You think it’s funny, when they tell you it’s called the Hill of Difficulty, but as soon as you begin to climb, the joke wears thin. A hundred yards in from the sign that says: “Welcome to Bounty Bay – Pitcairn Island – home of the descendants of the Bounty mutineers,” I’m breathless in the claustrophobic humidity of a late morning at the end of March.

We walk past a police station, a few low houses, their roofs gleaming darkly with solar panels, rainwater butts hooked to their gutters. I’ve grabbed a wooden walking stick from a plastic barrel by the quay and I’m glad of it as I haul myself up the incline.

We turn away from the island’s tiny, singular metropolis, Adamstown – where an anchor from the Bounty has pride of place in the town square – and begin the long, hot walk to St Paul’s Pool at the island’s eastern tip.

The walk is about four miles (just over 6km); the whole island is only about two miles wide and a mile long, but the path switchbacks and rakes steeply up or steeply down, with barely any level ground. My shoes are quickly coated with ochre earth that will stick to them long after I’ve left this place.

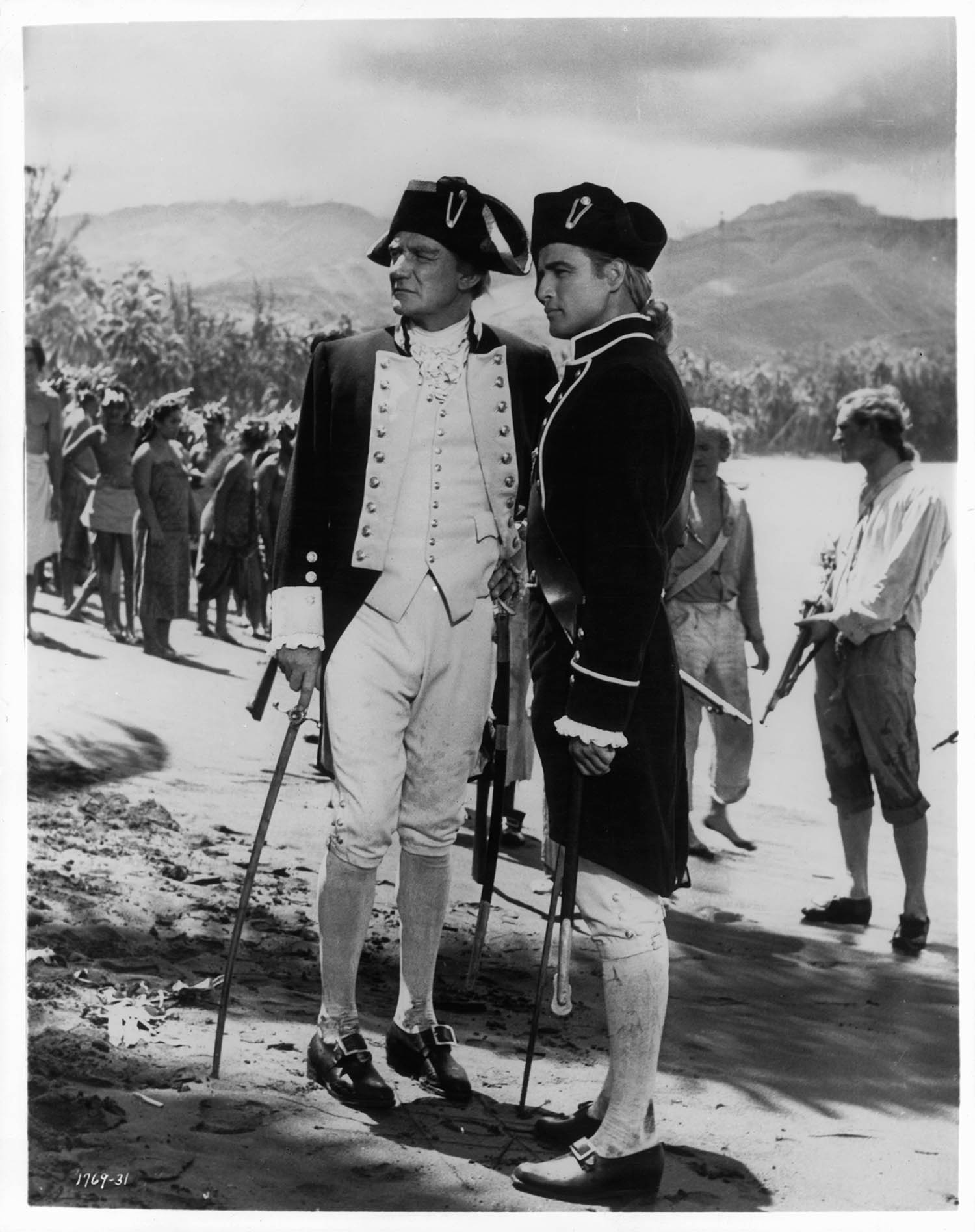

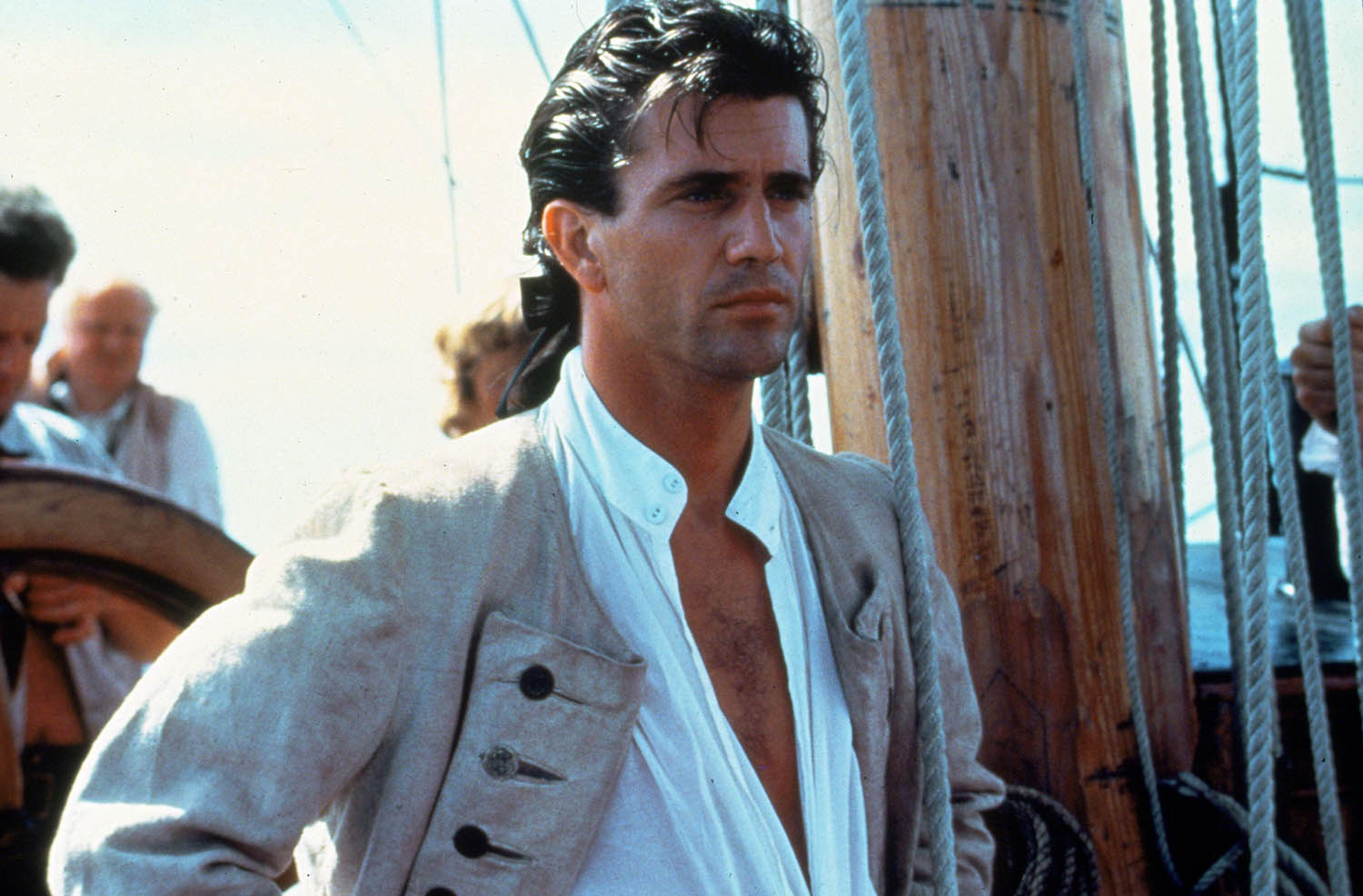

You know the story of the mutiny on the Bounty, if not in detail, at least in myth. You’ve seen Charles Laughton and Clark Gable, Trevor Howard and Marlon Brando, Anthony Hopkins and Mel Gibson. Maybe you know the mercenary, imperial origins of the mission that Captain William Bligh was on when he sailed for Tahiti in 1787. He was, as the website of the Royal Museums Greenwich states, on an expedition “to collect breadfruit to transport to the West Indies” – this was to be a source of cheap food for the enslaved labour there, but Greenwich leaves that out.

It was only in 1793 that the dogged Bligh finally got his plants to Kingston, Jamaica. At the end of April 1789, about 18 months after the ship had sailed away from Spithead, 18 of his men, led by master’s mate Fletcher Christian, mutinied and set Bligh and the loyalists adrift in the Bounty’s launch. Christian and co returned to Tahiti before eventually settling on Pitcairn, bringing with them their Tahitian “wives” – that is how they are often referred to, but how their consent can be understood remains unclear – and six Tahitian men, used as enslaved labour.

Marlon Brando, with Polynesian actor Tarita, as Fletcher Christian in the 1962 film Mutiny on the Bounty

To all intents and purposes, this whole crew disappeared off the face of the earth until an American whaler managed to land on Pitcairn in 1808 and the tale began to emerge. It was a murderous one, with the Polynesian prisoners finally rising up against their captors. In September 1793, several months after Bligh got his bloodstained botany to the Caribbean, Christian was killed.

The brutalised Tahitians fought among themselves and continued to fight their captors. Eventually, a kind of quietus emerged. As the official Pitcairn site has it: “The following four to five years were peaceful except for occasional outbreaks by the women, protesting against their treatment by the men, including an attempt to leave the island.”

Peaceful except for occasional outbreaks by the women.

I have wondered how history lodges in a place, ancient or human-made. On the ridge of Alderley Edge in Cheshire or the span of the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, it is possible to sense time as a living dimension, the past embodied in land, stone or even steel. Yet I would say that I know the Edge, I know the bridge. I was on Pitcairn (“Pitkern” is how the islanders say it) for perhaps six hours. That barely makes me a tourist, never mind someone who should express an opinion of a place. Yet like the dirt on my shoes, all these months on, it clings to me.

How do we imagine ourselves into landscapes and what they hold? When are we entitled to do so? I chose to come here because, well, I thought it would be an adventure; and, to be frank, I was offered a free trip. But I got more than I bargained for. My own past confronted me here in a way I never would have expected. We try to walk away from the shadows of our own histories: sometimes they will still cast themselves over us, even in brightest sunlight.

Our ship, the Pursuit, is anchored about a mile offshore. We’d set off nearly two weeks earlier from Santiago, Chile, and had already made landings at the Juan Fernández islands, at Rapa Nui – though most of our days were spent simply on the vast Pacific, no bird or bug in sight, thousands and thousands of metres of ocean below us. In the gym perched high above in the bow, every morning for a week on the voyage here, I had marched in place on an elliptical machine and lifted weights, and while I did so I listened to The Pitcairn Trials, a podcast made by a British journalist, Luke Jones.

Commemorative plaques

For the island’s tragic, damaged history is not all in the distant past. In 2004, six men were convicted of dozens of sexual offences; over four decades previously, systemic child sexual abuse had been rife in this seemingly Edenic place. A girl called Glenda, who grew up on Pitcairn, was sexually assaulted, raped, from the age of three; she described an island-wide complicity, a seeming acceptance – argued by some of the women associated with or even assaulted by the defendants in court – that this was “culture”, not violence.

In The Pitcairn Trials, she called back a memory of this time, when she was raped – as a toddler. “My body was rocking. Young as I was, I thought: ‘What’s going on?’ And there was this guy. Trying to. It wasn’t family. It was another guy on the island. I didn’t tell Mum and Dad but he came back the second night. And I screamed and I screamed and I screamed. Mum eventually came home, I was still crying, still upset. And they just said: ‘Go to sleep.’ So that was my first.” Glenda lives in the UK now, thousands of miles from Pitcairn.

A makeshift courtroom had to be constructed; those sent to the island to try the accused had to be brought ashore by those very same men in the Pitcairn Island longboat. (The accused and convicted would also build their own prison.) Jones’s forensic, atmospheric and sensitive documentary considers the island’s history and the culture of sexual predation that countenanced the repeated rapes of girls barely out of childhood. That was not quite the end of the story, either; in 2016, Michael Warren, a former mayor, was sentenced to 20 months in prison – to be served in New Zealand – after he was convicted of possessing more than 1,000 images and videos depicting child pornography. At the time, he had been working in child protection on the island.

There are 15 or 20 of us on this expedition to St Paul’s Pool. Simon Young, the mayor of Pitcairn, his damp ponytail a beacon of sorts, leads the way. Thick, green vegetation grows everywhere to left and right; I am incapable of recognising almost any of it, save for when a banana tree, comical in its obviousness, appears in view.

The heat is a wet weight. The place is shockingly beautiful. It is a rock in the middle of the ocean, like a child’s drawing of an island. At the base of the cliffs, the ocean is electric blue, deepening out to ultramarine and black as it stretches to the very rim of your gaze.

R and I have made this trip together. She lives in Los Angeles; I am a couple of oceans away, and we’re lucky when we get to spend time together. We have flown from our separate corners of the globe to find ourselves in this tiny, infinitely isolated place. As we tramp towards the pool, she is always just ahead of me: she is taller, fitter. But eventually we all arrive at the island’s tip, where the surf sweeps into a natural basin when the tide is out. If you plunge in at the wrong time, you’ll be swept out into the Pacific, simple as that; but we’ve hit the golden hour.

Trevor Howard and Brando filming the 1962 movie in Tahiti

A winding set of stairs bolted into the ground leads to a plateau above the pool; after that, it’s a scramble down over the remnants of a collapsed volcano. In a bathing suit and water shoes, R launches herself downward. I decide I’ve reached my limit of risk and exertion and keep watch from above. By the edge of the pool, one of our guides says to her: “Be aware, if you can’t get out by yourself, we can’t help you.” This is the kind of place Pitcairn is.

R and I separate again on the long walk back. It is as if this place wishes to keep us apart. I am exhausted. I am sure I have never been so hot. I want to leave here. It is so beautiful; sweat runs into my eyes and blurs the hot pink flowers, the viridian leaves.

At the edge of Adamstown there is shade and a place to sit by the shut general store; there are big jugs of cold water, so I refill my bottle and pour its contents over my head. This cools me down not at all. Souvenir stalls have been set up for us rare visitors. Wooden carvings, T-shirts, magnets, the usual stuff. Jars of honey, too; Pitcairn honey is a treasure, its population of bees is one of very few in the world entirely free from disease. When mayor Young had come on board the Pursuit earlier that morning to hand our captain a small wooden replica of the Bounty, he’d said that Pitcairn honey was sold at London’s most exclusive emporium, Fortnum & Mason – but it’s not, or at least, it’s not any more.

Pitcairn Island Pure Honey (Pipco Honey), I’d noticed, boasts a classy website – launched just last year – advertising its wares. “Discover the unspoiled splendour of Pitcairn Island” where “purity meets tradition”. On the site, under “Our team”, the manager smiles broadly beneath a richly fruited apple tree.

He is, or was, I realise, one of the six men convicted of rape and indecent assault in 2004. The case had in fact dated back to 1996, when a British missionary returned to London “with a complaint that his preteen daughter had been seduced by a Pitcairn man”, as the New York Times phrased it in 2004. The missionary asked the police to investigate. Preteen, seduced: language purporting to be condemnatory aligning itself unthinkingly with violence and corruption. The Bounty mutineers “seduced” the women of Tahiti, or were, it is claimed, “seduced” by those women.

A couple of months after I leave the island, I have a video call with mayor Young. We never got to speak when I was ashore, but I was powerfully struck by his pride in the place and his love for it. I’m back home in east London; when we log on, he picks up his computer to show me the gleaming view from his house high on the island’s bluffs.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Elected in 2022, he is the island’s first non-native mayor; it’s Yorkshire that he calls home, though he says he grew up all over the place. His father was in the RAF and eventually he joined up too. But once he was discharged, he studied horticulture and his journey towards Pitcairn began. “I was always drawn to smaller, isolated places,” he says. “I don’t know why. I’ve got one sibling and she’s completely the opposite – she hasn’t even been to Pitcairn and she’s got a good reason to come. It’s just not her cup of tea.”

He first visited the island in 1992; his first stay was six months long. “People may still think of us as isolated, and I suppose we are, but in comparison to how it was, this is nothing.” On that initial visit, the only communication was shortwave radio to New Zealand; he only spoke to his mum once.

He speaks of the sense of responsibility he feels to the island and its tiny population – fewer than 50 people these days, many of them still claiming descent from those original settlers.

“Not to put any pressure on you, Erica,” he says, “or on what you mean to write, but I think you have a responsibility. The story you tell has an impact on Pitcairn. If it’s only focused on the trials of the past, then all it does is regurgitate bad press for Pitcairn Island, which is never a good thing. It doesn’t help the island, it doesn’t help me. It doesn’t help that community.”

We observe each other from thousands of miles away, Elon Musk’s Starlink enabling our exchange. “You have to do what you think is right, Erica, but I just throw that in there.”

Do what you think is right. What is that? And “right” by whom? How do we balance our obligations to the past with our hopes for the future? I was “seduced” when I was 14 years old; and like many of those on Pitcairn, it happened with the complicity – a challenging word – of someone who should have kept me safe. Where were the mothers, someone asked me when I was discussing this story? I might also have asked myself: where was mine?

I do not compare my experience to the generations of systemic abuse suffered by the girls and young women on Pitcairn Island. But I recall it, and it lives inside of me. On Pitcairn, the bees make the honey; the islanders harvest it. The trials, Young tells me, “fragmented the community, and it took many years for that to heal”. It was a decade and a half “before people had compartmentalised and processed correctly what had happened, and for safeguards to be put in place so that it could never happen again”.

Mel Gibson as Fletcher Christian in 1984’s The Bounty

At one of the little stalls, I bought a jar of honey. The man who sold it to me was friendly; he was in his sixties, I suppose. I didn’t ask his name. I didn’t go into Adamstown to see the tourist office, the Bounty anchor. With my honey in my rucksack, I stumbled down the hill towards the dock. R was already there, waiting for me. My legs were shaking: I had to sit down.

Young is up for re-election in November. He got in by a narrow squeak last time and can’t speak to his political future, only to the fact that he knows he belongs on Pitcairn. I liked him, and I wish him well; his hope is to draw migrants to the island so that it may be repopulated. As the “immigration” page on the islands website has it: “The community is aware of the urgent need to grow in order to sustain itself and ensure a viable future.” Young tells me of an American couple who will be moving there later this year with their 17-year-old son. I find myself wondering if they are preppers, a family determined to wait out the apocalypse in what they imagine is safety, but in the face of Young’s optimism, it seems rude to ask. There are no school-age children currently on Pitcairn.

All these months have passed and I cannot get away from Pitcairn. I’ve opened my jar of honey; it’s rich, complex, deeply floral and dark. I close my eyes see the island. The ochre track, the vibrancy of colour, the lush vegetation – all say “paradise”, “paradise”, “paradise”, but tramping along the island’s stony spine, I felt so claustrophobic I thought my heart might actually stop.

Back in the 1830s, Charles Babbage, early pioneer of what we now call computing, proposed a theory that each breath, each word, left traces all around us: “The air itself is one vast library on whose pages are for ever written all that man has ever said or woman whispered,” he wrote.

Is there anywhere that does not carry the depredations of its history? Everywhere is terrible, in the end. Yet Pitcairn, more clearly than any place I’ve ever been, seemed to speak its past. Those mutineers, brutalised themselves by the greed and violence of their era, patterning their society as best they could. Their descendants wishing to remake the world but still bound by the cruelties of centuries.

I feel the call of my own past, an old violent wound I’ve learned to live with but that finds its echo here. The brutality of what has gone before makes us: we have no choice but to find the beauty in it. I know this place. It knows me.

Photographs by Alamy, Getty Images