How shocking are the allegations that Raynor Winn may have twisted the truth in her bestselling memoir, presenting as fact what appears to be an extremely partial version of events?

For me, as a book publishing insider of more than 30 years, not very. A quick tour of the last couple of years in the book trade reveals many similar examples: self-confessed serial plagiarist Johann Hari’s most recent book, Magic Pill, contained inaccurate claims that had to be corrected post-publication; Boris Johnson’s hyped political memoir, Unleashed, boasted a string of errors (including, unforgivably, the number of victims of the 7/7 bombings); and Steven Bartlett, a podcaster exposed by the BBC as regularly platforming health misinformation, has been gifted his own imprint at Penguin Random House.

Winn, in a long statement on her website, has now offered her rebuttal of The Observer’s investigation, stating that The Salt Path is “not about every event or moment in our lives, but rather about a capsule of time when our lives moved from a place of complete despair to a place of hope”.

The fact is that publishing has a fact-checking problem, as demonstrated by the scandalously steady stream of non-fiction books subsequently debunked as containing outright falsehoods, spreading misinformation or presenting an unsubstantiated interpretation of historical events.

When I asked a senior executive at one publishing house to comment for this piece they jokingly replied: “There but for the grace, etc.”

Call me idealistic, but I worked at Penguin Random House for 28 years because I believed in its founder Allen Lane’s original mission to bring quality information to a mass audience. That vision is now under threat from publishing processes that put profit before truth. We’ve reached a critical cultural inflection point where information integrity is being systematically degraded.

Historically, publishers have been trusted by the public to promote fact-based accounts of our shared reality. Each sorry incident, such as the one exposed by The Observer last Sunday, frays that trust, and the consequences, as we have already seen from the great social media experiment, will be perilous for our democracy.

It’s time for the industry to wake up to the issues. Before I left Penguin Random House at the start of the year to join an organisation that works to combat misinformation, I wrote a piece for publishing’s house magazine, the Bookseller, calling for more rigorous in-house processes.

Unlike in journalism where fact-checking before publication is the norm, book publishing contracts place the onus on the author to verify facts. Individual editors may pay more or less attention to the process of verification depending on their training and inclination. I certainly worked with some extremely diligent professionals in my time at Penguin Random House.

However, shunting a book deemed to have sales potential into the market as quickly as possible was often the priority, particularly when it was surfing a lucrative reading trend. Let’s remember that The Salt Path spawned two bestselling sequels in quick succession.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Non-fiction book sales have been on a downward trajectory for some years as readers migrate to podcasts and other online sources of information. Traditional genres such as science and historical biography have contracted in favour of what publishers call “narrative non-fiction”. These books, often fast-paced retellings of historical events, combine factual research with descriptive storytelling that may verge on artistic licence. “Inspirational” memoirs such as The Salt Path and “wellness” manuals (often fronted by a social media influencer or celebrity rather than an expert) are two other genres favoured by commissioning editors.

In an increasingly online culture, where the habit of reading books is declining among the general public, publishing will jump on any trend that is showing signs of commercial life. But this production line approach to publishing comes with drawbacks.

The Bookseller followed up my piece with an investigation into industry practices that made for alarming reading. Anonymous insiders spoke of a culture where crushing workloads contributed to slapdash editing, with one editor commenting: “Corners are being cut and, unfortunately, fact-checking is one of those things that a lot of editors see as a ‘nice to have, but let’s cut it from the schedule if we don’t have time’.”

Publishers will go to great lengths to avoid difficult conversations with authors

Publishers will go to great lengths to avoid difficult conversations with authors

Amelia Fairney

This certainly chimes with my own experience at Penguin Random House, where editors were explicitly tasked with publishing more books every year, leading to an unmanageable title count incompatible with a thorough verification of authors’ facts and sources. Over the course of my career I sat through hundreds of publishers’ acquisition meetings where the commercial potential of each project was forensically analysed. I can only remember a handful of times when fact-checking was mooted – and then, only in the context of avoiding legal challenges.

Another complication, also present in the Bookseller’s survey of professionals, is publishers’ deference to authors, particularly those in whom they have most significantly invested. In my experience, publishers will go to great lengths to avoid difficult conversations with authors.

I witnessed this first hand at Penguin Random House a couple of years ago when Wifedom, prize-winning author Anna Funder’s acclaimed biography of Eileen Orwell, faced public criticism from experts over historical inaccuracies.

Although the publisher and the author eventually agreed to correct these in future editions, the in-house concerns I observed were first and foremost to defend and protect the reputation of a valuable author. In such an atmosphere, to raise any qualms about the authenticity of an author of the hugely money-spinning status of Raynor Winn would require some chutzpah.

In an age when truth is being undermined in the media and politics, I hope the many sad social media testimonies from disappointed readers of The Salt Path might finally catalyse some change. The harms of publishing as fact what is later revealed to be part-fact or even fiction are considerable – extending far beyond the financial consequences for publishers of disgruntled buyers demanding refunds.

As our information environment becomes swamped by a tsunami of misinformation, unverified claims and falsehoods, should book publishers be contributing to this flood or taking up the challenge to stem it? As Penguin Books celebrates its 90th birthday as a much-loved and respected feature of our national cultural landscape, I ask myself: What would Allen Lane do?

Amelia Fairney is head of strategy and communications at Shout Out UK, an organisation that promotes political and media literacy and works to combat misinformation. Previously, she was the Communications Director of Penguin General Books.

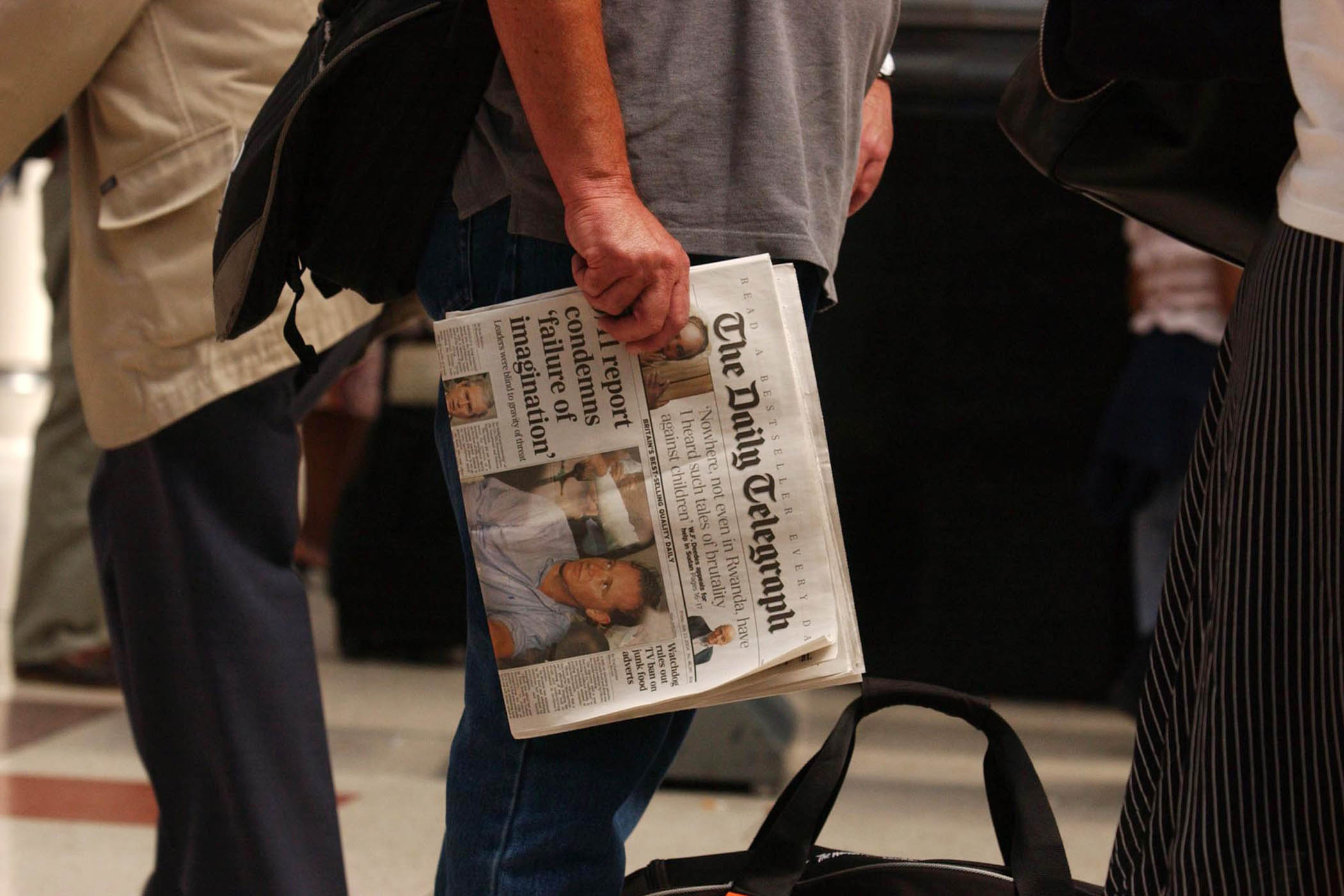

Photograph by Karen Robinson/The Observer