Marching through the streets of Dahiyeh in southern Beirut, men beat their chests and chanted slogans. They carried Hezbollah flags, the infamous green AK-47 emblem hovering over Arabic script reading “Party of God”, passing one pancaked building after another. Children darted between the crowds, some wearing yellow Hezbollah headbands, clutching lemonade bottles adorned with the face of the late Hezbollah secretary general, Hassan Nasrallah.

They were marching to commemorate Ashura, a day of mourning for Shia Muslims held annually to commemorate the death of Husayn ibn Ali, grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, killed in AD680 at the battle of Karbala.

But it also served as a show of support for Hezbollah, which needs all the backing it can get after its devastating war with Israel last year left it decimated – its leaders assassinated, thousands of its soldiers killed and its influence inside Lebanon damaged.

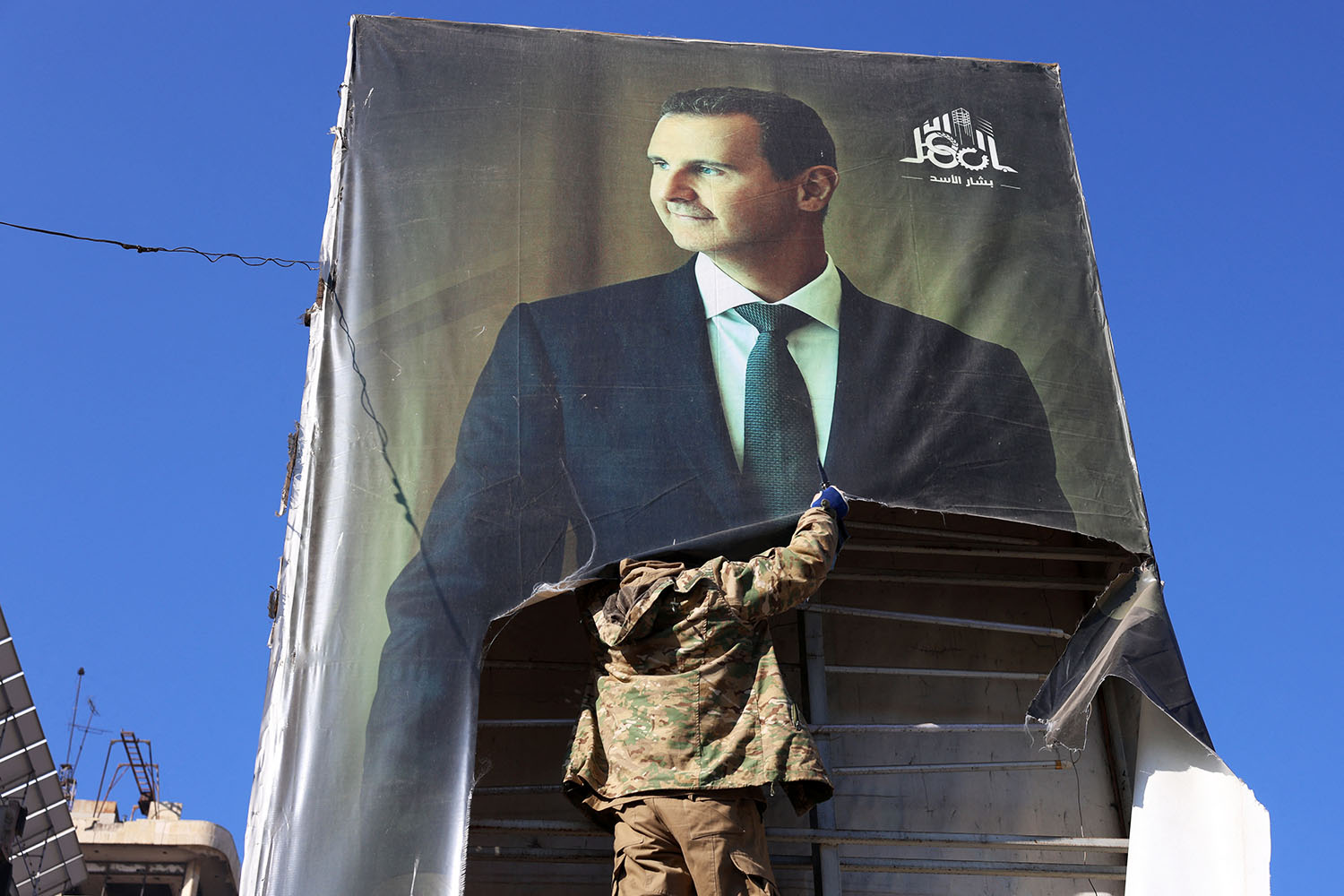

Further setbacks followed. In neighbouring Syria, the regime of Bashar al-Assad collapsed in December after nearly 14 years of civil war. Hezbollah forces – long stationed in Syria to prop up Assad – withdrew overnight, abandoning both the Assad family and its key supply route from Iran to Lebanon.

‘Hezbollah as a military organisation is a thing of the past. Now it has to face the moment of truth’

‘Hezbollah as a military organisation is a thing of the past. Now it has to face the moment of truth’

Dr Hilal Khashan, American University of Beirut

Next, Israel launched a blistering 12-day war on Iran that left Hezbollah’s key patron unable to send funds to Lebanon as it surveyed the destruction at home.

Weakened and isolated, Hezbollah now faces disarmament talks. A US proposal offers reconstruction aid and a cash injection into Lebanon’s failing economy, a halt to daily attacks by the Israeli military, their withdrawal from Lebanese territory and the release of Lebanese prisoners. In exchange, Hezbollah must lay down its arms.

Hezbollah now faces the most significant choice in its 40-year history: to disarm, fight on or turn fully to politics.

“Hezbollah as a military organisation is a thing of the past,” said Dr Hilal Khashan, professor of political science at the American University of Beirut. “Now they have to face the moment of truth. The Israelis, the Americans and Muslim groups want Hezbollah to be disarmed.”

Related articles:

For some in Hezbollah, disarmament is an existential threat, and the group is certainly not a thing of the past.

Ali, a 39-year-old mechanic and Hezbollah fighter, tried to strike a defiant tone. “They might be damaged, but they are not finished,” he told The Observer. “Why would Hezbollah give up their weapons while we have Israel killing civilians left and right without any international organisation trying to stop them? I know that Hezbollah won’t give up the important weapons.”

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Ali’s anger gave way to grief. “I have been feeling depressed, honestly. We lost a lot of good people, especially Sayed Hassan [Nasrallah],” he said. “It was hard on all of us. Every one of us lost someone in this war. I lost a lot of my friends and neighbours. I also lost family members and property – but that is a price I’m willing to pay.”

So was it worth it? “We did our Islamic duty. We might not have anticipated this amount of barbarism from the Israelis, but I think it was worth it. History will remember that we the few tried to stop a genocide funded by the west.”

Still, Hezbollah’s role is fiercely contested. It is described as a state within a state, and the power of its military wing has long eclipsed Lebanon’s official army. Critics say it has blocked crucial reforms needed for international aid, using its power to maintain influence while Lebanon crumbles.

Naim Qassem, Hezbollah’s current secretary general, addressed the issue via video screens to those gathered at Ashura. “We cannot be asked to soften our stance or lay down arms while Israeli aggression continues,” he said.

Khashan believes Qassem’s message is deliberately defiant toward Israel, but with subtle flexibility. “This does not exclude Hezbollah’s willingness to surrender its arms to the Lebanese army … In this region, face-saving is important.”

On the ground, the atmosphere remains tense. Hezbollah’s base has paid a heavy price: loved ones lost, homes destroyed, livelihoods shattered. Its popularity still draws heavily from its extensive social infrastructure: schools, hospitals, ambulances, and heavily subsidised food markets. But reconstruction is urgently needed, and Iran – long its patron – is now consumed with its own recovery.

Marines search for survivors after a suicide car bomb was driven into their barracks headquarters in Beirut, killing 241 and wounding more than 60

Analysts believe Hezbollah’s future may lie increasingly in politics. Much like Sinn Féin after the Good Friday agreement, it could shift its focus to Lebanon’s parliament.

“Hezbollah wants a dignified arrangement that gives people the impression they are still around,” said Khashan. “Since the end of the war, Hezbollah has been talking regularly about close coordination with the Lebanese army.”

This, he says, could lay the groundwork for Hezbollah’s military wing to merge into the national forces – quietly and symbolically, without ever uttering the word surrender.

Back on the streets of Dahiyeh, surrounded by defiant Hezbollah supporters kicking up the dust of destroyed buildings as they pressed on through the heat, Ibrahim Issa, a 50-year-old architect, took a moment to reflect as he watched the parade from a pile of rubble, his 14-year-old son beside him.

Hezbollah’s weapons “are our shield, our protector, especially as Israel is still hitting us,” he said. “In return for weapons, you would need peace and a strong army to protect us, or we will be naked. It would be suicide.” At that moment Qassem’s voice floated over from a loudspeaker, causing Issa to turn once again to his son with a look of pride.

“If we die, we win – and if we win, we win,” Qassem shouted, addressing Israel directly. “Don’t test us.”

A history of Hezbollah

1982 Founding

Hezbollah emerged during Lebanon’s civil war, inspired by Iran’s Islamic revolution and supported by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards. It positioned itself as a resistance force against Israel’s occupation of southern Lebanon after the 1982 invasion. A year later, a truck bomb destroyed the US Marine barracks in Beirut, killing 241 American servicemen. The attack, claimed by a group called Islamic Jihad – later linked to Hezbollah – brought the organisation to global attention and made it a target for the US.

After the 1989 Taif agreement ended the civil war, Hezbollah was the only militia allowed to retain its arms. It positioned itself as a legitimate resistance group rather than a militia.

1992 Politics

Hezbollah entered Lebanese politics, alarming some supporters who feared it would become moderate. The group insisted it could pursue both political engagement and armed resistance. This dual strategy marked the start of Hezbollah’s rise as both a military and political power.

2000 End of Israeli occupation

After years fighting against Hezbollah’s guerrilla warfare, Israel withdrew from southern Lebanon.

Hezbollah claimed victory, gaining admiration across the Arab world as the first group to force out Israel militarily.

While this bolstered its domestic and regional standing, it also set the stage for future confrontations with its neighbour.

2005 Assassination of former Lebanese PM Rafic Hariri

Hariri was part of the anti-Assad opposition in Lebanon when Syria occupied part of the country. This event turned public opinion against the group and strained its image. Later four Hezbollah members were indicted and one, Salim Ayyash, was convicted.

2006 War with Israel

Hezbollah triggered a war by kidnapping two Israeli soldiers after Israel refused to release Lebanese political prisoners. The conflict lasted 34 days, killing more than 1,000 Lebanese civilians and dozens of Israelis, and leaving Lebanese infrastructure in ruins. Hezbollah’s rocket attacks on northern Israel and its resilience in the war earned it renewed regional prestige but also deepened domestic divisions and led to the UN resolution 1701 calling for on the disarmament of militias in southern Lebanon.

2012-17 Syria

Hezbollah intervened in the Syrian civil war in support of its ally, President Bashar al-Assad.

While the move was controversial at home – many accused the group of dragging Lebanon into a foreign conflict – it significantly expanded Hezbollah’s military capabilities and influence.

A permanent land bridge was established between Iran and Hezbollah.

The intervention elevated it from a local resistance group to a key player in Iran’s regional strategy.

2023–24 Gaza war and the fall of Assad

After Hamas’s 7 October attack on Israel, Hezbollah opened a northern front in support by firing rockets from Lebanon. Expecting a repeat of 2006, Hezbollah was unprepared for Israel’s advanced intelligence and military response. Targeted airstrikes destroyed much of its infrastructure, and leader Hassan Nasrallah was killed in a bunker-busting raid in September 2024.

Two months later, Assad’s regime fell, cutting Hezbollah’s supply lines. With Iran reeling from its war with Israel and internal crises, Hezbollah found itself isolated.

For the first time, its disarmament became a real possibility, and its future as a dominant force in Lebanon and the region was cast into doubt.

Photographs by Oliver Marsden, Peter Charlesworth/LightRocket via Getty and Mohammed al-Rifai/AFP