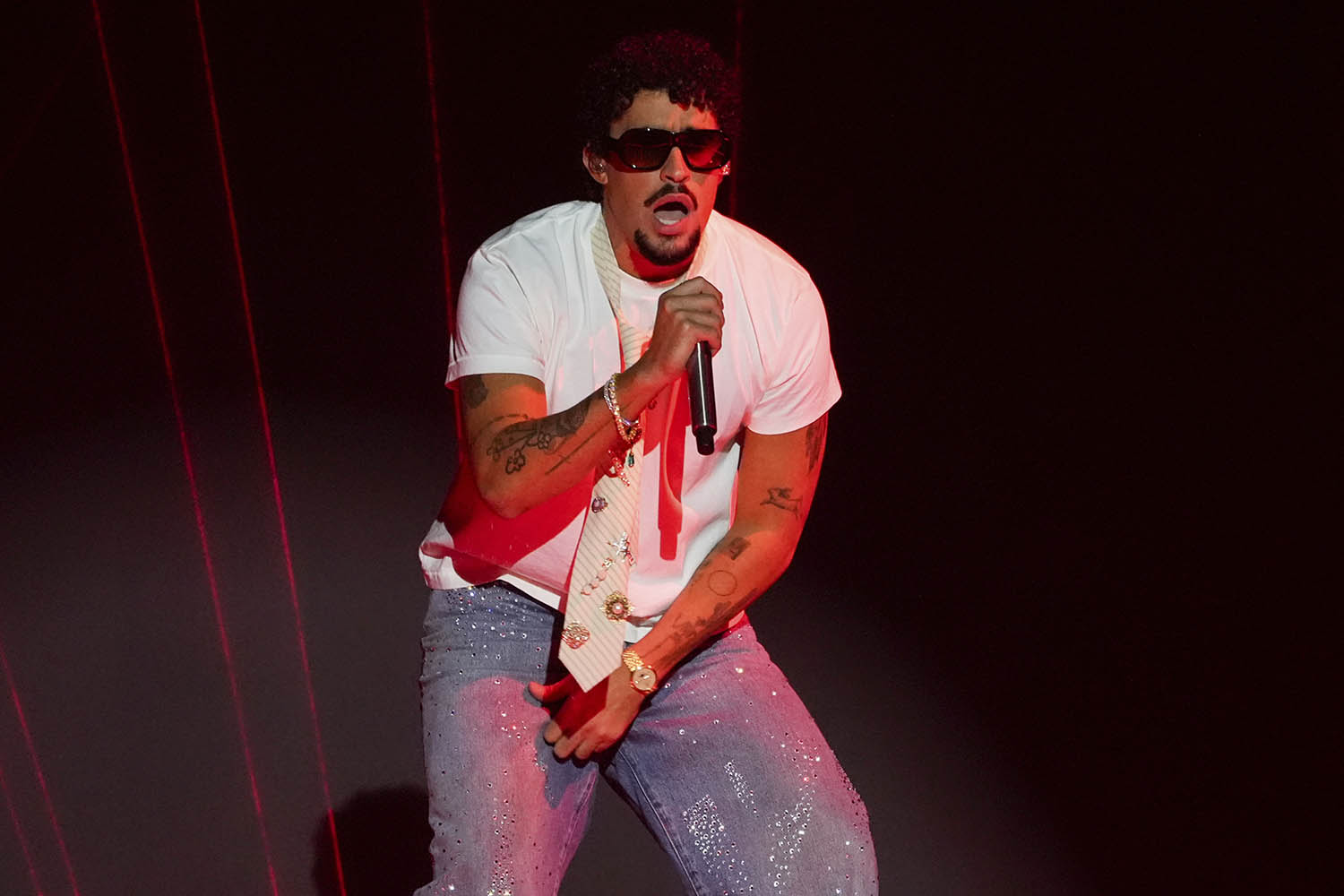

“I’m from P fuckin’ R,” raps Bad Bunny, before a frenzy of congas and squealing horns builds La Mudanza to its riotous conclusion. The salsa-rap track transports you to San Juan’s barrios, where rhythm-loving Puerto Ricans have stamped and spun to salsa for decades.

La Mudanza closes Bad Bunny’s sixth album, Debí Tirar Más Fotos. It is a bold assertion of Puerto Rican identity that inscribes the island’s Afro-Latino sounds –bomba, plena, salsa – into the musical mainstream and cements his status as one of the most innovative artists around.

This week, he kicks off his loudest, proudest celebration of his homeland to date: a two-month residency in San Juan. With the tour, aptly titled I Don’t Want to Leave Here, Bad Bunny puts Puerto Rico on the map. “It’s amazing because he’s welcoming the entire world into his world,” says a veteran of the Latin music industry.

Thanks to his huge following, he can afford to take creative risks. Bad Bunny’s event is this summer’s hottest ticket on the island: around 400,000 sold out in just four hours, and hotel bookings are at an all-time high. It is a taste of what’s to come this autumn, when he begins his world tour through sold-out stadiums in Europe, Latin America and Asia.

Bad Bunny is the most famous rumbero leading a revolution in Latin music. But it didn’t start with him. Reggaeton grew out of Puerto Rico’s nightclubs in the 1980s, and Latin America has danced to it for the past decade. Shakira, Colombia’s J Balvin and the “King of Reggaeton” Daddy Yankee paved the way for today’s generation of stars.

It is very powerful that the biggest pop star is using music many Colombians have dismissed

It is very powerful that the biggest pop star is using music many Colombians have dismissed

Silvana Rozo from the law firm that has represented Karol G

Boosted by streaming, social media and the rise of the Hispanic population in the US, reggaeton is now the soundtrack to perreo dancing from Mexico City to Miami, from Madrid to Manila. According to Luminate, which tracks streaming viewership, streams of Latin music in the US have increased by 352% since 2018, hitting 113bn in 2024.

Bad Bunny and the Colombian singer Karol G are two of the genre’s most prominent artists, their world-conquering albums breaking new ground for Spanish-language music, followed by Grammys, record-shattering global tours and documentaries. Drake, Shakira, Manu Chao and Rosalía are among their international collaborators. These double acts boost their status: Despacito, by Puerto Rican Luis Fonsi and featuring Daddy Yankee, dominated the charts in 2017, partly because of a remix with Justin Bieber.

As these artists evolve reggaeton’s sound, new audiences are being turned on to Latin music. The release of Debí Tirar Más Fotos in January made Bad Bunny the most streamed artist in the world, claims Luminate; his tracks being played 3bn times that month alone. Si Antes Te Hubiera Conocido, Karol G’s merengue hit from her latest album, Tropicoqueta, was the longest-running No 1 on Billboard’s Latin Airplay chart.

Related articles:

What connects these two records is how they weave traditional Latin sounds with urban music. Bad Bunny and Karol G are transforming how the region sees itself.

Yet this Latin dance party has political overtones. “They want to take away my river and also the beach/They want my neighbourhood and they want my grandmother to leave”, Bad Bunny laments on Lo Qué Le Pasó A Hawaii. It is a cry against the gentrification and influx of foreign money dispossessing Puerto Ricans of their island, and the country’s history of exploitation, which is a US territory. “They killed people for waving the flag,” he sings in La Mudanza.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Only Spanish-speakers will understand his Puerto Rican slang. Yet the language barrier doesn’t matter, says Nir Seroussi, executive vice-president at Interscope Geffen A&M, which signed Karol G in 2023.

Bad Bunny is authentic and witty. He “stands for the liberation of creativity,” says Seroussi. “Nobody likes to feel like they’re chained, or that they have to conform… that’s what he represents.” Karol G’s Tropicoqueta album is less overtly political, though just as disruptive. She revisits her influences in 20 songs that roam across the region: from steamy cumbia (Cuando Me Muera Te Olvido), to accordion-inflected vallenato from Colombia’s Caribbean coast (No Puedo Vivir Sin Él); to Mexican folk (Ese Hombre Es Malo – a nostalgia-soaked ballad recorded with a 57-piece mariachi band.)

Even the album cover, in which Karol G is sprawled across three drums wearing a flower-power bikini, is a tribute to the genre. Every year since 1961, Discos Fuentes, Colombia’s first record label, has released 14 Cañonazos Bailables, a compilation of hits that champion the Afro-Colombian, campesino and indigenous musicians. For seven decades, the LP has featured a skimpily dressed mamacita on its sleeve.

She is reclaiming Colombian identity, says Silvana Rozo of The Artist’s Attorney, a Colombian law firm that has represented Karol G. “We have internalised the cultural dominance of the US so much that we have rejected our own culture,” says Rozo. “It is very powerful that the biggest pop star is using music many Colombians have kind of dismissed.”

The Latin music explosion is shifting the aspirations of younger musicians away from the US. Seroussi recently met some young Latin artists who had heard of neither Eminem nor Drake. “This is impressive… American culture used to be the holy grail,” he says.

Karol G and Bad Bunny are spearheading a wave of action at a time when Donald Trump is vowing to deport millions of Latinos. Both artists have spoken up in defence of migrants’ rights. Silvana Rozo says: “Trump wants Latinos out of the territory, but he can’t get us out of the charts."

Photograph by Invision/AP