What do we mean when we talk about conspiracy theories? It isn’t simply about holding the idea that there are sinister, secret forces doing shady things. From to Edward Snowden’s revelations about the NSA’s Prism phone-hacking programme to cover-ups of dossiers that led to the Iraq war, it is not in itself wrong to believe in the possibility that those in power are not on the level.

But as of 2017, more than half of Americans believe there was a second gunman in the Kennedy assassination. More than a third think global warming is a hoax. And as of 2021, 30% believe Covid was purposely created and 10% that the moon landing was faked – almost twice as many as in 1995, according to a 2022 paper in the journal PLOS One.

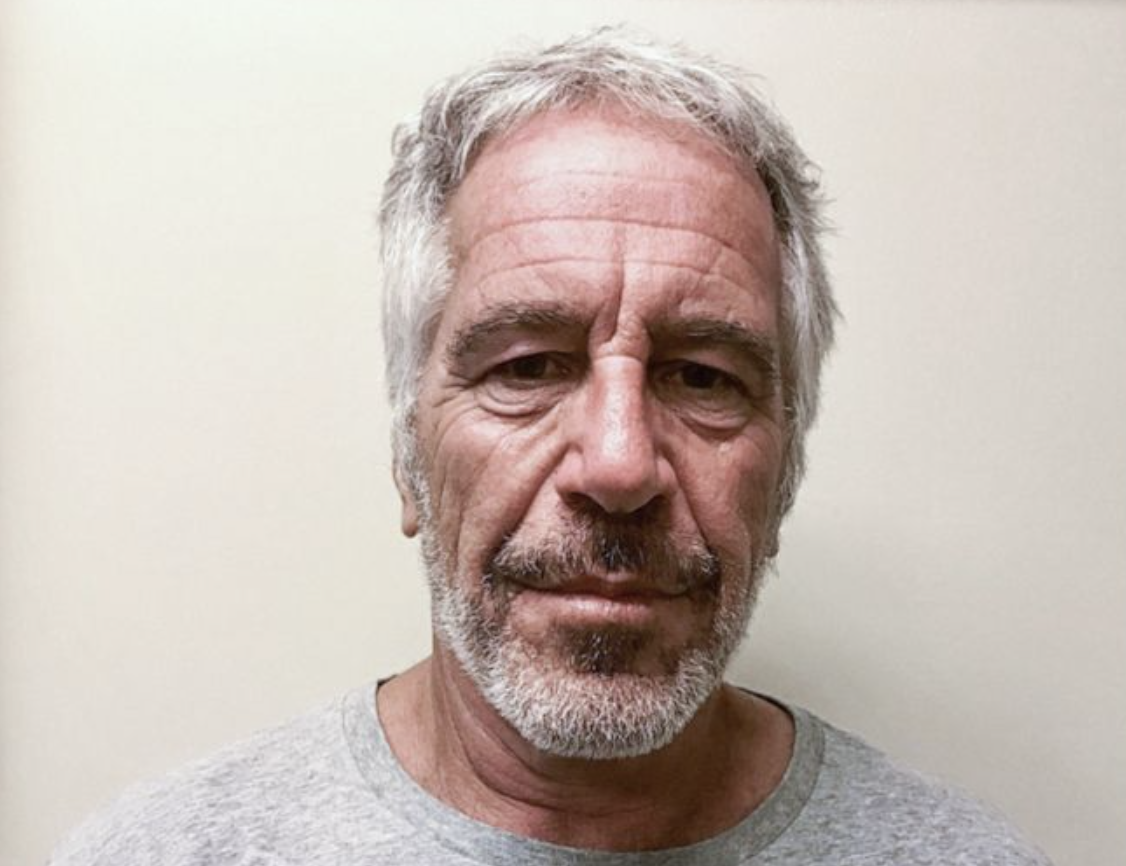

This kind of conspiracyism isn’t a facts problem. As the Epstein story rollercoaster shows, it’s a network effect problem: the story takes on a life of its own, and then it is often in someone’s interests to control it, for political or financial gain. Stories have power, and that is often an attractive proposition to harness.

Conspiratorial thinking becomes sick when it stops being a sceptical interaction with individual ideas and turns into an all-consuming mindset. A belief system – almost a religion. Once someone has fallen down the rabbit hole, everything becomes evidence confirming that belief system, especially in a social-media environment designed to create algorithmic rabbit holes and play to confirmation biases. Conspiracyism results when everything you see becomes fuel for an all-consuming worldview.

QAnon’s core belief is that the world is controlled by a cabal of sex-trafficking paedophiles: the thorny problem with the Epstein case is that there was indeed an elite paedophile ring

QAnon’s core belief is that the world is controlled by a cabal of sex-trafficking paedophiles: the thorny problem with the Epstein case is that there was indeed an elite paedophile ring

As a reporter, I spent years investigating conspiracy theories, especially the widespread ecosystem known as QAnon, and I saw this play out consistently. Every piece of information was, to the believer, evidence in favour: even contradictory evidence, because that’s what they want you to think. QAnon’s core belief is that the world is controlled by a cabal of sex-trafficking paedophiles: the thorny problem with the Epstein case is that there was indeed an elite paedophile ring.

But the conspiracy theory itself, just as in the case of QAnon, is secondary to the adaptability of the worldview to incorporate every new piece of information, to keep people within its closed paranoiac loop. This can often be entirely organic: once someone has fallen into this ecosystem, getting out can be extremely difficult, and belief in one conspiracy theory massively increases the likelihood of believing others too.

Evolutionarily, the brain is wired to find patterns in the world around it in order to understand and survive. A 2017 study in the European Journal of Social Psychology found that conspiracy-theory believers were more likely to find patterns in abstract artworks; another, in the journal Heliyon, found that conspiracy theory belief was related to physical differences in parts of the brain associated with categorisation of stimuli.

Related articles:

When someone falls into a conspiracy rabbit hole, it is because that instinct towards pattern recognition gets hijacked. Sometimes, there is an active effort to promote this phenomenon. In QAnon, a community of grifters sprang up to take advantage of those who had fallen under its spell.

Credulity has always led to profit for those selling nonsense theories. In 1930s Germany, the widespread conspiracy ecosystem framing Jews as a sinister cabal controlling the world is what made the Holocaust possible. The Nazis saw an easy way to harness a scapegoat for their own gain, and it helped propel them to power. (These tropes, of course, persist to this day.)

Newsletters

Choose the newsletters you want to receive

View more

For information about how The Observer protects your data, read our Privacy Policy

But sometimes, radicalisation can happen entirely organically, especially in an age when the internet has turbocharged the pathways for misinformation to travel. Conspiracy theoryism can spread exponentially across platforms such as Facebook, and AI will probably make it even easier for people to be sucked into these closed loop systems. Nothing distinguishes truth from fiction, so fact-checking becomes weightless.

Over and over, people I spoke to who had fallen into QAnon started with a sense of powerlessness over their lives. The pandemic added to one of the most powerful drivers of conspiracyism: fear. The conspiracy worldview provides a kind of safety: an overarching explanation that the fear is valid; that there is someone to blame. Framing the world in terms of “us” and an evil “them” is comforting.

It feels safer that way than the truth: that the world is a chaotic place, that people like Epstein can operate with seeming impunity not because they are part of a world-ruling cabal but because the sense of order, the explanation for life that people crave, simply doesn’t exist.

That, ultimately, terrifies people more than any conspiracy.

Nicky Woolf was the reporter of Finding Q: My Journey into QAnon

Photo by NASA/Liaison