On 7 August, OpenAI launched its latest leading large language model (LLM), GPT-5, and in the process learned the hard way that, if you’re in the marketing business, you should always manage users’ expectations.

For a long time, the chatbot maker’s chief executive, Sam “Babyface” Altman, had been assiduously talking up the supposed capabilities of his new model. It would, for example, be “a significant step along the path to AGI [artificial general intelligence]” – not to mention “a quantum leap in AI” that “bridges the digital divide, offering personalised and accessible technology solutions for all”. Interacting with it would apparently be “like talking to ... a legitimate PhD level expert in anything, any area you need on demand that can help you with whatever your goals are”. And so on, ad infinitum.

You can guess what happened. The launch was a fiasco. The general consensus was that the new model is at best serviceable and competent. “GPT-5 just does stuff, often extraordinary stuff, sometimes weird stuff, sometimes very AI stuff, on its own,” wrote business school professor Ethan Mollick, an experienced user of these tools. So it’s interesting, and no doubt useful. But a threshold to AGI, it ain’t. It’s an improvement on what went before, not a quantum leap. Maybe it should have been called GPT-4.5.

However disappointing the PR disaster might be for OpenAI, it’s useful for the rest of us because it undermines a pernicious myth that passes for holy writ in the tech industry. This is the supposed “scaling hypothesis”, which says that the bigger an AI model is, the more powerful it will be.

The current AI arms race to carpet the globe with datacentres is driven by the belief that if we increase the amount of data and “compute” – computational power – that go into LLMs, then eventually we’ll arrive at what physicists call a “phase transition”, such as when water changes to ice or to steam, and we will have true AGI.

At the moment, an entire industry is betting its metaphorical ranch on this horse, with all the “externalities” in terms of pollution, energy and water consumption and material extraction that it brings with it. So wouldn’t it be ironic if it turns out that the race is futile because a horse is the wrong kind of animal? It’s a perfectly good competitor, but it’s never going to morph into Einstein. And, by the same token, no LLM is ever going to morph into a truly superintelligent agent because intelligence isn’t actually in its DNA.

The strange thing is that we all know this. We know how LLMs work; that they are just “stochastic parrots” that construct coherent sentences by deciding which word is the most probable one to choose next based on statistical patterns.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

We are aware that they don’t really “know” anything and have no knowledge of the world beyond what we tell them. We know that what they provide as answers are lousy reproductions of what they have ingested in their training. And yet we persist in thinking – or pretending – that they are somehow “intelligent”. Why?

The answer is the Eliza effect, named after the computer program written by the MIT researcher Joseph Weizenbaum in the 1960s. It was basically a script that simulated a psychotherapist of the Rogerian school (in which the therapist often reflects back the patient’s words to them) with which people could interact by typing on a keyboard.

Weizenbaum was surprised to discover that some people, including his secretary, were attributing humanlike feelings to the machine. As Róisín Lanigan nicely documents in her column this week, the Eliza effect has now gone unstoppably mainstream.

In a groundbreaking new book, Language Machines, the American scholar Leif Weatherby goes to the heart of the matter: our tendency to confuse linguistic fluency with intelligence. His central argument is that if we are to properly understand LLMs, we need to accept that linguistic creativity can be completely distinct from intelligence, and that text doesn’t have to refer to the physical world – just to other words. What these machines demonstrate is that language works as a system of signs that mostly refer just to other signs.

If that reminds you of the French literary philosopher Jacques Derrida, join the club. He saw language as a self-contained system, which is a good description of what goes on inside an LLM. For the machine, words only refer to other words rather than having a relation to external reality.

This means that any sequence of words generated by an LLM is derived solely from its relationship to other words within the linguistic system, not from any “understanding” of the physical world. But that doesn’t prevent it from producing chatty, plausible text – or the human user from ascribing “intelligence” to it on that account. So maybe GPT-6 should be named Derrida 1.0.

What I’m reading

Making plans for Nigel

Trump’s Apprentice is a fine piece of reporting by Sam Bright on how Trumpism is coming to British politics by way of Nigel Farage.

Manhattan transfer

The economist Branko Milanović offers some sharp observations on Substack in How to Learn About Politics from Two Democratic-Leaning Women in New York.

Religious calling

Could Project 2025 Happen Here? is a useful wake-up call by Peter Geoghegan on the American Christian right’s plans for Britain.

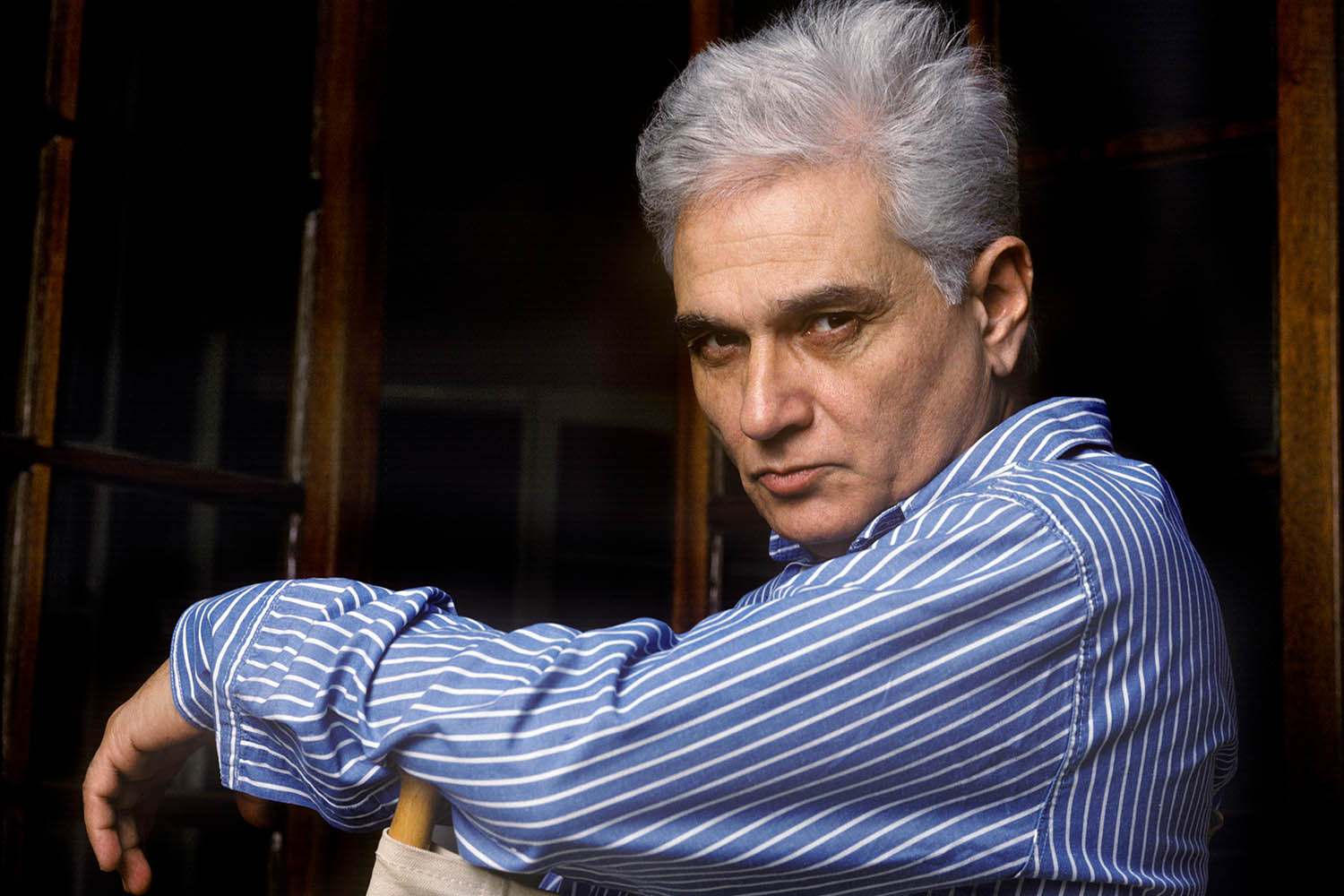

Photograph by Ulf Andersen/Getty