Ten years ago Elon Musk’s first biographer described in riveting detail how Musk took on the most successful agency in the history of the US federal government – Nasa – and made it look bloated and feckless.

Nasa had been used to paying $10 million and waiting years for a new set of computer systems for a rocket, Ashlee Vance wrote. Musk’s SpaceX set out to build one in weeks with off-the-shelf components for $10,000, and – give or take – it succeeded. It also built a functioning space capsule, the Dragon, for $300 million, which was “10 to 30 times less than capsule projects built [for Nasa] by other companies”.

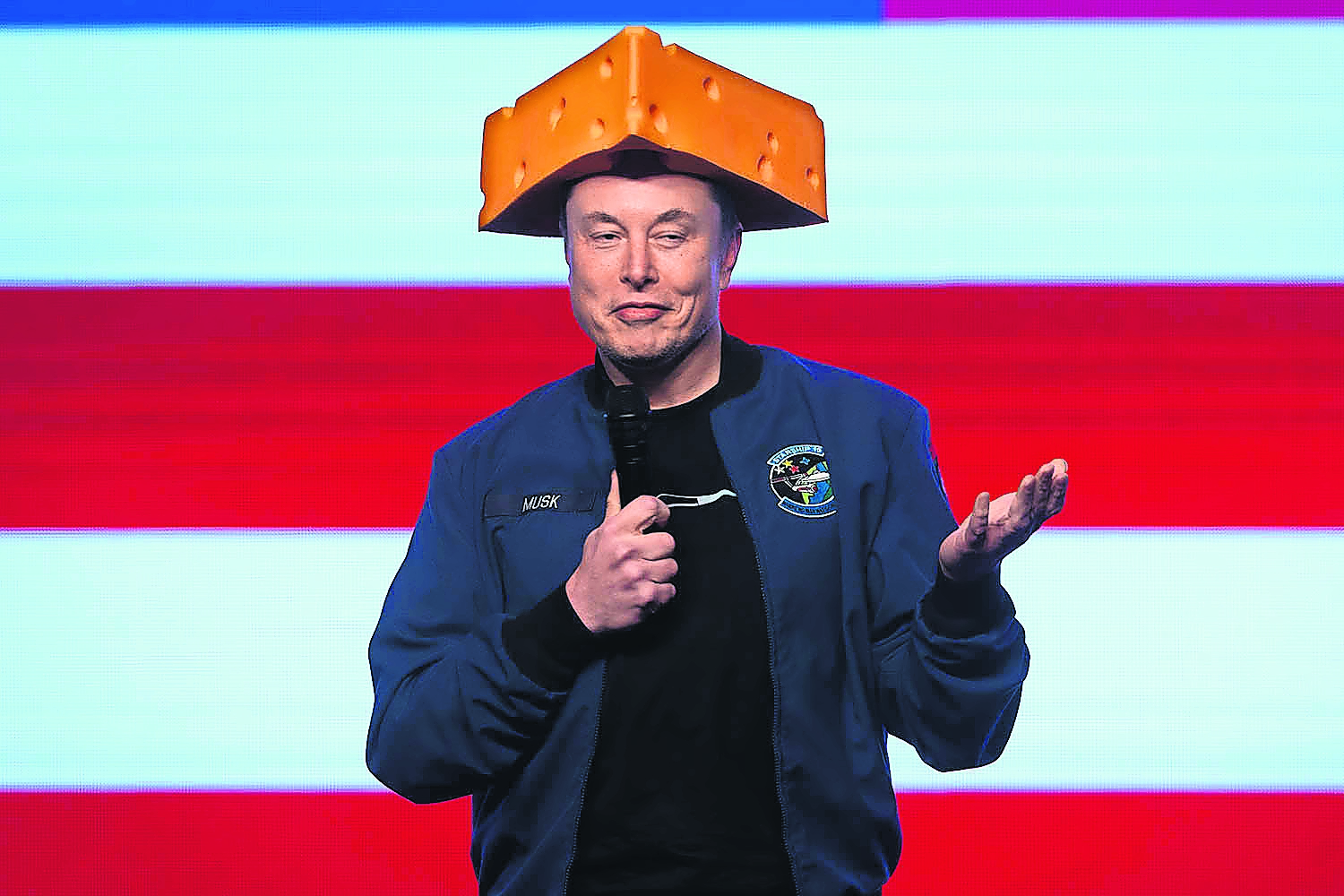

It was surely a no-brainer that if anyone could take a chainsaw to the federal bureaucracy writ large, it was Musk. In January he got his chance. On Friday, 130 days later, he bowed out in a press conference in the Oval Office, his reputation torn to shreds, with enemies wherever he looked in business and politics and an actual black eye.

Musk stepping down at the White House – and sporting the black eye he said his son gave him while they were ‘horsing around’

It seemed appropriate that he blamed the shiner, however implausibly, on a punch to the face from his five-year-old son. Two days earlier, the New York Times had described how people close to Musk had watched him mix work with routine drug abuse – ketamine, ecstasy, magic mushrooms and the addictive stimulant Adderall. The paper’s sources saw in that behaviour an explanation but not an excuse for a maniacal assault on American foreign aid and public service that has cost tens of thousands of livelihoods in the US and the lives of vulnerable people abroad who had depended on US-funded drugs.

What was going on? The world’s richest man was “killing the world’s poorest children”, said Bill Gates, the Microsoft founder.

What else? The world’s richest man was manipulating a biddable president into supporting federal funding for a trip to Mars. He was testing to destruction the notion – perennially popular on the American right – that business knows best. And there is now mounting evidence that he was personally unravelling on the world stage from exhaustion, overstimulation and an overdose of hubris.

Former staff tell a story of deep disappointment. ‘I saw Anakin turn into Vader,’ says one

Former staff tell a story of deep disappointment. ‘I saw Anakin turn into Vader,’ says one

The low points in Musk’s extended dance though geopolitics have pulsed into the ether like distress signals, but mainly for the distress they have caused others. In January, two weeks before Donald Trump’s inauguration, he posted on X that “only the AfD can save Germany”.

Wading into German politics on behalf of the far-right Alternativ für Deutschland prompted a 60% slump in Tesla sales there but did not disqualify him from leadership of the US Department of Government Efficiency. Far from it – he was a guest of honour at the inauguration. Afterwards he performed a Nazi salute celebrated in parts of Magaworld but condemned almost everywhere else, including on the floor of the European Parliament.

Related articles:

Days later Musk made the first of several bizarre appearances in the Oval Office with his son, X, one of 14 children he’s known to have fathered. It was a masterclass in how to drag the personal into the public sphere. Musk will now face questions not only about his drug use as head of a federal contractor (SpaceX), but about his rapidly extending family.

He stands accused by X’s mother, the artist known as Grimes, of violating a custody agreement drawn up to protect the child’s privacy. It’s now also publicly reported that he offered the mother of his 14th child, the writer Ashley St Clair, $15 million and $100,000 a month to keep his paternity secret; that she turned him down; and that according to St Claire he said he would be willing to offer his sperm to anyone who wanted it.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Was this business maverick brought into the heart of American government psychologically unstable? Before he entered politics, admirers would often wonder how he found time in the day to run four major companies (Tesla, SpaceX, X and the Starlink satellite communications network) while allegedly staying up much of the night to play video games.

How did he find the headspace and the inclination to meddle in the domestic politics of Germany, and Spain, where he has spoken out in support of the heirs of General Franco, and the UK – where he has been an online champion of the anti-immigration extremist Tommy Robinson?

Musk with his son, X Æ A-12, and President Trump in the Oval Office

One country on which Musk claims expertise is South Africa, where he was born. Last month he was the ghost at the party when President Ramaphosa arrived at the White House to reset relations with the US. Trump tried to turn the meeting into an ambush based on false claims of a genocide of Afrikaners to whom he had offered asylum. The president said Musk didn’t want this to be “about him”. But of course it was.

For six months, at a cost of $250 million of his own money, Musk bought the role not just of unelected slasher of the federal government but of Trump-whisperer-in-chief. He fed the world’s most powerful man false narratives of South African history just as he had fed him wild claims of his ability to shrink the state.

He set out to save the US treasury $2 trillion, walked that back to $1 trillion and now claims to have found cuts worth $175 billion. Other estimates range from $80 billion to an extra $135 billion in costs to the taxpayer from the upheaval caused by Doge.

In his early days as an electric car pioneer Musk was considered by his staff a progressive and a friend to Democrats. “People believed we were accelerating the world’s transition to sustainable energy,” says Kristen Kavanaugh, a former diversity manager at Tesla who felt no resistance from Musk at first towards her efforts to cast the company’s hiring net wide. “That is typically a progressive value and a progressive view of the world.”

There was a rational if not ethical case for cosying up to the man in the red cap and his America First agenda. Tesla sales depended to a considerable extent on federal rebates for electric cars. SpaceX depended to an even greater extent on federal contracts, including one to provide a lunar lander for Nasa’s next moonshot.

Musk in Wisconsin during a rally where he gave out two $1m cheques

There was also every reason to assume Trump would keep his efficiency tsar in post beyond the 130 days allowed as a special government employee if his work was useful to the administration. It was not. Not only has Doge made minimal savings, if any. It has driven the rest of Trump’s cabinet to something close to despair. Musk called Peter Navarro, until recently Trump’s leading China hawk, a moron. Then he had a shouting match in the West Wing with Scott Bessent, the treasury secretary. It’s said they squared up to each other like prize fighters, and spittle flew.

If Musk’s businesses had been thriving in his absence he might have asked to be kept on in the White House and in Mar-a-Lago, where he rented a cottage soon after the election. But they weren’t. Tesla lost $400 billion in market value in two weeks shortly before Christmas. It reported a 71 per cent fall in profits in the first quarter of this year, and catastrophic declines in sales across Europe.

Former staff tell a story of deep disappointment. “I saw Anakin turn into Vader,” Kavanaugh says. It was a return-to-work order issued by Musk at the end of lockdown that did it for her. Employees who wanted to continue to work from home should consider themselves fired, Musk said. “I got the people out that wanted to get out and then I walked the next day,” says Kavanaugh.

Tesla’s rivals are catching up and its investors are anxious. Last week, several pension funds with big stakes wrote a letter demanding a succession plan. Musk has said he will spend more time at the company but the funds are not convinced.

They know his true passion is space, and getting to Mars. Weeks before the US election that quest looked on a roll. Two giant “chopsticks” caught Musk’s biggest spacecraft, the Starship, as it fell to earth in Texas, proving it could be reused. But three test flights since then have blown up.

On Friday in the White House Musk looked exhausted. Challenged on the New York Times report, he attempted to trash the paper and told the reporter to “move on”. It will be tempting now for his legions of critics to count him out. He is certainly on his way out of Washington, where few will mourn his departure. And his chaotic personal life may yet drag his gravity-defying businesses back to earth.

But this is Musk. There is madness in his methods but the reverse may be true too. Professional Tesla watchers accuse him of three big strategic errors: failing to bring a truly affordable electric car to market, betting on a doomed pickup truck instead, and diverting investment to robotaxis and humanoid robots that don’t yet exist. But so far Wall Street has kept the faith – not with the bruised political Musk but with the wild visionary of tech.

At SpaceX the stakes are even higher. With Musk whispering in his ear, Trump has announced plans for a Golden Dome missile defence system, which will depend critically on SpaceX rockets and Starlink satellites. “Lasers from space,” Musk tweeted without explanation not long ago. On the road and on the launchpad he has been able to see round corners when rivals have looked only straight ahead. It’s too soon to say he’s lost the knack.

Photographs by Andrew Harnik/Getty; Allison Robbert/AFP via Getty; Jim Watson/AF; Scott Olson/Getty