eight 25-year-olds has already left the country. Of those who remain at home, another study suggests, 68% will remain living with their parents long into their late twenties. But acknowledging these aspects of Irishness is unchic, depressing, impolitic.

It’s “in” to be Irish, in other words, as long as you talk about it in a certain way. It’s chic to own a Brexit-busting burgundy passport courtesy of your Kerry grandmother (RIP), but not cool to espouse Irish political views that are thought of in any way radical. In particular, Irish criticism of British colonialism and solidarity with Palestine is seen as – to borrow a phrase from Ireland itself – beyond the pale. As one video from Dublin TikToker and writer Frankie McNamara puts it, “depoliticised and stripped of all radical analysis, Irishness on the world stage became a tale of cups of tea, Tayto and drinking”.

The monkey’s paw curls its finger, and every Irish person at home and abroad waits with bated breath for the wish to be granted. You’re cool now, guys! Fantastic news altogether! There’s a bit of shamrock-washing to be endured, sure. Put on the Pellador geansai, split the G, smile and enjoy it.