In early 1969, not long after the strikes and civil unrest that had rocked Paris, Charles de Gaulle felt his countrymen were not ready to hear about the moral ambiguity of life under Nazi occupation. “France doesn’t need unpleasant truths,” the president said when told about a TV documentary. “France needs hope.” The programme was axed.

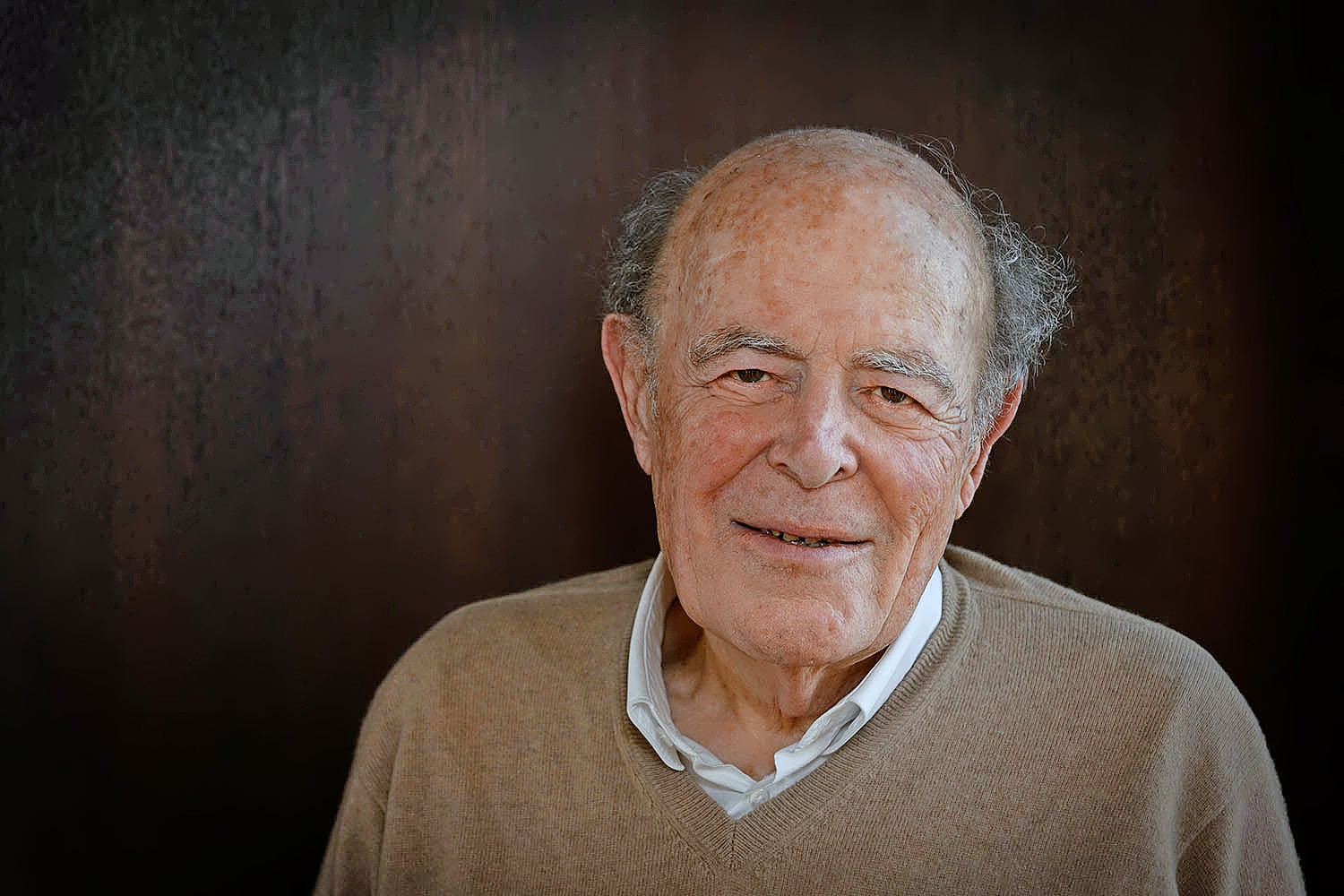

Marcel Ophuls, who had been commissioned by French state TV to make the two-part film about collaboration, acknowledged the president’s sentiment. “It’s rather beautiful,” he said. “But his job and mine were not the same, were they?”

The son of a German-Jewish film-maker, whose family had fled to France with the rise of Hitler and then again to America after their adopted land fell, Ophuls did not intend to condemn those who failed to resist the Nazis. But The Sorrow and the Pity revealed something uncomfortable behind De Gaulle’s national myth. War had been messy.

Ophuls spent two years on his film, much of it interviewing people in Clermont-Ferrand, a city in the Auvergne. Some admitted they collaborated out of antisemitism, others simply for a quiet life. One son of an aristocrat asked what else someone of his class could have done. “I couldn’t be a communist, obviously,” he said. “Besides, we were all a little thrilled by Hitler’s show. It was like Cecil B DeMille.”

The commander of the Nazi forces in the city proudly wore his medals for the interview and complained the Resistance didn’t play fair: they should have worn a uniform so he could spot them. A gay British agent for the Special Operations Executive spoke of sleeping with the enemy.

There were tonally off moments, such as when Pierre Mendès-France, prime minister in the mid-1950s, described his escape from prison. He was poised to jump from the wall when he saw a couple in the bushes. “He knew what he wanted, she was unsure,” he said. “Her indecision was very inconvenient for me.”

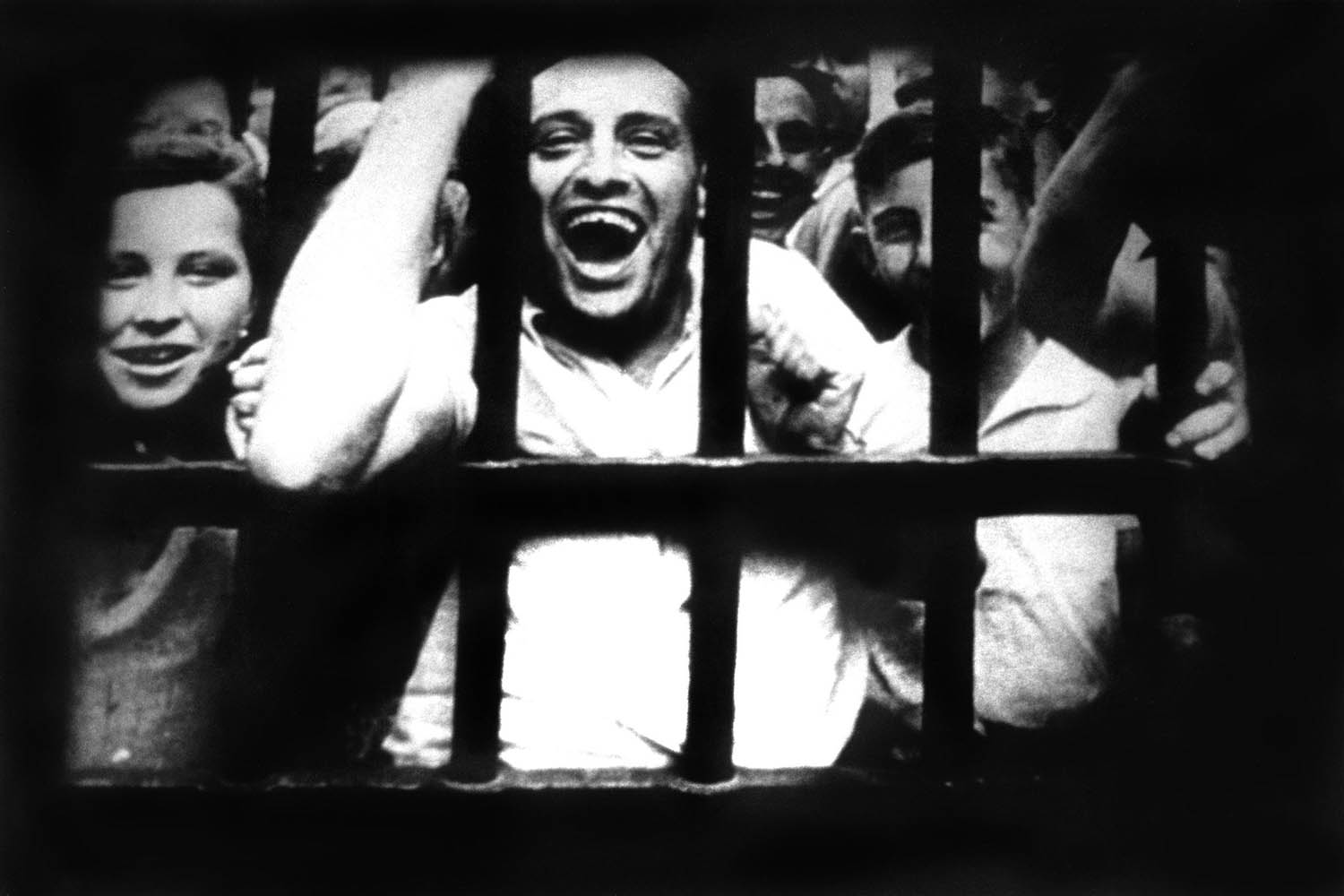

A still from The Sorrow and the Pity, 1944

Who knows how any of us would react in the crisis of enemy invasion? Far from being critical, Ophuls’s message was summed up best in the film by Anthony Eden, the British wartime foreign secretary: “One who has not suffered the horrors of an occupying power has no right to judge a nation that has.”

It was too much of a risk for the French TV network, which refused to show it until 1981. Instead, Ophuls released it as a 251-minute cinema feature. This led to it being nominated for an Oscar, winning a Bafta and appearing as a joke in a Woody Allen film. “I’m not in the mood to see a four-hour documentary on Nazis,” Annie Hall protests when Allen’s Alvy suggests they see it. Alvy later praises the Resistance’s bravery for listening to so much Maurice Chevalier. Allen had promised Ophuls he would treat his film with respect and admiration. “Never mind that,” he wrote back. “Just make it funny.”

Related articles:

The 251-minute cinema feature was nominated for an Oscar, won a Bafta and appeared as a joke in a Woody Allen film

The 251-minute cinema feature was nominated for an Oscar, won a Bafta and appeared as a joke in a Woody Allen film

Ophuls was born in Frankfurt in 1927; his family moved to France six years later and then to California in 1941. His father, Max, was a respected film director who dropped the umlaut on the U in their name on leaving Germany. They returned to Paris in 1950, where Marcel worked on John Huston’s film Moulin Rouge. In 1956, he married Regine Ackermann, who had been in the Hitler Youth, but Ophuls said that he didn’t “believe in collective guilt”.

In 1962, Ophuls directed part of an episodic film called Love at Twenty and then took the helm for the Jeanne Moreau comedy Banana Peel. He then moved into documentaries and after the success of one on the Munich crisis of 1938 was commissioned to make The Sorrow and the Pity. Sacked by the French network for supporting strikes in 1968, Ophuls completed it with German and Swiss backing.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

He would become used to sponsors getting cold feet. In 1972 the BBC commissioned A Sense of Loss about The Troubles in Northern Ireland but the broadcaster decided not to air it, feeling it was too pro-Irish, and the film had its premiere in New York. There was similar disquiet in 1976 over the length and focus of The Memory of Justice, a comparison of US policy in Vietnam and the Nuremberg trials.

A further Nazi theme was explored in his 1988 film Hotel Terminus about Klaus Barbie, the Gestapo officer known as the Butcher of Lyon for his atrocities and allowed to escape to Bolivia with the help of US counterintelligence. There were protests at its premiere at Cannes but it won an Oscar. Ophuls spent his last decade raising funds for an unfinished film, provisionally called Unpleasant Truths, on the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories.

Ophuls’s films were notoriously long. He liked to film fast, building up hours of material from which to select in the editing process. “That is the only creative part of it, the other thing is just gathering,” he said. “A bee goes from one flower to the other but the honey isn’t made while the bee is flying.”

For all his success, he called himself “a reluctant documentarian” and said he would rather have made feature films. “All of that is so much richer and more fun,” he said. “Instead of visiting old Nazis, you can work with Juliette Binoche.”

Marcel Ophuls, documentary-maker, born 1 November 1927, died 24 May 2025, aged 97

Photography by Everett Collection/Alamy