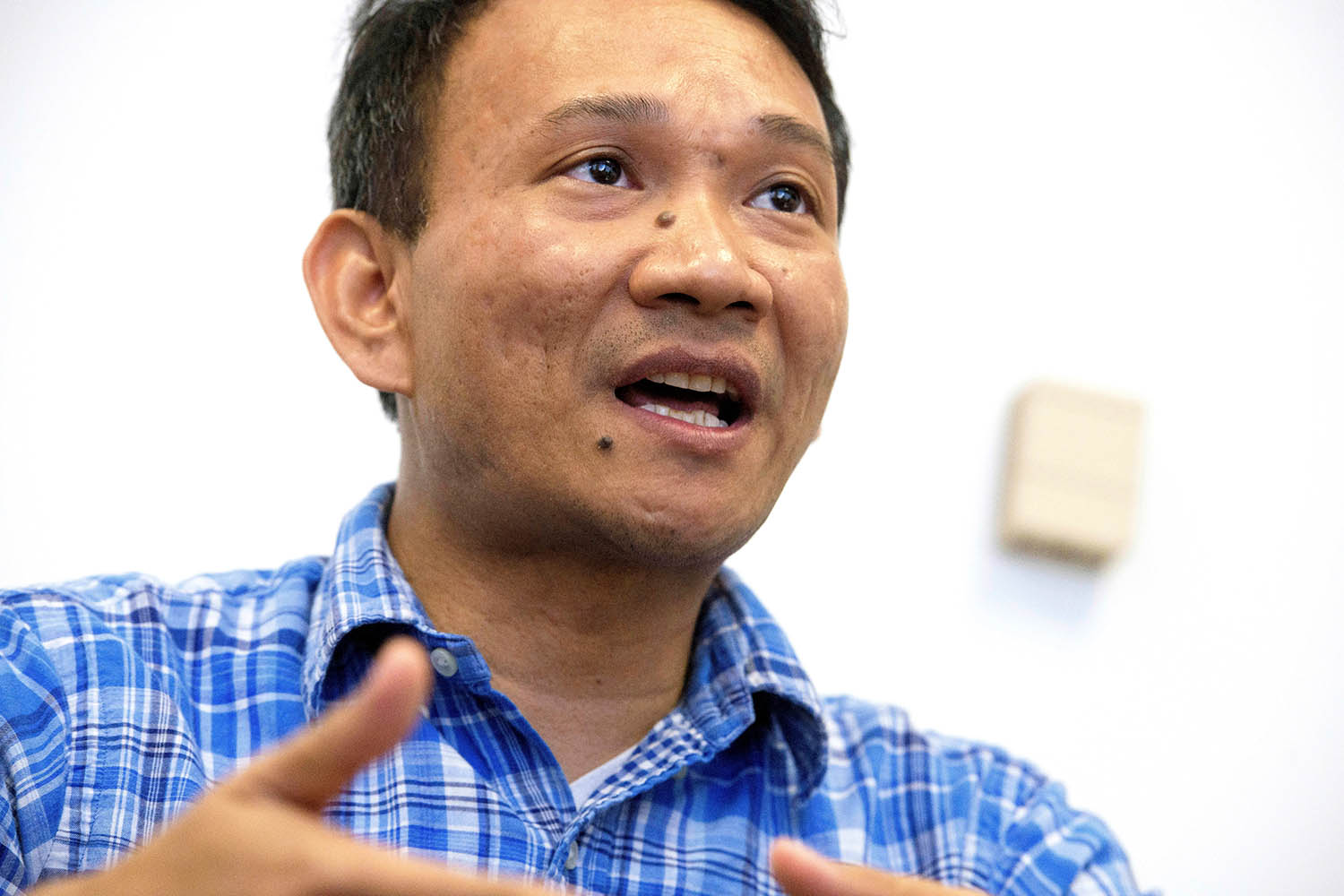

In 2017 Vuthy Tha left Cambodia by crossing into Thailand on foot. Two of his colleagues at Radio Free Asia (RFA), a non-profit news service funded by the US government, had been arrested. When plainclothes police came sniffing around his family home, asking for his whereabouts, he feared he would be next.

In the middle of the night Vuthy grabbed his laptop, dictaphone and passport and made his way to the border. For the next seven years he lived as a refugee in Bangkok and continued to work for RFA, covering crackdowns on opposition parties and concerns about election rigging back home in Cambodia.

Even in Thailand Vuthy did not feel safe. While he was there, several Cambodian journalists and activists were rounded up and sent back home. “I was constantly worried,” says Vuthy.

Last year his limbo finally came to an end when RFA, where he is now a video editor and news presenter, brought him to the US on an HB-1 visa, which allows organisations to hire employees in the US for speciality roles.

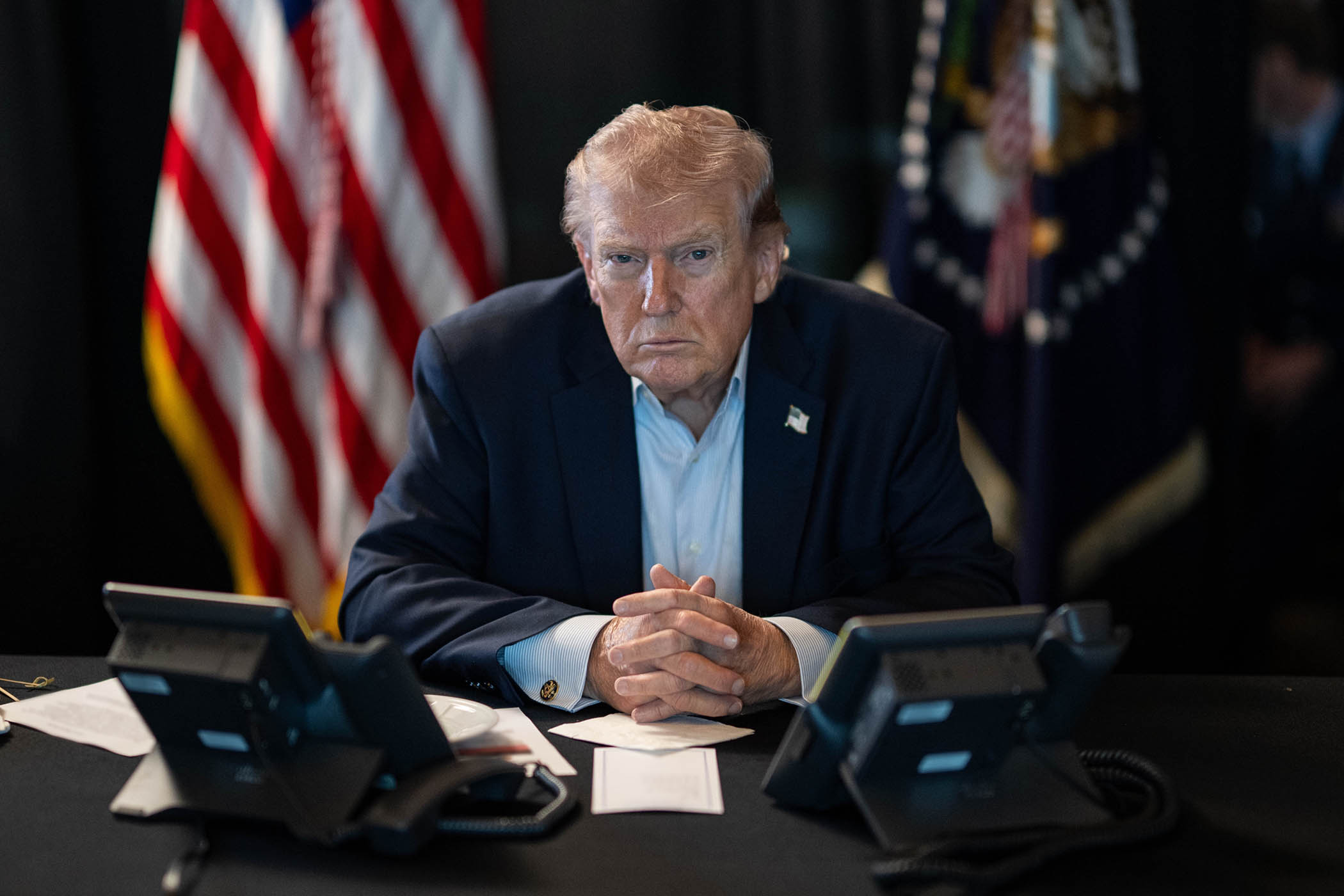

Now Vuthy’s life has again been thrown into uncertainty after Donald Trump signed an executive order gutting the US Agency for Global Media (USAGM), the federally funded service that runs Radio Free Asia, Voice of America (VOA) and several other outlets.

These outlets broadcast impartial, fact-based news in places where freedom of expression is severely curtailed, such as Eritrea, China, Russia and Myanmar. For decades they have been viewed by successive presidents as a key – and cost effective – way of promoting US interests and the gradual global spread of democracy.

However, the Trump administration has described the output of USAGM outlets as “anti-Trump” and “radical propaganda” funded by taxpayers. VOA has already laid off more than 500 contractors, and nearly all of its 800 staff have been on administrative leave since March. In May Radio Free Asia fired 90% of its 280 US-based staff because, it says, it could not afford to keep them.

Several lawsuits have been launched to protect the outlet’s funding. One case, filed in New York in March by VOA employees, the rights group Reporters sans Frontières and others, alleges the Trump administration’s actions violate a law protecting the “professional independence and integrity” of VOA and other USAGM outlets.

It also warns their dismantling has created a vacuum that is “being filled by propagandists whose messages will monopolise global airwaves”. This process is well under way. In February, Russia’s Sputnik news service opened an Africa service based in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. The state-owned China Global Television Network (CGTN) is also pouring resources into expansion across the continent.

The US outlets’ defenders say that in an era of mass misinformation and creeping authoritarianism, the future of independent journalism is at risk. “In most of the places where we operate, we are the last standing media organisation broadcasting in the local language and countering the official narrative,” says Tamara Bralo, RFA’s head of journalist safety.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Caught in the middle are journalists like Vuthy, who fear losing their immigration status in the US and being sent home to face persecution. So far, no RFA journalists have been deported, but they have received no guarantees about their future.

For now Vuthy and others have been kept on as part of a skeleton crew, a move designed to protect them for as long as possible, says Poly Sam, the director of RFA’s Khmer language service.

“If I go back to Cambodia I will be arrested, for sure – maybe even killed,” says Vuthy, a single father of two. He says he is grateful to the US for funding the work of RFA and bringing him to Washington: “In the US I am happy, I am safe. I can fulfil my dream for my kids, live a normal life… Without RFA I would have ended up somewhere in jail.”

It is a real possibility. Four RFA journalists are behind bars in Vietnam and another is held in Myanmar, says Bralo. They include the Vietnamese journalist Pham Chi Dung, who was handed a 15-year sentence in 2021.

In total, 11 reporters for USAGM outlets are imprisoned around the world, according to an open letter sent on 1 April to the Senate committee on foreign relations by PEN America, the Committee to Protect Journalists and 35 other rights groups.

The organisations said at least 23 USAGM journalists could be sent back to their home countries if their US work visas are cancelled and risk “being immediately arrested upon arrival” over their reporting. They identified a further 84 who could face “other adverse consequences”.

The list includes a journalist at a VOA service in the Pacific region, who asked The Observer not to print his name or home country, so great are his fears of reprisals. He has lived in the US for a decade on a J-1 visa and is still waiting for a green card.

“It’s very unfair,” the journalist says. “The US is my home. I’ve worked here, studied here and paid tax. I have contributed to serving US interests, and now they throw me away like a piece of trash.”

Photograph by Rod Lamkey, Jr/AP