The US government is pouring millions of dollars into a deadly militarised initiative to distribute aid in Gaza without internal oversight, The Observer has found.

In the almost six weeks since a private aid operation called the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation (GHF) launched, the opaque effort to replace UN operations in Gaza, rather than work alongside them, has been at the centre of controversy. Israeli soldiers and armed American contractors have been accused of shooting at crowds of starving people surging towards their distribution centres. Hundreds have been killed and thousands wounded, according to medics and the UN.

While both governments initially disclosed little about the plan, The Observer has found that US government funds were given to the GHF without the standard internal review. This funding has been matched by allocations from the Israeli government, according to two US government sources.

In late June, the US state department announced it would give $30m (£22m) in funding to the GHF, despite a string of controversies since its launch a month earlier. One US government employee said they expected the state department to continue the funding, perhaps even monthly, adding that the $30m figure was provided by the GHF based on “its monthly operational needs”.

Two US government sources said the money provided by the state department was complemented by Israeli government funds.

The Israeli government has fiercely denied reports it has funded the GHF, and a spokesperson for the Israeli foreign ministry declined to answer questions about it. Despite these denials, two high-profile Israeli opposition politicians have accused their government of funding the project and the public broadcaster Kan reported last month that the Israeli defence ministry had covertly provided over $200m to the GHF.

The checks that normally accompany the state department funding are missing, according to one US government employee. Under normal circumstances, they said, “operational documents that detail everything about the project, including ownership, financials and operational details”, would be circulated among government departments prior to funding being disbursed. In the case of the GHF, the government agencies normally tasked with review have not seen any such documentation.

“Anything financial for the West Bank or Gaza is the most heavily scrutinised that we review, either directly or indirectly, but it wouldn’t surprise me if because Israel wants this or due to [GHF’s] connections, that review is ignored in this instance,” they said, adding that the lack of oversight is more in keeping with lax internal visibility over US government aid to Israel, rather than Gaza.

The state department declined to comment on the lack of oversight, outlining that it approved $30m in funding and calling “on other countries to also support the GHF in its critical work”. What becomes of the GHF if a ceasefire between Israel and Hamas is reached and the UN resumes its aid operations is uncertain. One US government source told The Observer that the financing is expected to last until the end of this month and what will happen after that is unclear.

Under the UN, aid – including items such as tents, soap and food – was distributed at 400 points across Gaza. The GHF replaced this system with just four distribution points after a total Israeli blockade began in March, pushing 2.2 million people to the brink of famine.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

The initiative distributes boxes of dry goods such as pasta and lentils at distribution centres situated between towering sand dunes, ringed by metal pens and gates, and guarded by armed American private contractors. In order to reach food, thousands sleep in the street among piles of rubble awaiting a notification that one of the sites is open for just a few minutes at a time, often in the middle of the night.

People, some carrying aid parcels, walk along the Salah al-Din road near the Nusseirat refugee camp in the central Gaza Strip.

There have been regular, at times daily, reports of hundreds of adults and children being shot trying to reach aid. The medical aid organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) called the initiative “slaughter masquerading as aid” and said last week that over 500 people have been killed and 4,000 wounded in its first month. The UN’s human rights office said it had recorded 613 deaths near the GHF’s distribution points and close to convoys in a one-month period until late June, adding there have been further incidents since.

While the GHF has repeatedly denied reports of violence at its sites, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) stationed at the perimeter said they fired on crowds who deviated from “designated access routes”, or fired warning shots. Reports from the Israeli media of soldiers told to fire at civilians have prompted internal investigations and changes to guidance given to troops, they say.

Aitor Zabalgogeazkoa, MSF’s emergency coordinator in Gaza, described an influx of over 500 patients in two small field hospitals they operate close to the GHF’s distribution centres. In recent weeks medics have treated hundreds for gunshot wounds, indicating direct fire rather than warning shots.

“All the deaths that we registered in the health centres had fatal injuries in the chest and abdominal areas,” Zabalgogeazkoa said. “These are not warning shots, they are shots directed at people.

“People are getting to the sites earlier than the distribution and they are getting shot. They get there when they are looking for food, and they are getting shot. If they leave late they are getting shot. It’s what patients tell us.”

News last week emerged that it may not be only the IDF that is doing the shooting. American contractors employed by two companies – UG Solutions and Safe Reach Solutions (SRS) – are also using live fire, according to accounts obtained by the Associated Press (AP). Contractors also hurled stun grenades and used pepper spray on crowds of Palestinians seeking aid, they said. The GHF denied AP’s reporting, claiming it originated from “a disgruntled former contractor who was terminated for misconduct weeks before this article was published”.

Reports indicate that SRS, a company registered in Wyoming late last year and headed by the former CIA staffer Phil Reilly, subcontracts to UG Solutions to recruit armed guards, who were seen at an Israeli military checkpoint during a previous ceasefire in Gaza.

Reilly also previously spent eight years working with the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and left around the same time that SRS was founded. Reporting from the Financial Times describes how Reilly’s relationship with BCG and another consultancy group, Orbis, meant that BCG was hired to consult on the GHF’s operations. As part of that work, BCG also considered the projected $5bn cost of moving hundreds of thousands of Palestinians out of Gaza by offering “relocation packages”.

The BCG said two high-level employees were fired after a team had carried out unauthorised work “to help establish an aid organisation intended to operate alongside other relief efforts to deliver humanitarian support to Gaza” last October.

Beyond reports of it offering logistical support to the GHF little is known about SRS. It was registered in Delaware early this year and it recently announced it was recruiting for a position intended to “facilitate dialogue and trust-building between security, logistics and humanitarian actors”, including the UN, despite humanitarians long refusing to work with the initiative.

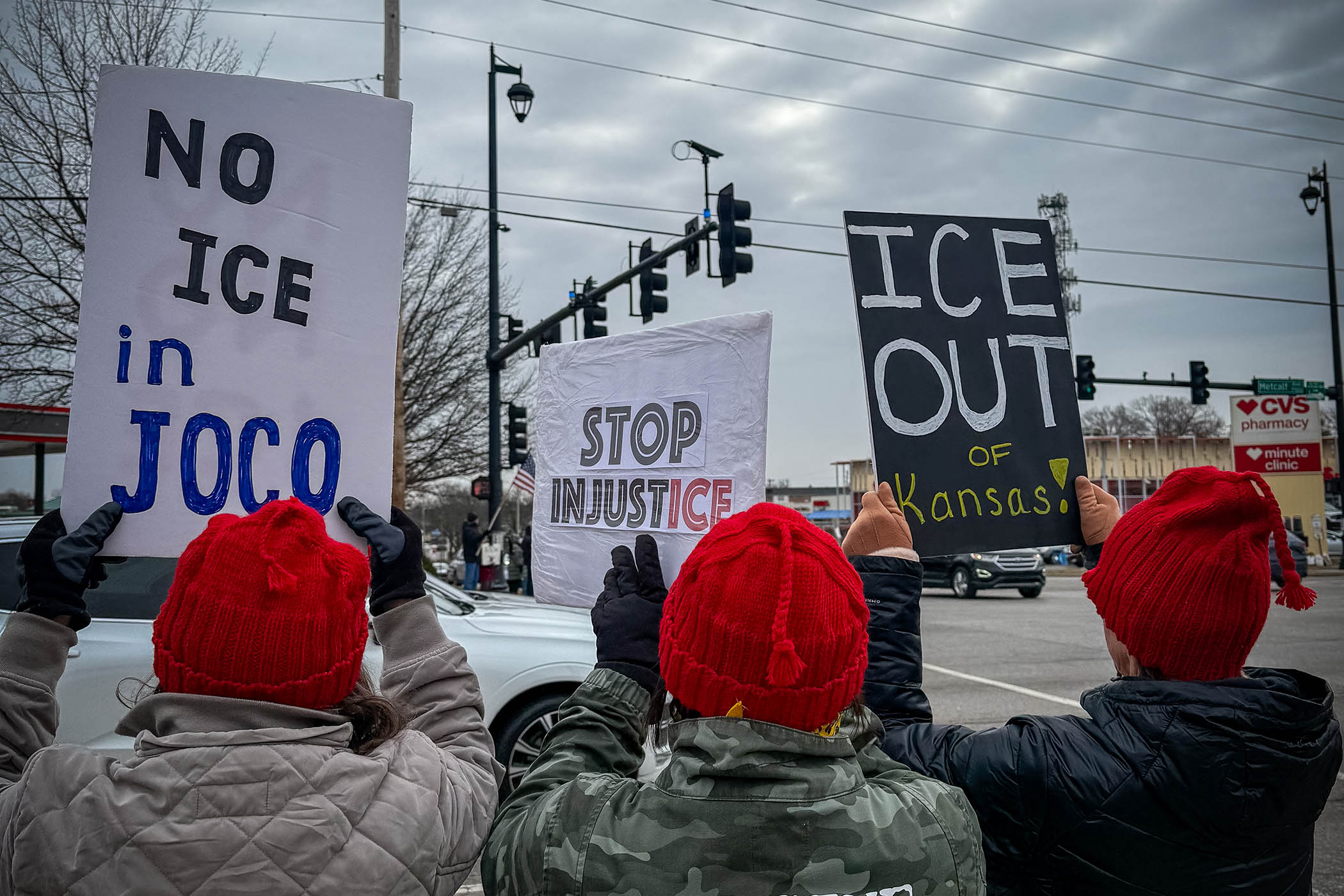

The lack of clarity about how each company is funded or their day-to-day cooperation has fuelled questions about use of US government funds. Chris Van Hollen, who serves on the Senate’s foreign relations committee, condemned the support for GHF.

“It’s downright shameful that the Trump administration is using American taxpayer dollars to fund this scheme to replace respected international aid organisations with this shadowy group of mercenaries who are complicit in killing starving people,” Van Hollen said.

Sam Rose, the acting director on Gaza for the UN’s agency for Palestinians, known as UNRWA, estimated that the GHF’s highly restricted distribution system could feed just a quarter of Gaza’s population each day at best. The initiative also ignores other needs essential for survival such as fuel, cut off by an Israeli blockade now endangering vital medical equipment in hospitals.

“We don’t know what that $30m is paying for: is it paying for international mercenaries?” Rose asked. “If it’s paying international staff salaries, that money will not go far at all. If it’s paying for food, I would guess it would cover less than a month’s worth of needs, but GHF doesn’t appear to have an ambition to feed the entire population.”

In a statement to The Observer, the GHF denied that any of the $30m provided by the US government will go to SRS, but declined to share any details about how it will be spent.

UNRWA appealed for $488m to feed half of Gaza’s population this year, a far larger sum. Humanitarians such as Rose understand that the GHF instead buys small quantities of surplus items or procures from Israeli markets, to supply a system they say is fuelling widespread starvation.

“It is criminal what we’re seeing with this distribution mechanism, it is in no way set up to meet the needs of the most vulnerable people killed on a daily basis trying to get the food they need, forced into a cattle pen in an active warzone,” said Rose.

“This shows they have no intention whatsoever to feed people. It appears to be a fig leaf to take pressure off the starvation, to undermine the UN and existing distribution mechanisms and to buy time so Israel can continue to prosecute its military objectives, whatever they may be.”

Private initiatives to get aid into Gaza are nothing new, but until the GHF most were intended to complement the UN, rather than replace it. Supplanting the range of services provided by the UN – which includes schooling, medical centres and many vital services beyond food – is a tough, if not impossible, proposition.

Israeli officials have long alleged supplies are diverted to Hamas, despite UN officials in Gaza and international aid groups denying there is any evidence to support this.

Max Rodenbeck of the International Crisis Group (ICG) called this a fundamental flaw in the GHF initiative. “It was supposedly created to get around this big problem, but that problem doesn’t exist.”

An ICG report described how the GHF is operating while all 2.2 million people in Gaza remain close to famine. “The world, it seems, is witnessing an experiment: an attempt to indefinitely maintain Gaza’s population below the famine threshold while turning food into a weapon of war,” it said.

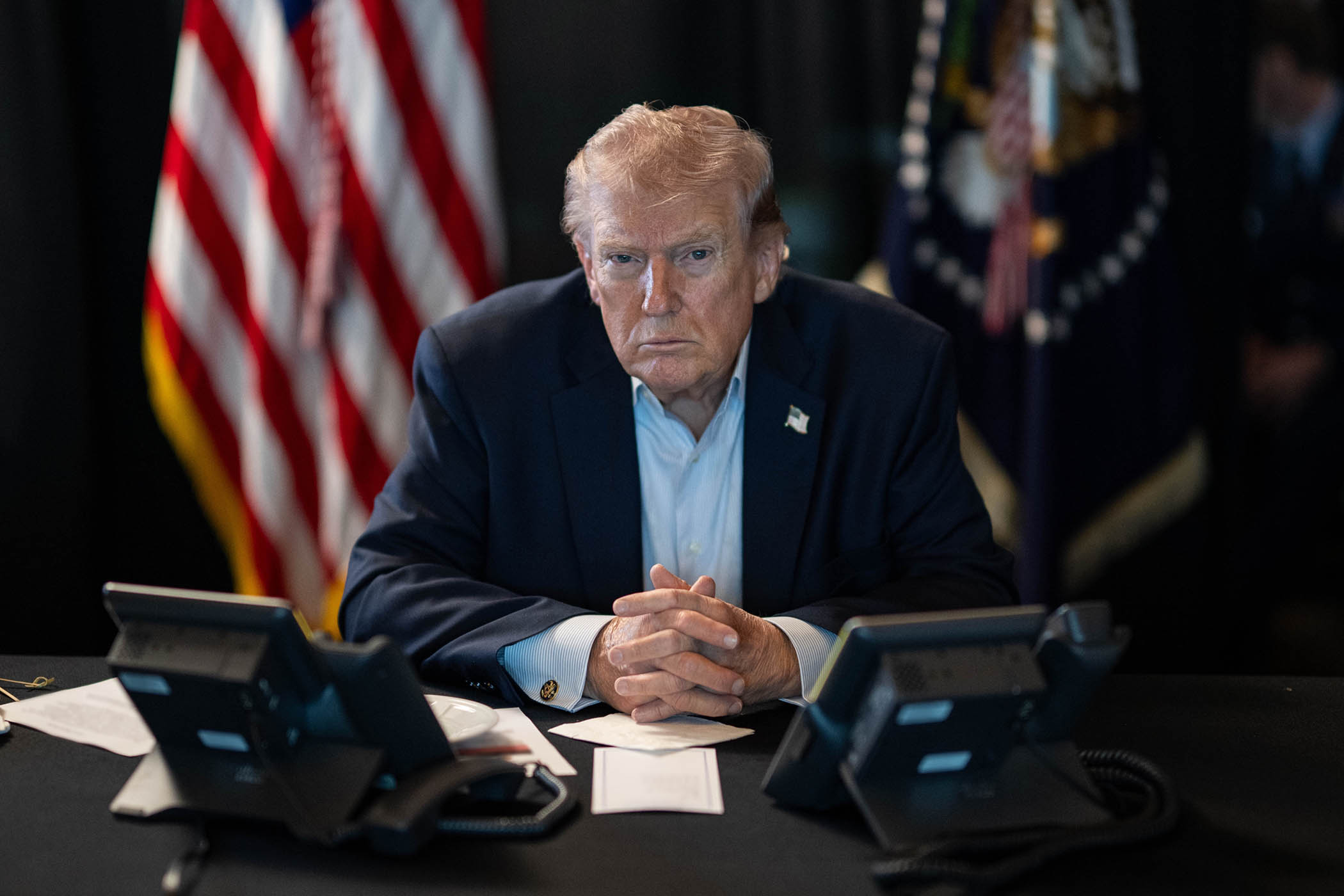

The Trump administration has doubled down on its support for the GHF, despite the hundreds killed while seeking aid.

The GHF’s chair, Johnnie Moore, an evangelical pastor with ties to the White House, has defended it in public but all the while a growing outcry has continued amid fears the initiative has done more to harm Gaza’s population than to help.

Photographs by Saeed M. M. T. Jaras/Anadolu via Getty Images, Eyad Baba/AFP via Getty Images, Guy Smallman/Getty Images