I am a librarian. I am fortunate enough to run one of the world’s largest and best known libraries – the Bodleian in Oxford – but my experience of libraries began as a reader. My mother took me as a child to the Deal public library in Kent, and it was there, in its modest book-filled rooms, that I discovered new worlds. My life was transformed by a public library (and its librarians) that allowed me to read freely from its well-stocked shelves. Throughout my career, I have seen at first-hand how libraries underpin the education and self-improvement of all of our citizens, rich and poor, young and old, of all creeds and colours, through providing access to a multitude of ideas and knowledge.

They celebrate the history and identity of our communities; they are stout defenders of facts and truth in an age of misinformation; and they are places where people can learn about their rights and how to protect them. This year we celebrate the 175th anniversary of the Public Libraries Act of 1850, which created our system of free public libraries – a kind of “NHS for the mind”. But what has been happening to American libraries rings a loud alarm bell for our own cherished library system.

Libraries large and small in the US are now on the frontline of the battles over knowledge that have intensified since the second presidency of Donald Trump began. The attack on libraries and librarians there is shocking and happening at a disorienting pace. Thousands of books have been banned from public and school libraries, librarians have received death threats and many have been fired. The heads of both the National Archives and the Library of Congress have been sacked on spurious grounds. Data has been deleted and funding for critical initiatives ceased.

Why is the US, the land of the free, where the realm of ideas and knowledge has been enabled by the first amendment, now turning on institutions that have been among the most trusted in society?

The first dispatches from the war on libraries began to reach me in 2022. I had recently published Burning the Books, which highlighted the role of libraries in society through a long history of attacks on the written word. Librarians began to send me messages and tagged me on social media, sharing news of assaults on public and school libraries in Florida and Texas. As one librarian put it, my book was fast beginning to look as if it would need updating. A pattern was forming: an epidemic of book banning, driven by groups from the far right of the political spectrum, empowered through social media, and funded, it seemed, by larger and darker organisations.

Throughout Joe Biden’s presidency, a coalition of extremist groups, with interests ranging from Christian nationalism to white supremacy, and anti-gay protesters were able to mobilise around common themes such as opposing sex education, LGBTQ+ issues and race equality. They began a concerted campaign to control what young people could read. Two tactics were deployed. The first was to seize control of the boards that oversee small public and school libraries. The boards then censored the books available to library users, especially young people. The second was the mobilisation of supporters using social media, manufacturing outrage through spreading lies, and encouraging challenges to libraries and attacks on librarians.

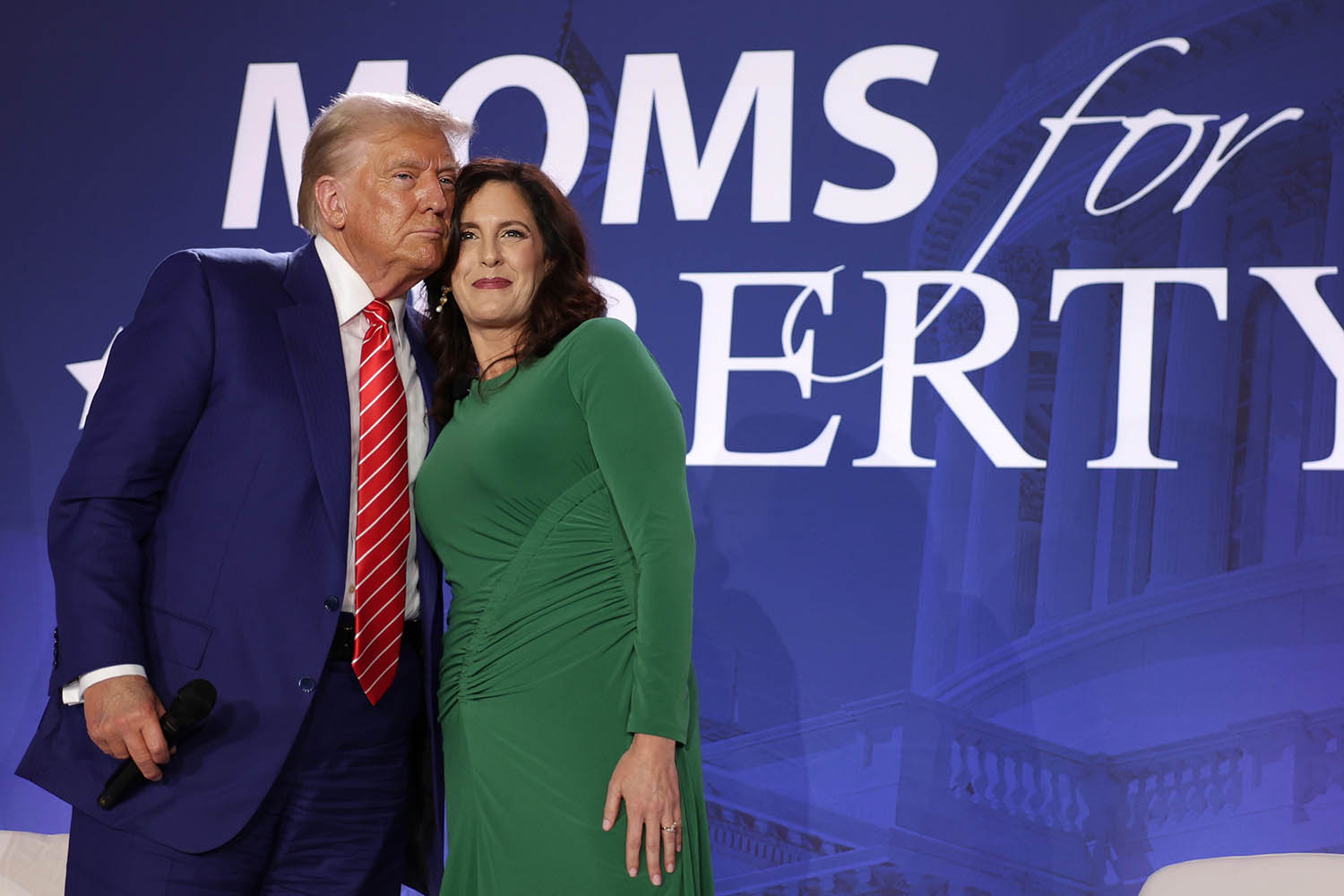

Donald Trump with Tiffany Justice, founder of Moms for Liberty in 2024

These tactics have been highly successful. The American Library Association (ALA) collects data on book bans in US libraries. Between 2001 and 2020 an average of 273 unique titles were challenged each year. In 2023, 9,021 individual titles were challenged across hundreds of libraries.

In March 2023, I was in New Orleans speaking at the Tulane book festival. My talk drew a much larger crowd than I had expected, including many librarians from across Louisiana who had been victims of book banning and personal attacks. Some of them spoke with me afterwards, revealing the pressure they were facing.

It was here that I first heard about Amanda Jones, a school librarian who had spoken out against book banning at a meeting of the Livingston parish library’s board of control meeting in July 2022. Jones instantly became a target for the hateful ideology aimed at libraries in the US. In her defence of libraries holding books on topics such as same-sex relationships, she was falsely accused of grooming children for paedophilia, and of advocating teaching “anal sex to 11-year-olds”. The online threats against her became so terrifying that she bought a Taser and pepper spray, and slept with a shotgun under her bed.

“The current wave of book banning sweeping the country has created a chilling effect on our education system and the purchasing of books in our libraries,” Jones wrote in her book That Librarian. “This is a huge movement that has been in the works for a while. It is well funded and well coordinated. It is about marginalising and erasing cultures and groups of people; it is about defunding public institutions; it is about dumbing down society for a more easily led population; and it is about using libraries for political gain.”

I spoke with Jones last month and asked her whether the threats were abating? She still sleeps with the shotgun, she said. Jones is a naturally warm and open person, cheerful, kind and intelligent: just the sort of person you would want running a school library. The personal threats she has received have only made her more resilient and more determined. She remains positive. She likens the epidemic of book banning to “a cancer that has spread. Some states are in remission while others have just been diagnosed.”

Her strength has been an inspiration. Many other library workers – often poorly paid and overworked – have stood up to the bullies, putting themselves and their families at risk to defend their libraries: Martha Hickson from Annandale, New Jersey, Suzette Baker from Llano County, Texas, and Audrey Wilson-Youngblood from Tarrant County, Texas, are some of the leading warrior-librarians. None expected to become soldiers for freedom of expression.

Jonathan Friedman is the Sy Syms managing director of US free expression programmes at PEN America, an organisation that defends writers’ right to free speech, and is a natural ally of librarians. (I worked very closely with PEN when I organised Oxford Reads for Rushdie, an event where writers read from Salman Rushdie’s works after the assault on the author that saw him lose an eye.) Friedman has been deeply immersed in the fight against book banning for the last four years.

He told me recently that “pressure groups were spurring local resentment through social media and online webinars, using that to stir up local volunteers”. These groups, such as the conservative 1776 Project and especially Moms for Liberty, have funded many candidates to stand for election to school and public library boards. Moms for Liberty, an organisation with more than 300 chapters, describes its members as “joyful warriors on the frontlines” but focused on “fighting for the survival of America by unifying, educating, and empowering parents to defend their parental rights at all levels of government”.

Dr Carla Hayden, pictured in the Library of Congress’s Jefferson Building

It is connected to extremist groups that expound conspiracy theories, such as QAnon and the Proud Boys, and to political action committees that channel funds to rightwing causes. Enrique Tarrio, leader of the Proud Boys, has boasted that Moms for Liberty is “the Gestapo with vaginas”.

What is clear to Friedman is that although some groups such as Moms for Liberty will claim that they are campaigners for “parental rights” or “freedoms”, their goal is to control and limit what young people can read, and the ideas they can encounter. According to John Szabo, director of the Los Angeles Public Library, up until a few years ago, intellectual freedom “was a quaint topic of conversation that only occasionally resulted in a challenge”. Now such challenges are “happening everywhere, even in southern California … and at McCarthy-era levels”.

Which books are in the firing line? Invariably, anything to do with sex. One group in Tennessee sought to ban a book about seahorses as it contained images of them mating. Books on the broad themes of LGBTQ+ continue to be a target, making up 39% of challenged titles in 2024. One, Uncle Bobby’s Wedding by Sarah Brannen, is a children’s book in which the favourite uncle of a young girl gets married. The uncle happens to marry another man. The book has been a target for banning in Colorado, Nebraska, Missouri, Florida and Maryland, and although many of those attempts have failed, some remain the subject of court cases.

The book banners also target the key texts of racial literature in the US. Maya Angelou and Alice Walker are well represented on the lists hosted by sites used to encourage book banning, such as Book Looks (which was taken down in March this year, claiming that its work, ordained by God, was “complete”). A school board in Tennessee banned the landmark graphic novel Maus by Art Spiegelman, which shows the horrors of the Holocaust.

Trump’s second presidency has heralded a more ferocious phase in the book-banning wars, moving these acts of local censorship to state and federal level. In April, I received an email letting me know that the Rutherford County’s board of education in Tennessee ordered 145 books to be removed from circulation, citing their “sexually explicit” content; they included Beloved by Toni Morrison and Forever by Judy Blume. In May, a judge ruled that users of Llano County library in Texas have no first amendment right to receive information in the form of books held by public libraries, and that the choice of books a library holds is a form of allowable “government speech” immune from constitutional scrutiny. At a stroke, in Trump’s US, public libraries are the mouthpiece of central government.

In June, empowered by this decision, the Florida state board of education ordered the removal of another 55 books from circulation. Meanwhile, in the case of Mahmoud v Taylor, a group of parents in Montgomery County, Maryland, have claimed a first amendment right to opt their children out of being taught titles including Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, taking their case to the supreme court. On 27 June the court ruled in their favour, limiting access to LGBTQ+ books. “Free people read freely” proclaims a T-shirt I was sent by colleagues at the ALA. Not in Trump’s America.

The great civic public libraries, such as those in New York, Brooklyn, San Diego, Boston and Los Angeles, have not sat idly by as the smaller libraries drew the fire. They have digitised banned books to make them available freely online and they have helped develop toolkits to support libraries facing book banning. Despite these efforts, Friedman’s assessment of the future of the free circulation of ideas in the US is sobering: “Between Llano County and Mahmoud v Taylor, we are now seeing a radical upheaval in the legal frameworks for freedom to read,” he explained. It is hard to believe, but in Tennessee, the works of Bill Watterson, the cartoonist author of Calvin and Hobbes, are now considered a danger to young people and are banned in school libraries in many counties.

One group is trying to ban a book about seahorses because it includes pictures of them mating

One group is trying to ban a book about seahorses because it includes pictures of them mating

In late April, I received a message from Sebastian Majstorovic, a digital historian in Germany. He had read a piece I had co-written with Nanna Bonde Thylstrup in the New York Times under the headline: “Politicians shouldn’t get to delete inconvenient facts”, which highlighted the rapid removal of vital data from government websites, especially in the areas of public health, disease control and environmental monitoring. Majstorovic asked if we could speak. Our call showed how strong the imperative to preserve remains in library-land. Majstorovic works with a group of volunteer librarians called the Data Rescue Project. They have worked with insiders in the US government in the last few months to save more than 1,000 datasets that had been deleted from government websites. He is clear about the threat. “What is happening in the US,” he told me, “can be described as a digital book burning.”

They now need established institutions to host the rescued data sets. The Max Planck Institutes in Germany have already taken on huge amounts of environmental data, but other homes are needed. The head of Research Libraries UK called to let me know of a US university library that needed to move a digitised resource outside the country in case it was targeted for deletion. A UK library is now going to give it safe harbour.

In February 2025 I checked my email late one night. Even after all these outrages, I could hardly believe what I read. Dr Colleen Shogan, 11th archivist of the US (who leads the National Archives) had been sacked, without warning or justification. What many librarians had feared was now fact: great institutions were now a strategic target. My friend David Ferriero was Shogan’s predecessor. He had emailed me in June 2023 after the furore over Trump’s illegal hoarding of classified records in the guest bathroom at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida. “The future of democracy is at risk,” Ferriero wrote. How right he was. The deputy US archivist and other senior staff were “advised” to take retirement or they too would be fired. The power grab has continued, with members of the advisory committee on historic diplomatic documentation, a body overseeing the declassification of government records related to US foreign relations, removed from office.

I spoke with Shogan on the implications of her dismissal. “The laws governing the protection of records are premised upon the service of an archivist of the US who undertakes the position in a non-partisan capacity,” she said. “The archivist must have the courage and conviction to act independently, without partisan or political allegiance. If this independence is threatened or abolished, then the records which document our shared history are at risk, potentially subject to the transient whims of those in power.”

The head of the National Archives is now Marco Rubio, the secretary of state. As Jacques Derrida reminded us in Archive Fever (1995): “There is no political power without power over the archive.”

Earlier this year, I asked the librarian of Congress, Dr Carla Hayden, to speak at an event in Oxford; to my delight, she agreed. The Library of Congress is the US national library, also responsible for the Congressional Research Service. Imagine the British Library and the House of Commons library in one. A week before the event in March, she cancelled. The situation in Washington “was too tense”, she told me: she felt she must stay in the city. On 8 May came the news I had feared. Hayden had received a stark email from the White House: “Carla, on behalf of President Donald J Trump, I am writing to inform you that your position as librarian of Congress is terminated effective immediately.” At first, she thought it must be fake. No reasons were given, but they were later revealed as following the now-familiar pattern.

A report issued by the far-right organisation the American Accountability Foundation titled “Liberals of the Library: Political Bias Inside the Library of Congress” had accused her of exposing children to books on sexual identity, and revealed that she is a registered Democrat who had made modest donations to Democratic causes.

Hayden is a brilliant librarian. I have used the Library of Congress as a researcher many times, and I have seen how she strengthened it, by adding important collections, and opening it up to the whole of American society through digitisation, exhibitions and events. The Booker-winning US novelist George Saunders described Hayden as “energetic, engaged and utterly dedicated to the work of the library”.

Trump’s press secretary, Karoline Leavitt, attempted to justify her removal with a bogus claim: Hayden had been dismissed because the library had been providing “inappropriate books for children”. Basic research shows this to be nonsense: the minimum age to obtain a reader’s card is 16 and the library is not a conventional lending one. Its books arrive automatically under the “legal deposit” legislation.

Trump replaced Hayden at the Library of Congress with his Stormy Daniels lawyer

Trump replaced Hayden at the Library of Congress with his Stormy Daniels lawyer

Who did Trump replace this great librarian with? The deputy attorney general, Todd Blanche – the lawyer who defended him in a case brought by adult-film star Stormy Daniels.

The “Liberals of the Library” document also accused Shira Perlmutter, the head of the library’s copyright office, of being a Democratic party donor and “part of a leftwing family”, quoting comments made by her brother, the Nobel prize-winning scientist Saul Perlmutter, that the US was in a “dangerous era” after Trump’s victory. She was sacked on 10 May.

Perlmutter’s office had issued a report that stated training sets created for generative AI have, in some cases, infringed copyright. No one is shocked to learn that several of the tech bros hate the very idea of copyright. Jack Dorsey, one of the founders of Twitter, now X, is proposing to “delete all IP law”, a goal endorsed by Elon Musk. The big tech moguls all contributed funds for Trump’s inauguration. We now see what their donations may buy them.

Where has Congress been in all of this? It is called the Library of Congress for a reason: in 1800, Congress voted to raise funds to establish the library, and after it was burned down by the British in 1814, it voted to replace the destroyed collection. The governing legislation allows the president to nominate the librarian, but only “on the advice and consent” of the Senate.

The staff of the library have so far bravely refused entry to the individuals selected to replace Shira Perlmutter and other ejected senior staff until they are authorised by Congress. Will Congress assert its independence as a law-making body and defend against the president’s attempt to control its library? The Library of Congress is now a test case in the separation of powers within the US constitution.

The US war on libraries is being exported. It is useful to look at Ireland, a country with close cultural ties with the US and with a long history of censorship, to see how they have been able to face the battles. Catherine Gallagher is county librarian for Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown, whose DLR Lexicon is the largest public library in the country, with more than a million visits a year. She told me about the wave of pressure on public libraries to remove certain books from circulation, especially those on LGBTQ+ topics, such as Juno Dawson’s This Book Is Gay, one of the most contested.

Not only have there been campaigns to ban these books, but groups such as the Natural Women’s Council, following the American playbook, have claimed that librarians are sexual groomers and promoters of paedophilia. The Natural Women’s Council is led by Jana Lunden, an American now living in Ireland, who modelled the group on Moms for Liberty; it also claims to “protect childhood”. The Irish library system stood firm against these attacks, which have eased. Gallagher is clear as to why: “Library services in Ireland are free, open and democratic.”

In 2023, the UK’s professional body for librarians, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals, surveyed librarians to understand the degree of pressure to remove or censor library books. At the time, 82% of librarians identified an increase of pressure, especially relating to books with LGBTQ+ themes. Can British libraries stay out of the conflict?

Librarian Amanda Jones, who sleeps with a shotgun under her bed

One of the key messages from American librarians such as Louisiana’s Amanda Jones is to be prepared and to be organised. I have been working with colleagues from the UK’s library sector bodies, as well as national libraries, forming a group called the Libraries Alliance. Isobel Hunter, the chief executive of Libraries Connected, which supports public libraries, is one of my collaborators.

She set the UK’s situation in context: “Attempts to have books banned from public libraries remain rare in the UK,” she said. But public libraries are not, she is keen to emphasise, complacent: “With political debate increasingly polarised, it’s quite possible that libraries will find themselves caught up in divisive public battles. That’s why we must continually make the case for libraries as places of intellectual discovery and challenge, where anyone can explore new ideas and challenge old ones.”

As recently as August 2024, Spellow public library in Liverpool was subject to an arson attack by a mob angry that it had provided services to immigrant communities. A campaign raised more than £300,000 to restore the library within a few weeks. And earlier this month in Kent, a Reform UK councillor, Paul Webb, boasted on social media that he had ordered the removal of “trans-ideological material” from the children’s section of the county library service. In fact, there was no such material to remove.

One of the broader lessons from the US was highlighted to me by John Szabo, director of Los Angeles Public Library. Libraries were, until just a few years ago “a pristine brand”, he said. The war against them has begun to tarnish that brand. Libraries across the world must, he said, “have our fingers on the pulse of what they need most. And then align our services to support those needs.”

Libraries in the UK already do this well, but they have been hampered by decades of underfunding. While there are many examples of thriving public libraries in the UK, the picture is uneven. They need adequate funding for staffing, training and to replenish their book budgets. Proposals currently going through Glasgow city council will eliminate every secondary school librarian just to save £100,000.

On 10 May 1933, in the heart of Berlin, a mass book-burning was held, where texts considered to be “un-German” – including, of course, Jewish texts, but also books from a library of human sexuality on LGBTQ+ themes – were burned on a pyre on the Unter den Linden boulevard. It is tempting to draw the analogy between this event and the mass burning of books across the US right now.

But if we do we should also remember that new libraries were founded, such as the German Freedom Library in Paris, to counteract Nazi censorship. “You may burn my books and the books of the best minds in Europe,” Helen Keller wrote in 1933, “but the ideas those books contain have passed through millions of channels and will go on.”

We should, in this anniversary year, not only defend the bold and ambitious idea of the Victorian age – that society would benefit from its citizens having access to a free library – but ensure that all people can read freely. To do so, we must empower, support and celebrate the role of libraries and librarians as defenders of an open, pluralist society – the hidden but essential infrastructure of democracy itself.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Photographs by Nina Berman, Getty Images, New York Times