At a tribunal in Southampton last week, Robert Watson, a software engineer at Roke Manor Research, won his case for unlawful dismissal under the Equality Act 2010 on the grounds of disability discrimination.

The case led to ill-informed accusations that the manager involved in the legal action had been punished for sighing at an employee. This is a common accusation made against claims of sexual harassment: that, although once upon a time the office was rife with unpleasant sexual approaches, these days nobody can so much as look at another colleague without inviting a lawsuit. In point of fact, the number of cases of harassment brought to employment tribunals has been stable for a decade.

So what is the truth, in law and in practice, about cases of sexual harassment?

What is the law?

Sexual harassment did not feature in UK law until June 1986. The Sex Discrimination Act (SDA) of 1975 had made it unlawful to treat a woman “less favourably” than a man but made no mention of sexual harassment. In December 1983, the Labour MP Jo Richardson introduced a private member’s bill on sexual harassment to the Commons but a predominately male chamber did not allow the bill a second reading.

Sexual harassment instead came into statute through case law. In 1986, Jean Porcelli, a school laboratory technician employed by Strathclyde regional council, brought a case against the lewd insults of two male colleagues that three judges in the court of session ruled constituted sexual harassment under the terms of the 1975 legislation.

A strict definition of sexual harassment is, of course, elusive. The Equality Act 2010 defines harassment as unwanted conduct “which has the purpose or effect of violating an individual’s dignity or creating an intimidating, hostile, degrading, humiliating or offensive environment”. There is an echo here of an infamous legal case in the US. In 1964, Justice Potter Stewart ruled, during the obscenity case Jacobellis vs Ohio, that Louis Malle’s film The Lovers could safely be issued. When he was asked how he was defining hardcore pornography, Stewart said that was difficult but: “I know it when I see it.”.

Sexual harassment is, though, cast in law. In addition to the provision of the Equality Act 2010, the Worker Protection (Amendment of Equality Act 2010) Act, which came into effect on 26 October 2024, introduces a legal duty on employers to take reasonable steps to prevent sexual harassment of their workers.

The recent case involving McDonald’s shows what this vicarious liability might mean in practice. In February 2023, after numerous complaints from employees, McDonald’s signed a legally binding agreement with the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) in which it pledged to protect its staff from sexual harassment.

Related articles:

The company’s chief executive, Alistair Macrow, admitted to the business and trade select committee in November 2023 that McDonald’s UK had received 407 employee complaints since July 2023. More than 700 current and former junior employees are now taking legal action against the company for failing to protect them.

In March 2025, in the light of the new Equality Act guidance about preventing sexual harassment in the workplace, the EHRC wrote to every UK branch of McDonald’s to warn them that “a failure to take reasonable steps to prevent sexual harassment would therefore constitute an unlawful act”.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

How common is sexual harassment?

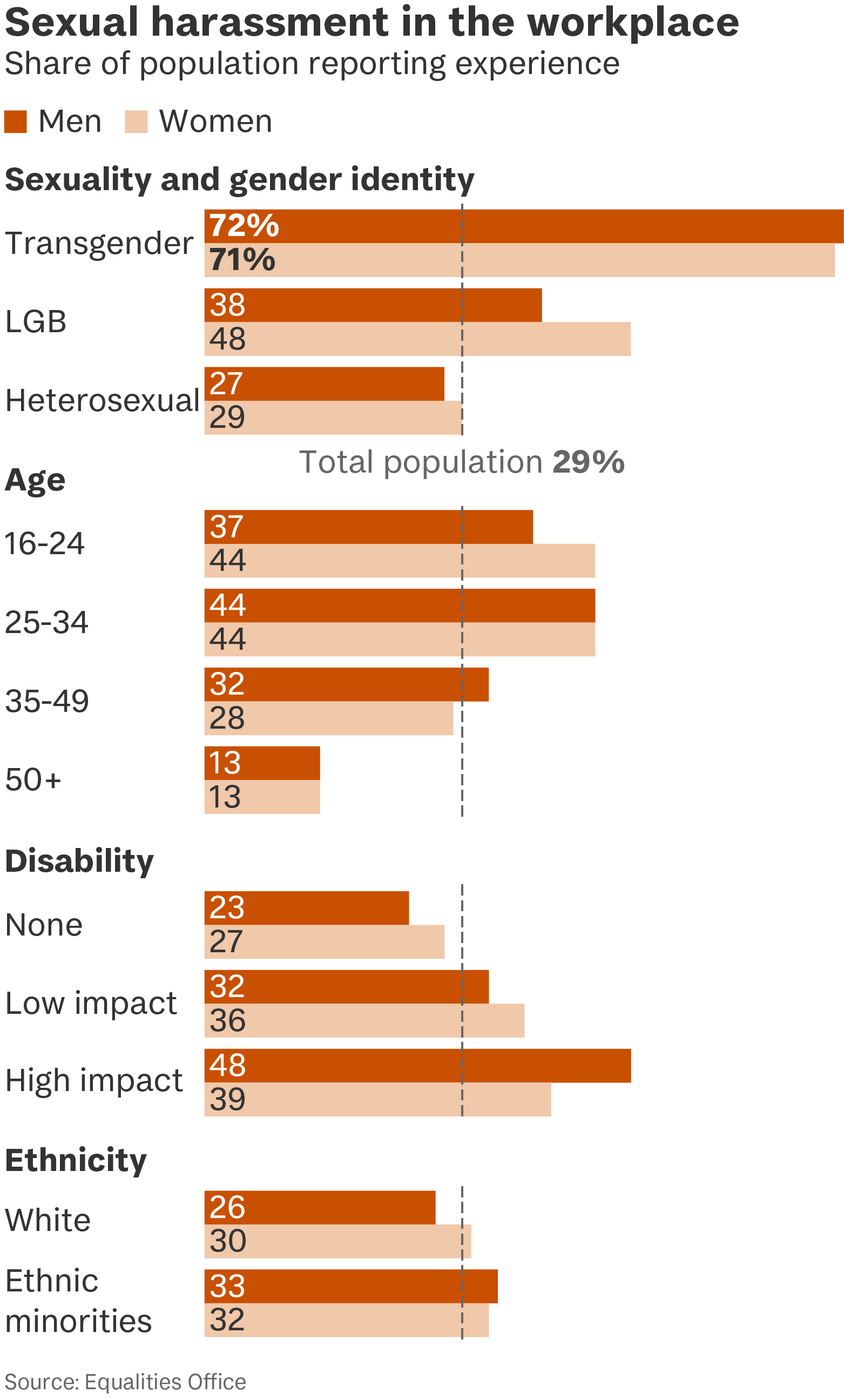

The honest answer is that we hardly know. The UK has only ever done one proper sexual harassment survey, which came from the Government Equalities Office in 2020. It found that 29% of those in employment had experienced some form of sexual harassment in their workplace over the previous year.

Unwelcome sexual jokes and unwanted staring were the most common forms of sexual harassment cited. Almost two-thirds of those who had experienced sexual harassment in the workplace in the previous 12 months reported that the perpetrator was a man, and about a quarter (22%) reported it was a woman. Twenty per cent of those in employment experienced sexual harassment at their place of work. Sexual harassment when socialising with colleagues outside the workplace was the second most likely setting (13%), followed by visits to clients or customers (9%).

It is telling that, despite the prevalence of sexual harassment, only 15% of people reported their experience. Among those who did so, half considered their jobs had changed as a result. The most common outcome for the victims was that they looked for new employment (17%). Two-fifths said there were no consequences for their perpetrator.

It is telling that only 15% of people reported their experience. Half considered their jobs had changed as a result

It is telling that only 15% of people reported their experience. Half considered their jobs had changed as a result

More recent surveys have produced lower numbers, though it is likely that the answers are sensitive to different forms of question, rather than picking up a genuine decline in the incidence of sexual harassment. The Crime Survey for England and Wales for 2023 suggested that 8% of women and 3% of men had experienced sexual harassment in the previous year. University College London published a report this year called How Common is Workplace Abuse? It found that 4.1% of women had experienced sexual harassment in the workplace.

The absence of good data is demonstrated by the fact that the TUC’s Still Just a Bit of Banter? report, published in 2016, remains so widely cited. The TUC found that 52% of the 1,500 women polled had experienced some form of sexual harassment, 32% had been subject to unwelcome jokes of a sexual nature, nearly a quarter of them had experienced unwanted touching and a fifth had experienced unwanted sexual advances. Four out of five women did not report the sexual harassment.

What next?

It would be naive to doubt the prevalence of sexual harassment, no matter the paucity of the data. No government agency is collecting good data, which makes comparisons over time impossible. This, of course, ought to be remedied. In the meantime, the legislative framework does provide some recourse for victims of sexual harassment, and the most conspicuous finding, as far as we know, is not that there is an abundance of frivolous claims but that there is still a lot of bad behaviour going unreported.