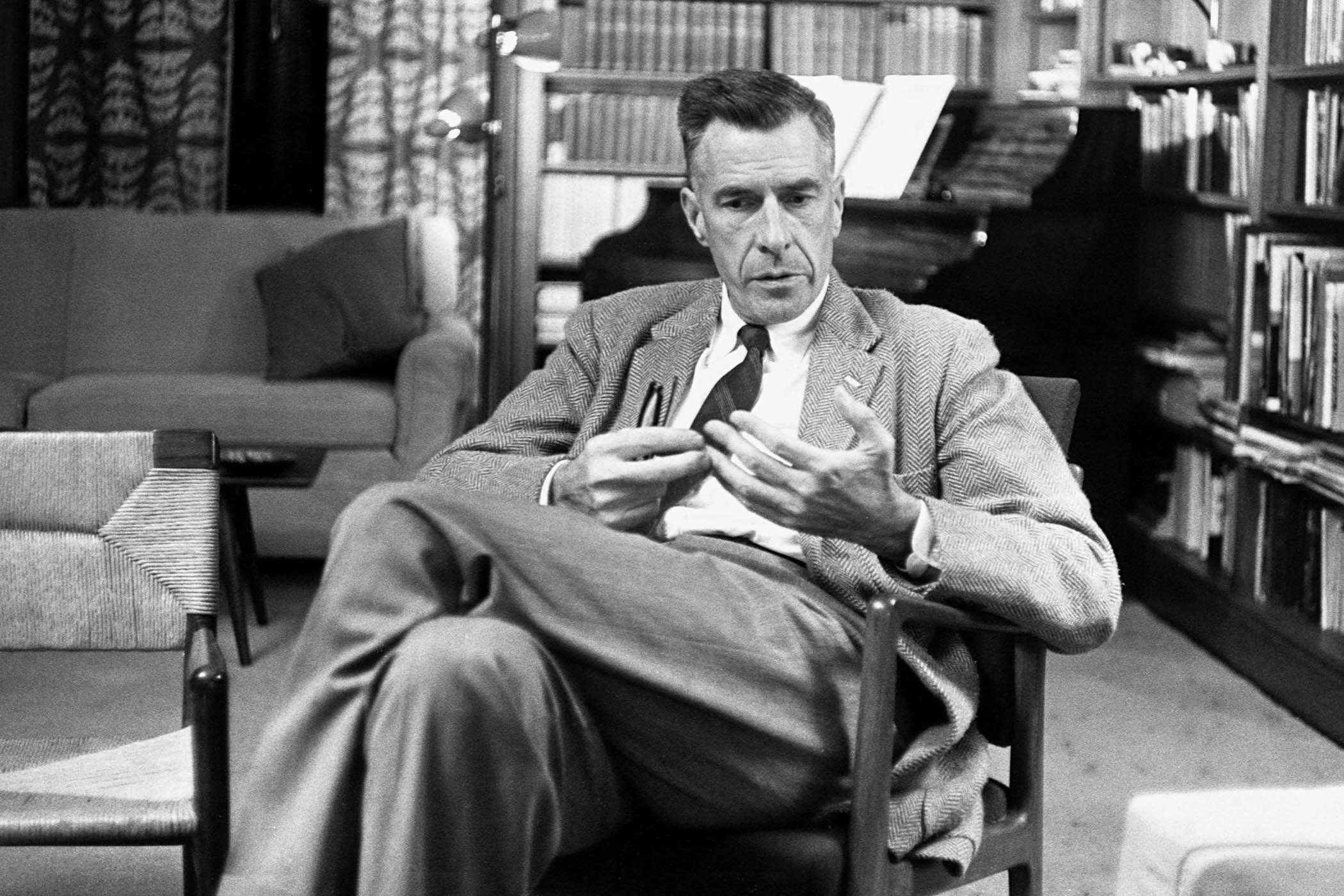

In 1954, while working on The Affluent Society, the economist John Kenneth Galbraith paused to compose an elegant little history of the days preceding the crash that triggered the Great Depression. The resulting book, The Great Crash 1929, came out in 1955 and sold like hot cakes. “I never enjoyed writing a book more,” Galbraith recalled afterwards, and readers could confirm that as they made their enjoyable way towards his sardonic conclusion: that the common denominator of all speculative bubbles is the belief of participants that they can become rich without doing much (or indeed any) work.

Revised editions of the book, each time with updated research and a more timely version of the introduction written by Galbraith, were published in 1961, 1972, 1988, 1997 and 2009. (It remains in print today as a Penguin Modern Classic.) At one point, someone asked him what was the point of continually looking back to what was becoming ancient history. He replied that it was the task of the historian “to keep fresh the memory of such crashes, the fading of which correlates with their reoccurrence”.

In that spirit, let us consider the AI bubble inflating around us – and the crash that will follow when it bursts. And if you are in any doubt about whether there is a bubble, the governor of the Bank of England will happily put you right. He chairs the bank’s financial policy committee, which warned on 8 October that “equity market valuations appear stretched, particularly for technology companies focused on artificial intelligence (AI). This, when combined with increasing concentration within market indices, leaves equity markets particularly exposed should expectations around the impact of AI become less optimistic.”

Translation: US stock valuations are at extreme levels not seen in decades. Five large companies account for 30% of the S&P 500’s valuation – the most concentrated the index has been in 50 years. There are now nine $1tn-plus tech companies: as I write, Meta is closing in on $2tn, Amazon has past the $2tn mark, Google parent Alphabet now is worth $3tn and Apple $3.7tn, while this summer, Nvidia became the first $4tn company. So when the air goes out of the balloon, the damage will be widespread – including to everyone’s pension funds.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Then there’s the money that tech companies are putting into AI. Amazon, Microsoft, Google, Meta, OpenAI et al are spending it like it’s going out of fashion. They’re proposing to spend between $300bn and $400bn every year on AI for the next few years. McKinsey, the big consultancy, thinks that by 2030 AI infrastructure spending could reach $6.7tn. If there’s a business plan that shows how reasonable rates of return can be obtained on investments on this scale, then nobody’s seen it yet.

So this is an industry running mostly on hype and inflated expectations. The latter are like catnip for the suckers, fools and shysters who Galbraith wrote about – the people who claim or believe that numbers always go up. And irrational expectations are rife in the AI stampede.

Which, of course, is great news for opportunistic entrepreneurs founding AI companies and being deluged with investors’ money. An outfit called Artisan, for example, ran a cheeky “Stop hiring humans” billboard campaign on the New York subway, encouraging people to vandalise its posters. It was an imaginative stunt that got it $25m in first-round funding. What does it do? Merely uses AI “agents” to replace humans doing repetitive work. Useful, perhaps, though not exactly rocket science – but it has the magical AI tag.

Or consider Thinking Machines Lab, a startup founded by former OpenAI executive Mira Murati and a number of others from the chatbot maker, which immediately got $2bn in funding and is now apparently valued at $12bn. What does it do? Hard to say, other than that it is “building AI systems that push technical boundaries while delivering real value to as many people as possible. Our team combines rigorous engineering with creative exploration, and we’re looking for collaborators to help shape this vision.”

Galbraith would have had some fun with this vacuous cant. It might even have persuaded him to update his famous aphorism: now it is AI, rather than economic, forecasting that “exists to make astrology look respectable”.

What I’m reading

Web of influence

It’s the Internet, Stupid is a thoughtful essay by Francis Fukuyama on why populism thrives.

Far from oblique

Infinite Wibble: Brian v. Eno is Ian Penman’s insightful essay for the London Review of Books.

Beyond borders

Noema’s A Diverse World of Sovereign AI Zones asks how virtual territories will reshape geopolitics.

Photograph by Getty Images