Over the past few years, 7 September – Brazil’s Independence Day – became the stage for Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s far-right former president. He turned a holiday traditionally overseen by the armed forces into a display of political muscle, filling the streets of São Paulo, Brasília and Rio de Janeiro with tens of thousands of supporters.

This year will be different. The celebration will take place without the former president or his closest officers. Instead, Bolsonaro and seven allies, six of them military or ex-military, will be appearing in Brazil’s supreme court, accused of attempting a coup following his election defeat to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.

On 8 January 2023, a week after Lula was inaugurated as president, thousands of Bolsonaro’s supporters stormed official buildings in Brasília, demanding “military intervention” to topple the newly elected leftwing president, an echo of the January 6 attack in Washington. Bolsonaro now faces trial for inciting the crowds and conspiring with military allies to stage a coup d’etat. The plan allegedly included a plot to assassinate Lula, vice-president Geraldo Alckmin and supreme court justice Alexandre de Moraes. Bolsonaro is currently under house arrest for violating a court order that barred him from communicating via social media.

It is the first time a former president will stand before the country’s highest court accused of undermining democracy. But perhaps more importantly, it is also the first time senior figures from the armed forces will stand trial – a moment that many Brazilians have long hoped for.

Brazil endured two decades of dictatorship from 1964 to 1985, but after the return of democracy, the armed forces faced no moment of reckoning. Ever since, there has been “this idea that the military are guardians, able to moderate situations with very little consequence, arbiters of the nation’s destiny”, said Anthony Pereira, director of the Roger Thayer Stone Center for Latin American Studies at Tulane University. “This trial is a real chance for Brazilian democracy to move beyond that.”

A former captain himself, Bolsonaro repeatedly praised the dictatorship and its enforcers, most notoriously in 2016, when, as a congressman, he dedicated his impeachment vote against president Dilma Rousseff to Colonel Brilhante Ustra, who had tortured her during the regime. Once in power, he went further, officially commemorating the anniversary of the 1964 coup. The number of military personnel in government posts more than doubled during his four years in office.

Bolsonaro was able to draw on that legacy because Brazil’s dictatorship was unlike other Latin American regimes. It lasted longer: 21 years (Argentina, for example, endured only seven). And it did not end in rupture, but through what the military regime described as a “slow, gradual and safe opening”. This process culminated in the indirect election of a civilian president in 1985 via delegates chosen by the junta.

An enduring notion took hold that the Brazilian regime had been “softer” than others. While Argentina counts about 30,000 killed or missing, the official number in Brazil is 434.

Related articles:

“The lower number in Brazil is due to the fact that the government had absolute control over society,” says Pedro Dallari, who led the National Truth Commission, which investigated abuses during the regime. “There was no dissent even within the regime itself. The military did not kill more simply because they didn’t need to. There was a systematic policy of eliminating enemies.”

The result was that, unlike its neighbours, Brazil never held perpetrators accountable. Argentina put top junta leaders on trial in 1985 and overturned amnesty laws. Chile also prosecuted officials, including general Augusto Pinochet himself, who was indicted and arrested in the 1990s. Meanwhile, Brazilian law in 1979 pardoned all those involved in political conflict during those years—not only political dissidents, but also state agents.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

‘This trial is a real chance for Brazilian democracy’

‘This trial is a real chance for Brazilian democracy’

Anthony Pereira,Tulane University, US

But Rousseff paid a political price. When she was controversially impeached in 2016, accused of fiddling the books to make the budget surplus appear larger, segments of the military quietly supported the move. Her successor, Michel Temer, took note and brought the military closer to the government. In 2018, for example, he gave the armed forces extraordinary powers over public security in Rio de Janeiro.

It was not until Rousseff set up a National Truth Commission in 2012, to investigate abuses committed during the dictatorship, that the state began to take action. Its final report, released two years later, named more than 370 state agents responsible for torture, killings and disappearances.

But now it appears military men may be held accountable. One reason is that the investigation into the alleged coup revealed that the armed forces are far from united. According to federal police, Bolsonaro showed a draft coup decree to Brazil’s three top commanders, and only the head of the navy supported it. The leaders of the army and air force rejected the plan, and one even threatened to arrest him, the inquiry concluded.

“Individual officers are now involved, but not the armed forces as an institution,” said Dallari. The trial has been tense. De Moraes instructed military defendants not to appear in uniform after a group of them did so. “The accusation is directed at officers, not at the Brazilian army as a whole,” he said.

A conviction is widely expected. Even if acquitted, Bolsonaro still cannot be a candidate in next year’s presidential elections. He was barred from running for office in 2023 by the electoral courts for claiming, without evidence, that Brazil’s electronic voting system was fraudulent. The 70-year-old former president could face a sentence of more than 40 years, which he would likely serve under house arrest due to his age. If officers are found guilty, it could show Brazil’s democracy is finally strong enough to push the military back into the barracks.

This reckoning extends beyond the coup trial. In 2025, the Oscar-winning film I’m Still Here, which tells the true story of a family whose father was killed by the regime in the 1970s, sparked renewed public debate over the legacy of the dictatorship. The movie’s success fed to broader discussions about memory, justice and accountability, and even prompted the supreme court to reopen the debate on whether torture under the dictatorship should still be prosecutable, no matter how long ago.

But guilty verdicts could lead to a backlash at the ballot box. The cohort of officers who rose to prominence alongside Bolsonaro can still run for office. Between 2000 and 2024, the number of candidates who used military ranks in their ballot names in elections grew by 70%, according to a study. Together with former police officers turned politicians, they make up the so-called bancada da bala – the bullet bench – an informal bloc of pro-gun legislators which holds 263 of the 513 seats in Congress.

Their presence could grow further, as one-third of Brazilians view violence as the country’s main problem and look admiringly at mano dura (“iron fist”) leaders elsewhere in Latin America, such as Nayib Bukele in El Salvador. Lula, who has been signalling he could run for a fourth term, has been pushing public security bills. Bolsonaro, who has three sons in politics and several governor allies competing for his blessing, has yet to choose a political heir.

More than 40% of Brazilians say Bolsonaro should not be convicted – and that sentiment may extend to his fellow men in uniform. The generals may lose in the courtroom, but at the ballot box many still rally to them.

Timeline

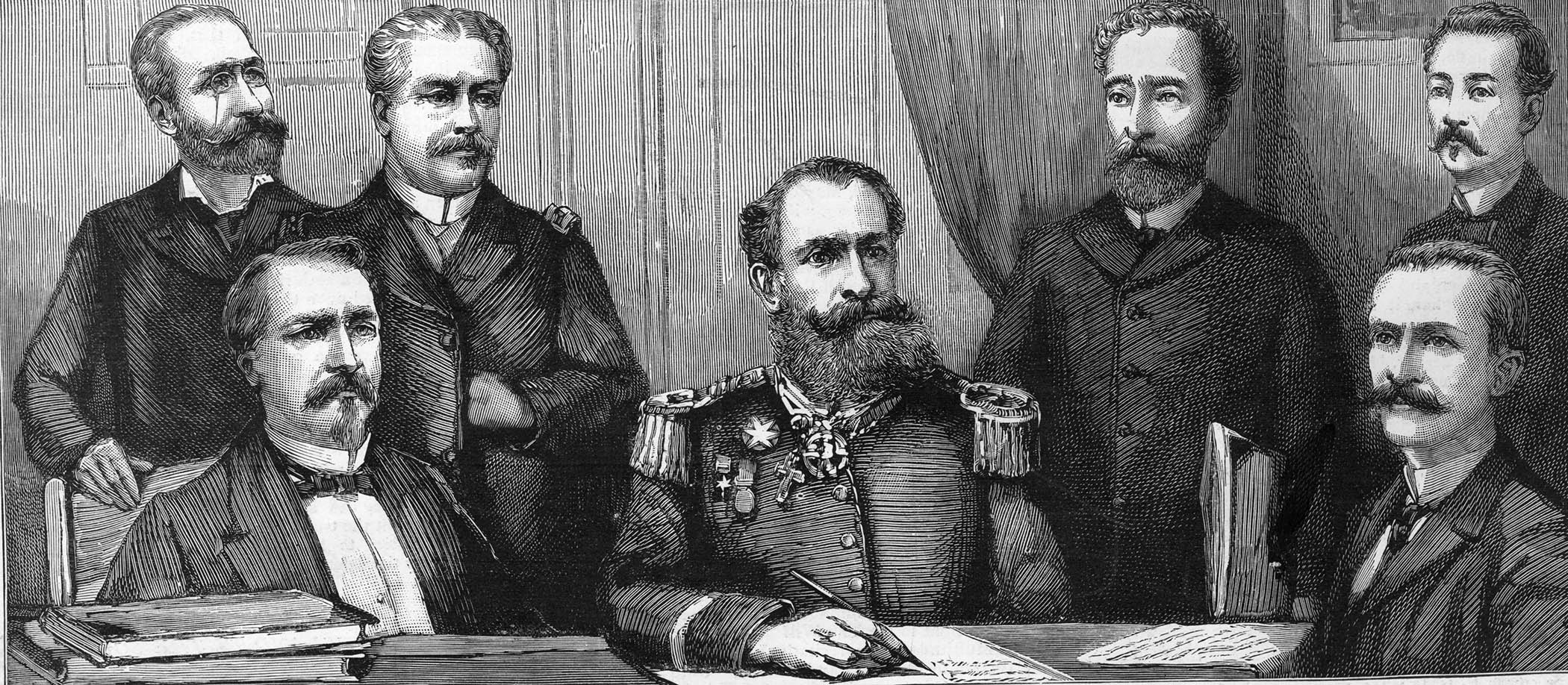

The first government of the Brazilian Republic, 1889

1889 – A military uprising topples the monarchy, and two marshals become Brazil’s president and vice-president.

1894 – Prudente de Morais wins Brazil’s first direct presidential election and becomes the first civilian in office.

1930 – A military junta deposes President Washington Luís and installs civilian Getúlio Vargas, who, by 1937, imposes a dictatorship that lasts until 1945.

1964 – The armed forces, backed by conservative elites and the US, depose President João Goulart, a left-leaning reformer, and begin a 21-year military regime.

1985-88 – The dictatorship ends with the indirect election of civilian Tancredo Neves, and the 1988 Constitution enshrines civil rights and military subordination to civilians.

2002 – Former union leader Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva wins the presidency, and is reelected in 2006. His appointee Dilma Rousseff follows with victories in 2010 and 2014.

2016 – Rousseff is impeached, accused of fiddling government accounts. Her vice-president, Michel Temer, takes office.

Jair Bolsonaro

2018 – Jair Bolsonaro, a former captain and backbencher congressman, wins the election.

2022 – Lula wins back the presidency, defeating Bolsonaro. Freed in 2019 after more than a year in prison, he returns to politics when his controversial corruption convictions are overturned.

2023 – Thousands of Bolsonaro supporters storm Congress, the supreme court and the presidential palace, demanding military intervention.

Photographs by Miguel Schincariol/Getty, Getty