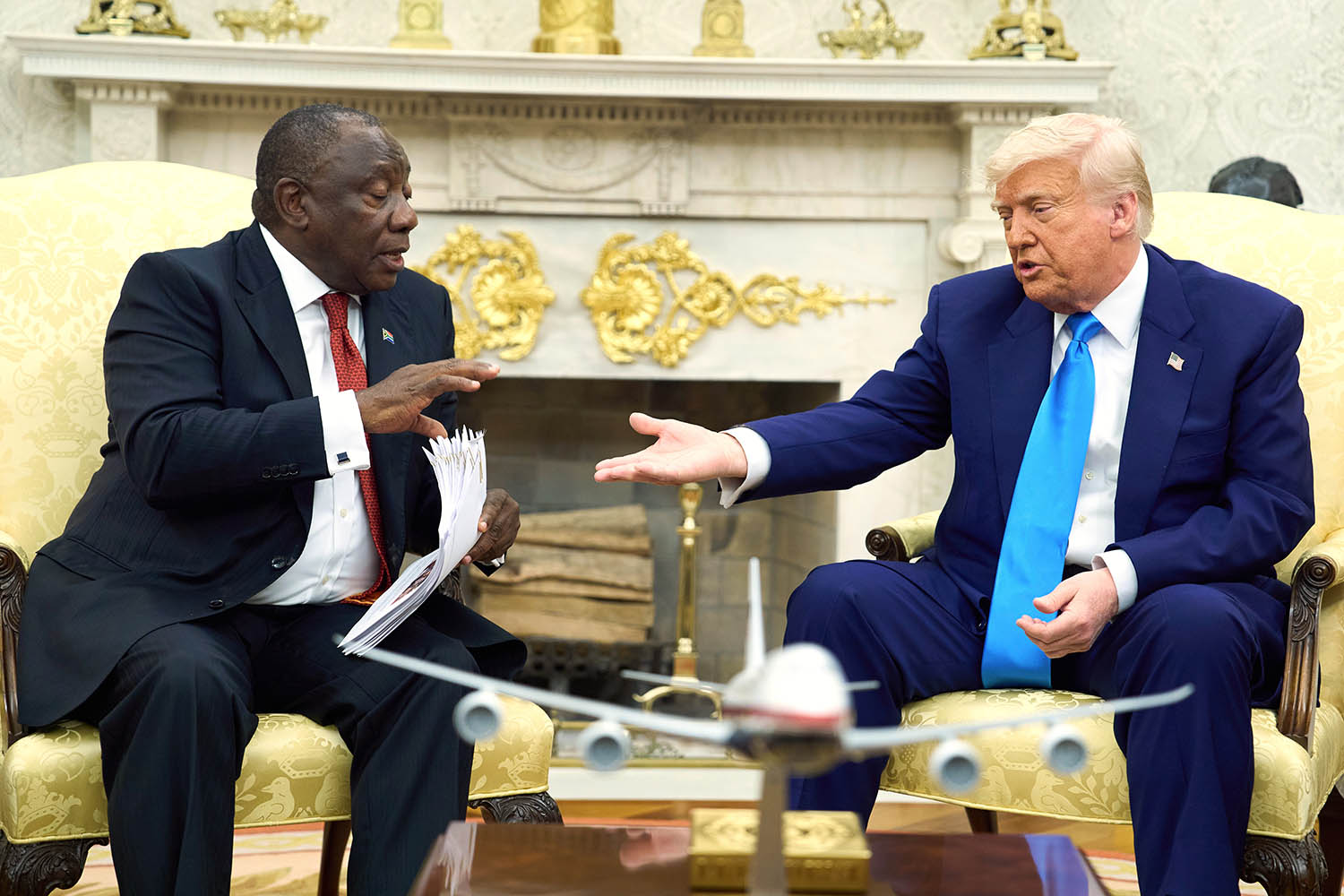

At around the same time last month as South African president Cyril Ramaphosa was arriving at the White House ahead of his Oval Office ambush, a Gulfstream V was on its way to South Sudan.

On board were eight migrants to the United States who were all being deported, but at least five of them had never set foot in Africa, let alone in South Sudan.

The flight tells us as much about Donald Trump’s transactional relationships with Africa as the embarrassing, fact-free reality show in the White House. In his first term, Trump dismissed Africa as being full of “shithole” countries, whose citizens should not be allowed into the US. His views do not appear to have changed. What’s different this time around is that he wants something from them.

These relationships are no longer about economic ties, development or values. They are all about extraction: what can America – or more precisely, Trump – get out of Africa?

From the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), he wants minerals; from countries like South Sudan and Rwanda he wants a place to send migrants; and from South Africa he wants a race-baiting storyline that appeals to his base.

Trump is not the only winner. As the investigative news outlet ProPublica revealed last month, the US government has been leaning on at least five African nations to buy into Elon Musk’s Starlink business. In one case, ProPublica reported that “senior State Department officials in both Washington and Gambia coordinated with Starlink executives to coax, lobby and browbeat at least seven Gambian government ministers to help Musk”. (Indeed, one of the lesser reported depressing moments in the Ramaphosa shakedown was the sight of the South African billionaire Johann Rupert pleading with the South African billionaire Elon Musk to provide access to Starlink for every police station in the country.)

State department insiders – career diplomats who have worked under both Republican and Democrat administrations – are despairing. Everything they used to have in their arsenal has gone: aid has been cut, soft power burned, anti-corruption initiatives shelved, support for independent media scrapped, promotion of human rights ended.

The Bureau of African Affairs in the state department currently has no permanent leader, while the man running Trump’s Africa operation is a businessman with no diplomatic experience who just so happens to be the father-in-law of the president’s daughter.

It would be wrong to suggest that there was some golden age of progressive and positive American influence in Africa. Throughout the cold war America backed dictators whom they saw as a bulwark against communism, whether that threat was real or imagined. In what’s now the DRC, the CIA helped kill Patrice Lumumba, the country’s popular independence leader, then installed the brutal Mobutu Sese Seko. In the 2000s, the threat of terrorism on the continent played a similar role as authoritarian regimes like Ethiopia’s benefited from US largesse that supposedly helped them quell al-Qaida-linked groups in neighbouring Somalia.

But over the past three decades, an element of US diplomacy has understood the need to stand up for democracy, human rights and development. George W Bush created the President’s emergency plan for Aids relief (Pepfar) that did more than any other global programme to eradicate HIV/Aids across Africa. All of this now appears to be gone.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Trump’s attitude is brutally transactional, but there is a danger for America that it loses more than it gains. In the years after the cold war, the US was the dominant international force in Africa. That is no longer the case. For more than two decades, China has invested billions across the continent, building roads and railways, schools and hospitals, parliament buildings and football stadiums. In return, it has gained access to markets, negotiated generous oil export deals and built up huge political and cultural influence.

In recent years Turkey, the United Arab Emirates and Russia have also extended their reach across the continent. None of these countries has any interest in promoting democracy or human rights, while their interests in economic development have more to do with their own bank balances than the growth rate in Kenya, Ethiopia or Burkina Faso. For Russia, the relationship is even more deadly – its Africa Corps troops have supported coups and provided military support to dictators. African governments that have traditionally turned to the US for support are already beginning to look elsewhere.

The repercussions for African citizens could be profound. African human rights groups have long relied on both financial and political support from western nations – without that, abortion rights and LGBT rights could be rolled back. Without external pressure for democracy, authoritarianism could rise across the continent.

There is not a country in the world that will be unaffected by the next four years of Trump. But in countries where the economy is weak, democracy is fragile and the rule of law is a work in progress, the consequences could be catastrophic.

Photograph Evan Vucci/AP