Illustration by David Foldvari

For as long as we’ve had impossibly high beauty standards, we’ve invented hacks, tricks and miracle cures to meet them – and then immediately ditched them once we’ve got there. During the Renaissance, receding hairlines were considered the pinnacle of glamour, and so women plucked their eyelashes and scalps to create the facade of a high, domed forehead; today, we opt for eyelash implant extensions and both men and women fill in their hairlines. In 2025 we want to be bronzed by sunbeds or with fake tans, but in the 17th and 18th centuries women so desired pale skin that they painted fake blue veins on their cleavage. Body hair was once thought so chic that women wore fake pubic wigs (known as Merkins), but the bush was out by the time Bush Snr was in. Ancient Japanese women blackened their teeth; today we have startlingly white veneers. Fifties housewives chewed handfuls of diet pills and barbiturates to look like the curvaceous postwar Hays Code women of Hollywood. Today, of course, we have Ozempic.

Technically a medication for diabetes, semaglutides have flooded the market and it’s become acceptable to describe these drugs as a silver bullet that will make you skinny, fast. No need to sweat, starve or accept your own body when Ozempic is around. And what began as a preserve of the rich is now for us mere mortals too.

Now, if you know the right websites to visit and lie about your BMI, anyone with a spare few hundred quid can get on Ozempic. You can even get it on prescription: last week Wes Streeting unveiled a 10-year plan for the NHS, with Ozempic front and centre. The newly slim health secretary said that the so-called “fat jabs” were the “talk of the House of Commons tea rooms”. “Half my colleagues are on them and are judging the rest of us saying: ‘you lot should be on them’,” he told LBC.

I am conflicted about this. On the one hand, this is improving NHS access to necessary medication based on need, rather than the ability to splash the cash on the side. This is, of course, a good thing. But the appetite for Ozempic is not limited to those with “clinical obesity”. If Streeting wasn’t aware of that himself, he wouldn’t be joking on the radio about Jaffa Cakes and Westminster tea-room conversations.

Ozempic has become a luxury item, a way to reach the beauty standard we’ve collectively pursued for decades, long after blue-veined boobs and blackened teeth had fallen out of fashion: thinness. From heroin chic and 1980s supermodel physiques to today’s “snatched” social media ideals, thinness has long been associated with youth, beauty, wealth and status.

The newly slim health secretary said that the ‘fat jabs’ were the ‘talk of the House of Commons tea rooms’

The newly slim health secretary said that the ‘fat jabs’ were the ‘talk of the House of Commons tea rooms’

In the past, it was Rubenesque figures that communicated wealth: the luxury to avoid working in the field, of having enough to eat. But as our culture changed, so too did the ideal body type, and the cult-like fervour with which we pined for it. I can’t remember a time when we didn’t culturally celebrate thinness but I also can’t remember a democratising force like Ozempic.

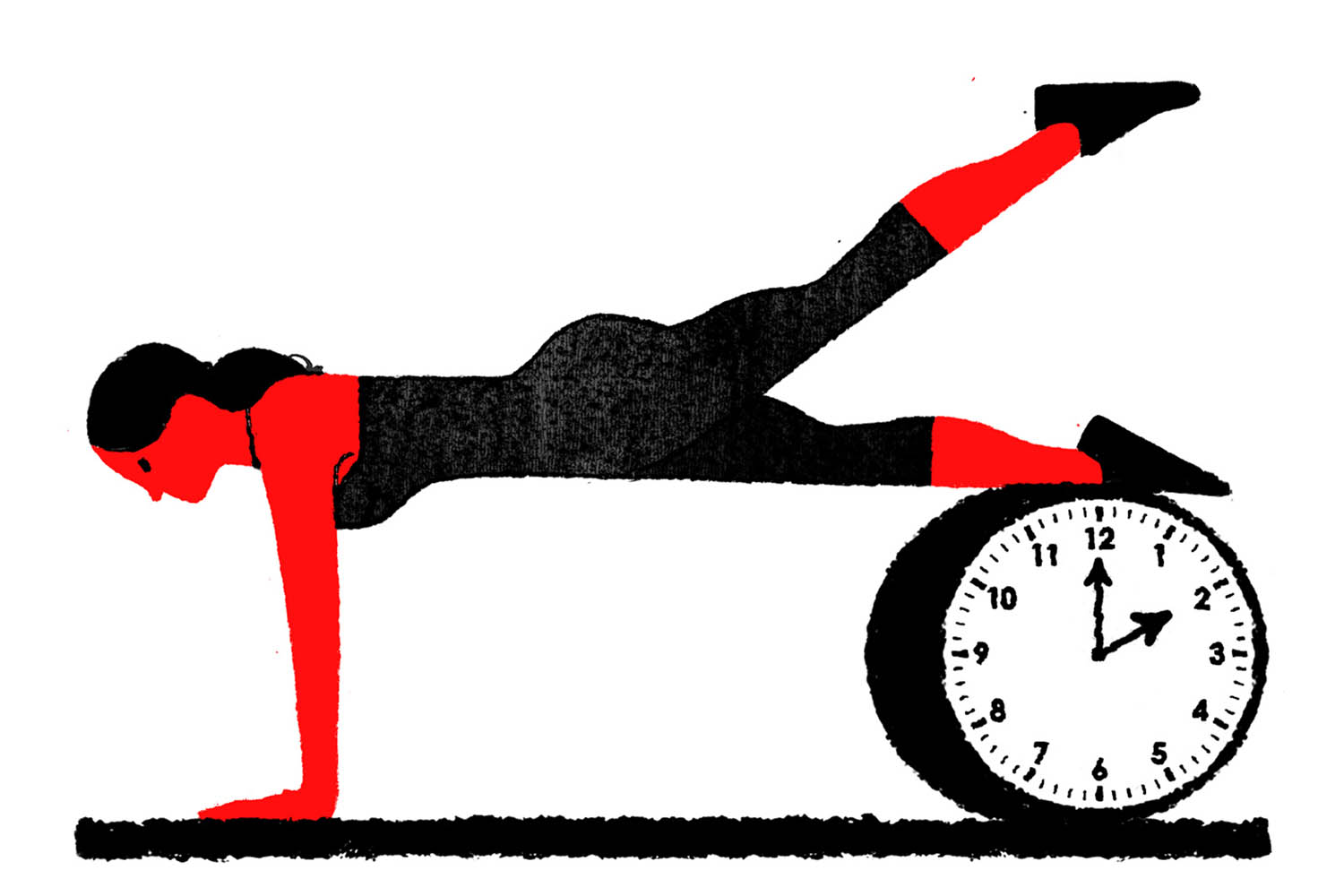

If Ozempic makes extreme thinness accessible, and therefore less desirable as a result, then what comes next? Enter: the post-Ozempic muscle mommy. Toned but not bulky, carefully feminised rather than overtly strong, the post-Ozempic muscle mommy represents 2025 ideals of luxury as much as blue-veined boobs or Rubenesque curves.

When Dua Lipa appeared on the cover of the most recent issue of British Vogue flexing her biceps, she became the latest poster-girl for a growing trend for “pilates arms” among “pilates girlies”. Noticed an influx of reformer studios in your area recently? Seen the girls queuing outside them, looking bored and serene, clad in matching Birkenstocks, clutching iced matchas? Of course you have. Did you think to yourself: “It’s 2pm, don’t any of these women work”? Of course you did. If mass-market Ozempic means that thinness alone can’t be aspirational, then perhaps time itself is the new luxury. Specifically, the time to exercise.

Fitness trends and changing body ideals don’t exist in isolation, they tell us something about our culture more widely. As a recent New York Times piece put it, “pilates is political”. The article was referencing a viral video posted by MaryBeth Monaco-Vavrik, a 24-year-old political science graduate and barre instructor. Monaco-Vavrik linked a rise in popularity of pilates and running and the decline of strength-training exercises to an increase in American authoritarianism. Pilates, the most popular option on ClassPass in 2024, can cost more than £30 for 50 minutes. It requires specialised kit and cult-like devotion to secure your space. When society becomes more socially conservative, Monaco-Vavrik theorised, we long for smaller, lither bodies.

I think she’s on to something. If mass-market Ozempic encourages a decline in expensive diet products, then expensive “feminine” exercise routines are the replacement. If anyone can be thin, this theory goes, then how to differentiate yourself unless you are thin but also subtly muscular? Unless you’re etching on your abs through still expensive and experimental plastic surgery – as Drake was ridiculed for doing in a selfie this week. Having the leisure time to exercise has become the new flex.

Ozempic might seem exciting to us now but, as with all beauty standards, the derision begins as soon as it goes from aspirational to accessible (BBLs stopped being just for Kardashians; celebrity veneers became “Turkey teeth”; lip fillers went from A-listers to Love Islanders). Already there are the beginnings of a post-Ozempic snobbery, a civil war in the food and fitness worlds, instigated by those who think losing weight on the drug is “cheating”. We’ll always invent a new, higher standard to reach, a new miracle hack, a new ideal to chase for, a new way to valorise wealth. During a cost-of-living crisis and an attention-deficit economy, our free time – and what we do with it – is the only ideal of perfection left.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy