If they call me, I will not come. The meaning of this is not lost on members of the British Medical Association in England, 50.2% of whom did not vote to strike in the latest ballot on industrial action. The result reflects a rift in the profession, not a mandate to halt work.

As a resident (formerly junior) doctor in London, I grow wary of the tendency of the BMA resident doctors committee to call for strikes no matter the question. My concern chimes with the ballot results: those with misgivings were more likely not to return their slip than vote no.

The BMA believes doctors’ pay should be restored to its real-term equivalent of 2008. After 11 rounds of strikes, the union accepted a 22% pay rise last September. This means I can save a few hundred pounds a month, while before I struggled to get to the end of the month, never mind putting anything by. The union demands a further 29% raise using the retail price index (RPI), which accentuates inflation compared with the consumer prices index (CPI), a more common measure. The BMA’s chair, Tom Dolphin, says the raise would cost less than 0.5% of the NHS budget once money is returned through taxation.

The BMA’s central claim is that a doctor is not worth less than they were 17 years ago, so giving an inch on full pay restoration is unacceptable. The trouble is that now is not then. We’ve seen a financial crisis, Brexit, a pandemic, war in Europe, a self-injurious mini-budget, bounding inflation and US tariffs. None of this is the fault of NHS workers, but when you are part of a community, it is sometimes necessary to cede certain desires in the interest of the whole.

Public support for doctors’ strikes has fallen from 52% a year ago to 26% today. By and large, my patients believe I got a bigger raise than any other public sector worker last year and now expect me to get on with the job. The extent to which my colleagues are swayed by this varies.

My parents were GPs in West Fife and I was raised on an odd mixture of noblesse oblige and traditional working-class values (my mother descended from Yorkshire miners). I like being an NHS doctor because it entails decent human work and furthers a social ideal. I have felt cared about and respected by patients and colleagues in Edinburgh, Melrose, Orkney, Inverness and London.

My patients think I got a big rise last year and now expect me to get on with the job

My patients think I got a big rise last year and now expect me to get on with the job

I have been lucky. Many friends describe pay erosion as but one problem alongside growing job insecurity, relentless workloads, unrealistic expectations and repulsive treatment from their own patients – up to and including serious physical violence.

If your child wanted to become a doctor, would you find it reasonable that they might afford a home and ski trip once a year? Well, I am 33, and my holiday money covers the train fare to Aberdeen.

Related articles:

Loss is always painful. Most doctors hail from comfortable families. They feel what Thomas Hobbes knew, that “felicity … consisteth not in having prospered, but in prospering”. They sense, too, that it consists in how one fares in relation to one’s peers. Watching schoolmates skim the cream in finance and corporate law and management consulting tends to cloy. Who is to say what’s fair? I do not believe society owes me a flat in Belgravia. But I would like the health service to work, and to live in a country where we meet others halfway.

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

Doctors should be of their communities. The BMA should get past its zero-sum, knife-to-throat relationship with the health secretary. The government should agree to pay restoration on the basis of CPI inflation and couple this with student loan relief for doctors who stay in the NHS for six years after graduation. Achieving fairness in this more affordable way may help staunch the more than £200,000 public investment lost each time a UK-trained doctor boards a one-way flight to Melbourne.

Meanwhile, we can recruit motivated doctors to teams in which they can thrive and have them fret less about whether they’ll have a post next year. This is a better prospect for NHS improvement than all the private-sector waiting list initiatives and non-medical prescribers combined.

The price we pay for a thing reflects its value to us. The government should improve its pay offer, the BMA should flex on a demand the country no longer considers reasonable, and I should go to my night shifts next weekend.

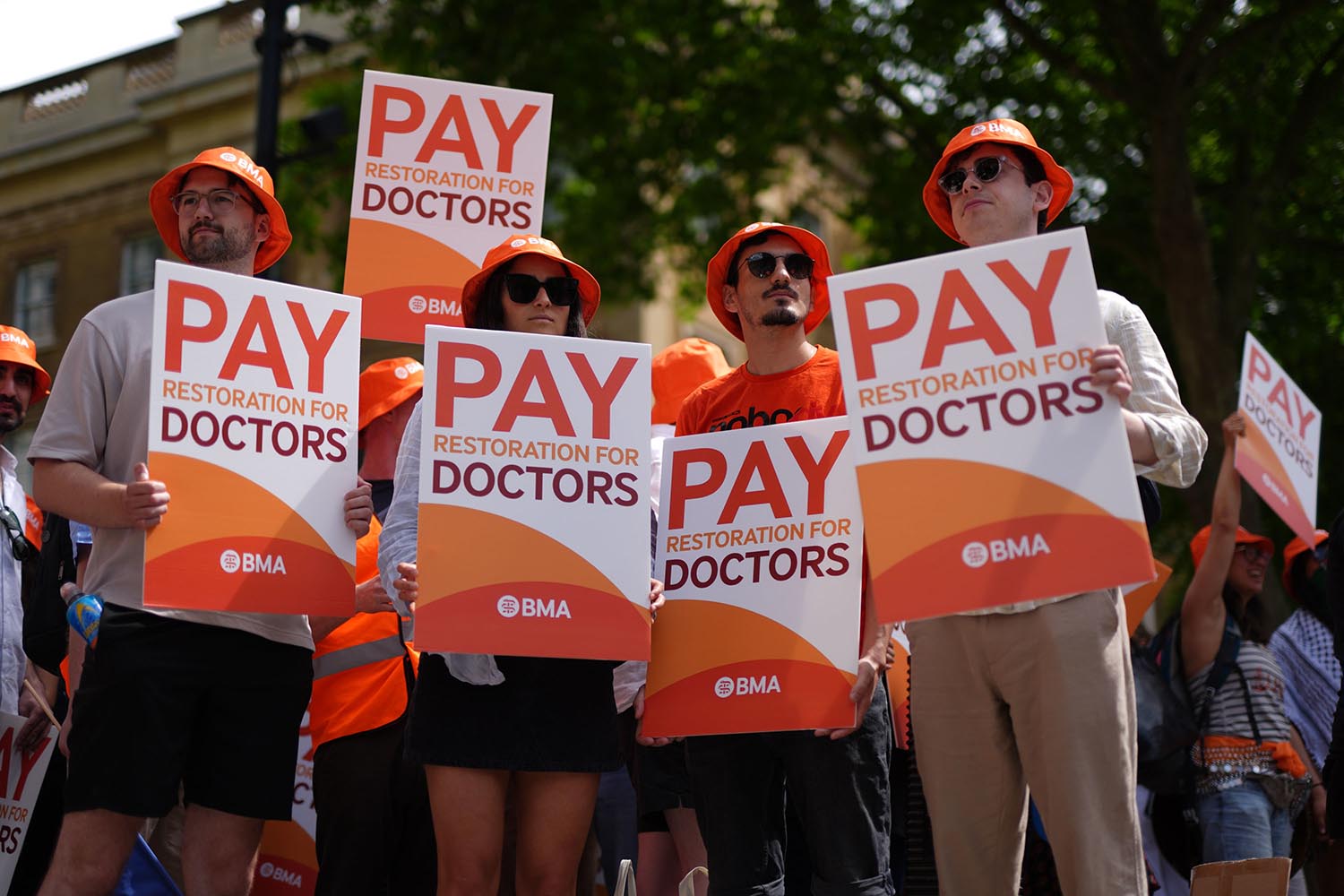

Photographs by Jordan Pettitt/PA Wire and OSA